| ESPN.com: Page3 |

Page 3 will examine the connection between sports and music all summer long. Also, catch SportsCenter's music series all this week at 6 p.m. ET on ESPN. Coming up: |

| |

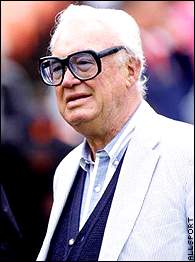

| Not even Harry Caray on his worst days butchered "Take Me Out to the Ballgame" as badly as Ozzy Osbourne did. |

| |

| No, it's not Steve Perry. Steve Augeri is the new frontman for Journey. |

| |

| In some years, Harry Caray's singing was the biggest draw at Wrigley. |

| |

| You don't have to tell actor Gary Sinese what an honor it is to sing at Wrigley. |

| |

| Jimmy Buffett and Cubs fans waste away another seventh-inning stretch. |