| ESPN.com: Page3 |

|

As "Friday Night Lights" his theaters this Friday and the ESPN Book Club debuts on Page 2, ESPN.com takes an in-depth look at the story of Odessa (Texas) Permian High School football: FROM THE ESPN BOOK CLUB: |

|

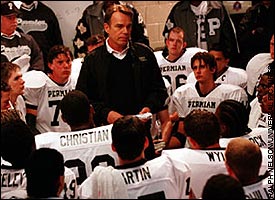

Check out a clip from "Friday Night Lights," Watch Coach Gaines deliver his locker room speech. |

| |

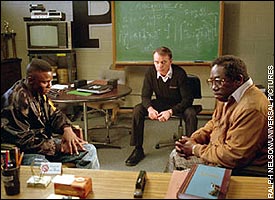

| It the movie, Permian coach Gary Gaines (Billy Bob Thornton) meets with Boobie Miles and his uncle, L.V., as Boobie decides to return to the football field. |

| |

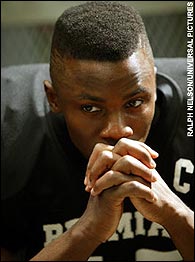

| Derek Luke plays Boobie Miles, whose senior season was cut short by a knee injury. |

| |

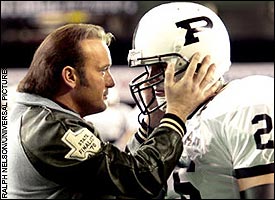

| The movie took some creative license with Charlie Billingsley (played by Tim McGraw) and his son Don. |

| |

| Although he was a legend at Permian, Charlie Billingsley never won his state championship in real life. |

| |

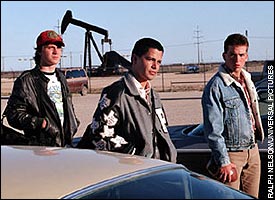

| The kids in Permian have football ... and not much else in "Friday Night Lights." |

| |

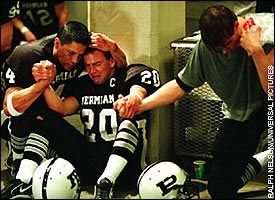

| Permian lost in the state semifinals in 1988, but the movie made it the championship game. |

| |

| The end was heartbreaking for Mike Winchell in Reel Life and Real Life. |

| |

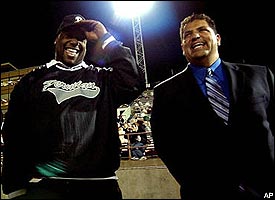

| The real Boobie Miles, left, shares a laugh with former Permian teammate Brian Chavez on the set of "Friday Night Lights." |