| ESPN.com: Page3 |

It might very well be the most familiar radio broadcast in the long, sordid history of Chicago sports. The Milwaukee Brewers were hosting the Cubs on Sept. 23, 1998. Chicago was locked in a tight wild-card race with the Mets and Giants. The Cubs held a 7-0 lead over Milwaukee entering the seventh inning -- just the sort of scenario a fatalistic Chicago fan greets with dread.

| |

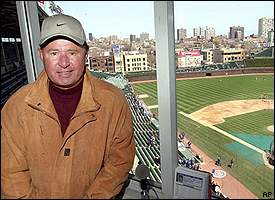

| Ron Santo played for 15 years (1960-74) in the majors, the first 14 of them for the Cubs. |

Ron Santo and Pat Hughes called the game on WGN Radio.

HUGHES: "Two down, the Brewers have the bases loaded, and a 2-2 count on the hitter. Here's the pitch. Swung on. Fly ball to left field. Brant Brown going back. Brant Brown ... drops the ball!"

SANTO: "Oh, nooooooooo!"

HUGHES: "He dropped the ball!"

SANTO: "Nooooooooo!"

HUGHES: "Three runs will score, and the Brewers have beaten the Cubs."

Hughes spoke flatly. Santo wailed. Listening to their broadcast, you could feel the sincere disappointment, a savage hatred for Brant Brown, and -- perhaps more than anything -- a profound desire to console Santo. The noise he emitted was the sound of pure grief.

Santo, who fell eight votes short this year to gain induction into the Hall of Fame, already embodied the most endearing qualities associated with Cubs players. But in that on-air moment -- as the Cubs' playoff hopes seemed to fade -- he became indelibly linked with the most endearing qualities of die-hard Cubs fans, too. This combination is conveyed warmly in "This Old Cub," a pitch-perfect documentary that chronicles Santo's life.

"After that game, I go down to the clubhouse and there he is with Cub manager Jim Riggleman," Hughes recalls in a scene from the documentary.

"I saw something that probably has not been ever seen before in a big league clubhouse. I saw the manager trying to cheer up the broadcaster after the game."

The resilient Cubs went on to capture the wild card in 1998, a fact that made Hughes' play-by-play call and Santo's agonized moaning more listenable over the years. It also has spared Brant Brown no small number of vicious epithets and barroom assaults.

The film quickly takes the viewer from Santo's boyhood in Washington state to his first Chicagoland home, on 74th Street in Elmwood Park. "This Old Cub" also reveals a private side of Santo's life: his recurring battles with the effects of diabetes, a disease that radically altered his life long before it claimed his legs. He was diagnosed with type I juvenile diabetes at 18 and played his entire professional career -- 2,243 major league games between 1960 and 1974 -- under its influence. It was a time when monitoring and regulating one's blood sugar was less exact than it is today. If Santo felt a little off during a game or his vision began to blur, he might eat a candy bar. Then he'd step in against Bob Gibson, Don Drysdale or Juan Marichal.

| "This Old Cub" documents Santo's remarkable career while also telling the story of his relationship with Chicago, a blue-collar city that quickly adopted the ostensibly blue-collar player. |

Chicago celebrities such as Bill Murray and Gary Sinise add commentary to footage from the Cubs' 1969 season. It was a year that ended badly for the team, but it retains a mythic quality for fans. Footage from 1969 in "This Old Cub" reveals the connection between the team and its fans, and the optimism that swept the city: "We're gonna shine in '69!" says Ernie Banks in spring training; Fergie Jenkins is mobbed by teammates after a victory; Santo is featured on the cover of Sports Illustrated under the headline "THE RAUCOUS NEW CUBS"; ecstatic fans pour onto the field after a win; Santo walks down a city street in a preposterous red hat and oversized sunglasses; he low-fives a cop after a game.

In 1969, he also began leaping in the air and clicking his heels after wins.

But that was midsummer. September went badly. The Cubs lost 11 of 12 games. The Mets surged. You know how it ended. "This Old Cub" channels the emotions of that season flawlessly.

However, the most effective scene in the documentary doesn't involve baseball. It was shot in poor lighting, with lousy audio, and the camera never moved. Santo has just woken up. He's shirtless and seated on the edge of his bed, beginning to put on his prosthetic legs. He slips thin white socks over his residual limbs, then inserts them into his prostheses -- the right one has a Cubs emblem on the side. He slides long, sheer sleeves over the legs. The process takes minutes to complete, and the small video camera keeps rolling, following the solitary daily routine of a 64-year-old diabetic and double amputee.

"This Old Cub" contains footage of Santo rehabbing from an amputation and film of him struggling up ballpark stairwells, but nothing is quite as intimate as the sight of him at the edge of his bed, donning his legs. And he never knew it was being filmed. His son Jeff Santo, one of the co-producers of the documentary, had -- for obvious reasons -- unusual access to his subject.

| |

| Santo remains a fan favorite at a recent Cubs Convention. |

"You know, my son, who is in the business -- a writer, a filmmaker -- really approached me on this. And the first thing I was concerned about was I didn't want anybody to see the private moments. Because those are the tough ones.

"He had this small camera. I said, 'Son, I can't have a camera following me around for a year. I'm going through too much.' And he said, 'Dad, I'm gonna be with you.' He's with me every day anyway. I mean, he's like my right-hand man. And he said, 'I'll bring a little camera.'

"I said, 'After we're out of the hospital and after we're feeling good, you know, we'll get the big cameras and we'll do this, and blah-blah-blah. But at home, always a small camera.' Well, he said to me, 'I want to film you getting up in the morning.' And so I said, 'I don't want to film with my legs off. In the hospital, fine. But at home, when I'm getting up in the morning, I don't want it.'

"I had no idea. And when I saw that piece, I couldn't believe it. But what a job. When I sat down to watch it, I couldn't believe it."

"This Old Cub" co-producer Tim Comstock understood Santo's initial reluctance to be trailed by cameras. He also knows why Ron eventually granted such total access.

"I think in the beginning, most of us wouldn't want to be filmed in those kinds of moments," Comstock said. "Going through what he has to go through each day just to get out of bed. But he's been involved with the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation the last 30 years, since it became a national foundation. What he goes through, and how optimistic he is, and how he keeps living a great life -- nothing slowing him down -- to show that on camera, to people who are thinking, 'Gosh, this is happening to me, life is not worth living anymore ... '

"He's proven to be the antithesis of that kind of thought. I think that's why he agreed."

A portion of the proceeds from the sale of "This Old Cub" merchandise, DVDs and VHS tapes supports the JDRF. According to Comstock, the film also has inspired entirely unanticipated acts of charity.

"Bill Holden, someone who watched 'This Old Cub' -- a 56-year-old guy who lives in Arizona -- he watched it. His son gave it to him for a present. He watched it five times. And he decided that what he was going to do for the JDRF, because that's Ron's charity, is walk twenty-one hundred miles from Arizona to Wrigley Field. He started a week and a half ago, and he'll arrive at Wrigley Field on June 30th. He's taking a backpack, and he's walking on foot the whole way.

"That's the sidebar about this story that's so unbelievable," Comstock said. "Wild Bill's Walk -- that's what we're calling it, and we're facilitating it for him -- hopes to raise $250,000. We decided that $5 from every DVD and VHS sold from the day he started, which is January 11th, till the day he ends will go to the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation. So we're hoping to raise a lot of money for them and find a cure for this disease."

| It's clear that the primary intent of the film was not to promote a man who's already a legend or to cash in on Cubs fan sentimentality. The hope is to aid the fight against a disease that affects millions. |

"Ultimately, by us selling videos, through ThisOldCub.com, we're creating awareness out there for the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation," Comstock said. "Not only what a devastating disease it is but also how optimistic we are, because of what Ron's done over the years and the many other people who volunteer. They're finding a cure. More awareness out there leads to more dollars and more good will. That's what we're hoping for."

Of course, had the film play a role in helping Santo enter the Baseball Hall of Fame, that wouldn't be so bad, either.

When asked to speculate about the possibility of entering alongside Ryne Sandberg, another iconic Cubs figure, Santo grinned.

"Oh, man ... " he said, rolling his head. "First of all, I was very excited Ryno got in. Timing is so important in life, about getting in. And there was no doubt in my mind Ryno, in his era, deserved to go in. First year."

He added, "This man had talent and played the game the way it should be played."

This is a common Ron Santo phrase: "Play the game the way it should be played."

Among other things, he means that a big-leaguer should play in every game he can -- despite his diabetes, Santo played 160 or more games in seven seasons. The phrase also refers to playing exceptional defense -- Santo won five Gold Gloves and led NL third basemen in assists seven straight years. Santo also valued the simple act of getting on base -- he led the league in walks four times and in on-base percentage twice. And for good measure, he topped 25 home runs and 90 RBI in eight straight years.

If his career looks good in terms of familiar stats and achievements, it looks downright scary-good when you consider more advanced tools, such as Bill James' Win Shares, that assess a player's total contribution to his team.

If James' metric is to be believed, at his peak Santo was simply the top player in the National League. In 1967, he led the NL in Win Shares with 38. (Not that anyone knew it at the time.) He had four more Win Shares than Cardinals first baseman Orlando Cepeda, the unanimous NL Most Valuable Player. In Santo's prime years, 1964 to 1967, he exceeded 30 Win Shares each season. During the 1960s, he was one of only three major leaguers to reach 30 or more Win Shares in four consecutive years. The other two were Hank Aaron and Willie Mays.

So why isn't the guy in the Hall?

Enshrinement by the Veterans Committee requires a player to be named on 75 percent of ballots cast. The instructions given to the committee are relatively simple. Here's the big one: "The Committee shall consider all eligible candidates and voting shall be based upon the individual's record, ability, integrity, sportsmanship, character and contribution to the game."

On the basis of those last four things, you'd think Santo's election would be a cinch. But given the number of famously racist or otherwise corrupt inductees, enshrinement often seems to rest solely on record and ability. On the surface, Santo looks good there, too.

"But a lot of people say, 'Hey, that Cubs team has three Hall of Famers already,' " Comstock said.

"They've got Fergie, Billy Williams and Ernie Banks. And for a team that never won the World Series, they shouldn't have four."

This logic, however prevalent, treats the other 21 players on the Cubs roster as scarcely relevant to the team's success. And it ignores the notoriously bad and broken starting pitchers who lurked at the bottom of the Cubs rotation in the 60s (see "Broglio, Ernie.") And it discounts the fact that Chicago was, in fact, a good team for a protracted period of time, finishing above .500 in every season from 1967 to 1972.

"There's also a bias, if you look at baseball, against third basemen. That's the most underrepresented number of Hall of Famers," Comstock continued.

When Santo retired after the 1974 season, there were only three players at his position enshrined in the Hall: Pittsburgh legend Pie Traynor, dead-ball era great Frank Baker and 1890s star Jimmy Collins. No third baseman had been enshrined since 1955. The Veterans Committee eventually would add two Negro League stars, Judy Johnson and Ray Dandridge, and two very good hitters of the distant past, Freddie Lindstrom and George Kell. Baseball writers added Eddie Matthews, Brooks Robinson, Mike Schmidt and George Brett. Of the 212 players in the Hall, only 12 of them -- including 2005 inductee Wade Boggs -- are enshrined as third basemen, according to the Hall's Web site. It's the lowest total at any position.

Santo narrowly missed enshrinement by the Veterans Committee this year and two years ago, he missed by 15. His disappointment at hearing the news in 2003 is one of the more difficult scenes in "This Old Cub."

| 'This Old Cub' on DVD |

|---|

| To purchase Ron Santo's life story on DVD, visit the official online store of 'This Old Cub'. |

"It's like anything in life," he added. "Timing is everything. My timing with the Hall of Fame has not been good."

But Santo is feeling unusually good at present and looking forward to the 2005 season.

"In '99, I had a quadruple bypass. In 2000, I was clean. In 2001, I had my right leg done. Then my left leg. And then bladder cancer. And this year, nothing. Very healthy. I've been working out a lot so, I'm doing great."

That, of course, is better news than anything the Veterans Committee could possibly decree. Fans who have followed Chicago sports at any point in the last 45 years recognize that a Hall of Famer is the least of what Santo is. They don't need a far-off plaque to appreciate him. They have "This Old Cub" to remind them of what Santo means to Chicago baseball, and the replay of the collapse in Milwaukee to remind them of what Chicago baseball means to him.

Andy Behrens is a freelance writer in Chicago.