Playground Basketball Is Dying

Once an American staple, hoops on blacktops across the United States has all but faded away.

AT RUCKER PARK in New York, people sat on rooftops and climbed trees to watch Julius Erving play. In Louisville, Kentucky, Artis Gilmore would pull up in his fancy car, still wearing his fancy suits, and just ball. Kevin Durant first measured the worth of his game on the D.C. playgrounds, and Arthur Agee chased his hoop dream in Chicago. The Philadelphia outdoor courts once boasted a who's who of the city's best ballers, and in Los Angeles, playground legends with names such as Beast, Iron Man and Big Money Griff played on the same concrete as Magic and Kobe.

That was then, a then that wasn't all that long ago.

Now? Now the courts are empty, the nets dangling by a thread. The crowds that used to stand four deep are gone, and so are the players. Once players asked "Who's got next?" Now the question is "Anyone want to play?" And the answer seems to be no, at least not here, not outside.

Playground basketball, at least as we knew it, is dying.

"That's gone now, all of it is gone," said former University of Maryland star Ernie Graham, who honed his game on the playgrounds of D.C. and Baltimore.

There is no single cause. The best players, young and old, want to be inside instead of out; they want organized games to showcase their skills, not pickup games to earn street cred. Violence has chased people off playgrounds and out of parks, and NBA and NCAA rules limit when and where guys can play in the offseason.

"I think a lot of guys don't think it's worth it," said Toronto Raptors guard Kyle Lowry, who just signed a four-year deal worth $48 million.

That attitude starts at an early age. High school players in search of scholarships and exposure spend May, June and July in indoor, showcase tournaments and AAU (Amateur Athletic Union) events, not parks.

"AAU is a big milestone for anybody," said D'Angelo Russell, a five-star Ohio State signee from Louisville. "If you're not playing AAU, you'll be lucky to get out of your own city. AAU helps any kid. You get to play in front of top colleges, play with the top players, against the top players. You get to make a name for yourself every day you play."

Playgrounds were once so active. Over time, the courts have become quiet. Where did all the players go? Where did all the games go?

But the appeal of an indoor game isn't just the quest for fame, scholarship or structure. It's also about safety. It's easier to control an indoor space than an outdoor one. Buildings have walls and private entrances; you can't put a metal detector at every park.

"You're not going to go out and see LeBron in the playgrounds unless there's a special setting, a special arrangement," said Gilmore, a Hall of Famer. "Because the other thing is security. Kids right now, the way they value individual guys' lives, it's not the same."

Even if the NBA stars are made to feel safe, they aren't likely to show up. Kobe Bryant broke his wrist on the hard concrete at Venice Beach in California. Locals swear the concrete D.C. courts at the Goodman League ruined Gilbert Arenas' knee. The fear of injury, missing games and losing money, coupled with jam-packed offseason schedules, has turned pros into occasional visitors rather than regulars at the nation's playgrounds.

"Dominique Wilkins played outside, and he could still jump," said Taras Brown, a longtime AAU coach and Durant's godfather. "They say they're worried about their knees. Your knees don't go 'til you're in your 40s. They just don't want to play outside anymore."

NBA players will not play outside anymore; NCAA players largely may not. College rules restrict summer league participation.

"Summer school is so prevalent, I almost feel sorry for our guys," Gonzaga coach Mark Few said. "They get 10 days here, and then the first summer term starts up. Then another week and the second summer term starts up. It used to be you released a guy in May, gave him a workout plan and hoped they did what they were told. You wanted them to play."

Kids still want to play basketball. They still do play basketball, but not outside, not at playgrounds, not like they used to.

Tour the country, visit the playgrounds in New York and Los Angeles, Chicago and Louisville, Philadelphia and Washington, D.C.

See how it used to be, see what it's become, and see and hear what we've lost.

NEW YORK

Jason Madara

THE COUPLE, as Bob McCullough remembers it, were French. They were walking up Frederick Douglass Boulevard when they spied the small plaque hanging on the side of the fence:

RUCKER PARK.

"They stopped and took a picture," said McCullough, a smile spreading across the 73-year-old's face. "That's why things won't die here. Everyone wants to play here. Everyone's heard about Rucker Park."

If there is a holy ground of playground hoops, it is the space here near 155th Street, just off the Harlem River Drive. The Harlem Garden, old-timers used to call it, and it is hardly hyperbole. If Madison Square Garden is billed as the world's most famous basketball arena, this is its outdoor cousin.

This is where Julius Erving shucked the nickname given to him by a Rucker announcer -- The Claw -- and argued to be called The Doctor. This is where Allen Iverson and Stephon Marbury, fresh off being selected as the No. 1 and No. 4 picks, respectively, in the 1996 draft, partnered for a dream backcourt; this is where Rafer "Skip to my Lou" Alston went from local legend to NBA player; and this is where Kareem, Dominique, Wilt, LeBron, KD, Kobe and so many other first-name-only star players have dropped in for at least one game in their respective careers.

But this is also where playground basketball's crossroads come most glaringly into focus. Rucker is still Rucker, with all its resonance and meaning, but it is not Rucker, not the one seen in the old, grainy videos, with fans literally sitting on rooftops and climbing tree branches to get a view. On a recent July night, there were plenty of seats to be had as DG Films upset Sean Bell, the two-time defending Entertainment Basketball Classic tournament champions. Even seats on Sean Bell's bench were empty.

Rucker might be the place everyone wants to play, but Sean Bell's team could muster only six guys.

"It's not the same," said Greg Marius, who started the EBC 32 years ago. "When I was growing up, everybody in the hood played basketball. Everybody. Now they're all doing something else."

This isn't about violence.

Harlem is in the process of a rebirth, experiencing economic growth and development not seen since its Renaissance heyday in the 1920s. Besides, Marius doesn't allow for any extracurriculars. Outdoor games in other parts of the city might include the ambient mix of marijuana and alcohol, but not here. Orange-shirted security people check bags before fans can enter the park, and the police presence inside and outside the gate is heavy. This is strictly ball, not basketball surrounded by a circus.

And it's not about injury. Two years ago, they laid down a hardwood court at Rucker. At night, it's covered by a tarp; in the winter, it's taken up entirely. It can get a little slippery on a humid night, and even the slightest bit of rain forces the game to nearby Gauchos Gym, but players can't complain about wear and tear here.

No, the problem at Rucker goes more to the root of the entire issue with playground basketball. There just aren't enough players.

"There's another tournament every 30 blocks," Marius said, speaking to Rucker Park, to the Dyckman League's 24-year-old tourney, to events at Hunter College in Manhattan and at Orchard Beach in the Bronx . "It's all the same players going from one to the next. It waters it down."

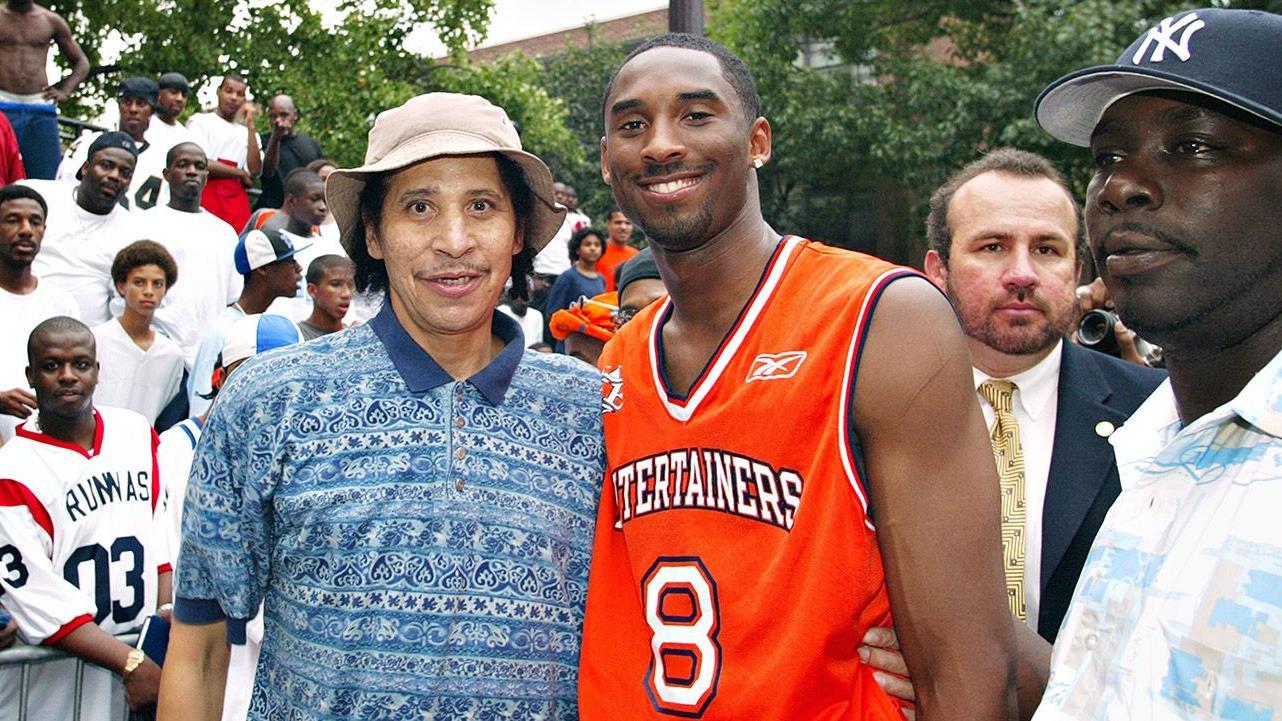

Pros don't stop in and play at Rucker Park as much anymore. But in 2002, Kobe Bryant stopped by and put on a show.

Of course, it once didn't matter who played, just that there was a game to watch. Holcombe Rucker, the director at what was then known as P.S. 156, started a basketball tournament in 1947. There were no grand plans, just a hope to give kids something positive to do.

McCullough was one of the kids he took care of, the two growing so close that McCullough joked that Rucker's wife, Mary, thought "I was his hidden son."

Rucker died of cancer in 1965, and McCullough, just finishing up his degree and career at Benedict College in South Carolina, took over his mentor's duties. He added to Rucker's new semipro/pro division, making things a little fancier by supplying the players with uniforms.

Before long, Rucker became the place to play, but fans weren't just drawn by the likes of Dr. J; they came to see playground legends, too, guys such as Fred Brown and Earl "The Goat" Manigault.

At this year's opening celebration, Brown stood outside the gates of Rucker in a pair of linen khaki slacks and a tan shirt. Still fit and trim, Brown had no plans to play that day, but he was happy to be back -- back on the court where he made a name for himself.

"People didn't care if you were 20, 30 or 50; if you loved the game, you played, and people respected you for it," Brown said. "Now it's more commercial. It's about individuals. People want to see certain players. We came to watch the games."

And that's the one riddle not even Rucker can solve.

In an age when virtually every NBA and college game is on television, when players are brands as much as people, folks don't come out unless they think it's worth their while.

"When James Harden played here last year, in five minutes, it's around the city and you couldn't move," said Dee Lancaster, who coached Harden in that game last year.

But what if it's just Brandon Whitaker, a local kid about to enter his senior year at Division II Concordia taking on the man known as The General, the two-time tourney MVP for Sean Bell?

Why isn't that enough?

Why isn't a good game on a warm but comfortable Wednesday night in July, on the fabled Rucker Park court, enough?

"It didn't used to matter how hot it was or who was playing; the place was packed," Marius said. "Now it's, 'Oh, it's hot,' or 'Who's coming?' or whatever. They only come out if it's a big name. I don't know. I don't know where basketball is going. In 20 years, Rucker will still be here. My kids can take over. But I'm not sure what it will be."

LOS ANGELES

BEAST LURKS AT Venice Beach, according to those who know these courts well.

They don't know his real name, his address or his cellphone number. On the playground, game trumps names.

"Beast just walked up," announced Bryan C. Jones, who knows the L.A. basketball landscape.

Years ago, Venice Beach and the other fabled outdoor courts of Los Angeles produced similar legends recognized by monikers alone. If you could ball, you could play next to the rich and famous, even if you had only street credentials.

But as the years passed, the best basketball players on the West Coast began to take their talents to the polished floors of air-conditioned gyms and reject the concrete that nurtured a former generation's best ballers. Their young admirers followed as L.A.'s playgrounds were gradually stripped of their most talented athletes.

Six-foot-6-ish, 260-pound Tarron "Beast" Williams can be found on Google. He did, after all, win the 2013 Red Bull King of the Rock streetball tournament. But finding him, and those like him, on the playground these days isn't so easy.

"[Outdoor] basketball here in California ... it got watered down," said Williams, a former Division II power forward at Cal State-San Bernardino who got his nickname from L.A. icon Baron Davis. "Kids are not into playground basketball like we were."

That's the truth.

The men who've witnessed the shift try to preserve its fabric and history while penning its obit. Today, these outdoor surfaces no longer breed the Jumpin' Joey Johnsons, the Hooks, the Bad Santas, the Worms and the Beasts -- street legends -- who were so popular in the '70s, '80s and '90s.

"It's dead," said Jon Nash, who created the popular Venice Basketball League in 2008 to restore playground basketball in L.A. "I don't want to put it out there like that, but..."

Throughout the first weekend of June, the search for high-level outdoor basketball became an elusive pursuit in the City of Angels.

Palms Park off Overland Avenue? One boy takes a few shots and disappears. Marine Park? The beautiful gem tucked into a neat Santa Monica neighborhood is empty. Mar Vista Park has multiple courts available midday, but not one 5-on-5 run. Darby Park is packed, but only thanks to an organized exhibition between a group of streetballers and a team of female former Division I players (the women won).

"It's not as good as it used to be," said former Washington State guard Jerry McNair, who played one-on-one with a friend on an otherwise empty court at Westchester Park.

At Rogers Park, a handful of young men dribble on the gravel positioned down the hill from yellowed grass patches that thirst for water and attention. There are more boys pulling off kickflips and ollies on skateboards than basketball players getting buckets.

Tarron "Beast" Williams, a former college basketball player and local playground legend, describes the outdoor basketball scene at L.A.'s Venice Beach.

This is a difficult and new reality for Dwayne Polee Sr., a former playground and prep legend in Los Angeles, to digest.

He was just a teenager when then-NBA standouts Michael Cooper, Marques Johnson and Magic Johnson would join youngsters for offseason matchups that allowed the top kids in Inglewood to play against future Hall of Famers and college standouts.

"All the greats in L.A. and even other pros would come to L.A. in the summertime and show the young kids how to play," said Polee, who played at Pepperdine and was drafted by the Los Angeles Clippers in the third round of the 1986 NBA draft. "Magic never had bodyguards. These guys would come in the city and be comfortable."

The pros are still comfortable in the city. They're just not outside.

The Drew League, which grew in popularity during the NBA lockout in 2011, is the smartphone to playground basketball's rotary dial. LeBron James and Kobe Bryant have played here. Kevin Durant is scheduled to compete this summer, too.

A private lot secures the Range Rovers and BMWs in the back of King Drew Magnet High School of Medicine and Science in Compton, which hosts the Drew League. The best players, Beast among them, arrive with girlfriends who dress for the red carpet, not a summer pro-am. Baron Davis coaches a team in the league. Nipsey Hussle, a West Coast rapper, cheers from the front row.

"It's very competitive," said former USC guard J.T. Terrell, who plays in the league. "That's what I like about it. It's the best place to play in L.A. You've got pros from all over out here."

There are many theories that attempt to explain the exodus from L.A.'s playgrounds. People don't want to ruin expensive footwear. There are concerns about injuries. Violence, too. But it might not be that complex. Elite players seek top competition, and that's not consistently available outdoors in 2014.

If you're lucky, you can find a game in Los Angeles. But it's a crapshoot.

"[Outdoor] basketball here in California ... it got watered down. Kids are not into playground basketball like we were."

- Tarron "Beast" Williams

Mar Vista Park, mostly empty earlier that day, is buzzing in the evening. There are games on three courts and a collection of players trying to sort out who called next on this illuminated court.

Demetri Miller, 18, travels the 25 minutes from South Central L.A. to play at Mar Vista Park on Friday nights. He always finds a good game, he said. But he wishes L.A. had more competition and activity on other outdoor courts.

"You can't just go to a park in L.A.," Miller said, "and see people playing like this."

Venice Beach, the locale of the movie "White Men Can't Jump," remains vibrant and alive, though. Many gather to watch Williams and his teammates battle in the Venice Basketball League.

Eleven-year-old DJ Kiss has a staff that pushes his brand's T-shirts to spectators while they bob their heads to the rap instrumentals he blasts from his full digital setup. The VBL's emcee, Mouthpiece, assigns names to the players who've clearly competed beyond the recreational level.

The twins are Mario and Luigi. One of the few white guys on the court is That '70s Show.

But Beast isn't having fun. He's missing shots and layups. And he can't buy a call. "Man, call the foul!" the VBL's three-time MVP yells at one of the referees.

He's screaming because playground basketball isn't just some pastime to him.

It's everything. And, like this bad game, playground basketball itself is slipping away.

CHICAGO

WHENEVER JABARI PARKER, the No. 2 pick in last month's NBA draft, yearned for the grind that the runs on the South Side's playgrounds once promised, Sonny Parker would dial friends in the area and ask them to watch his son.

"It's not even safe going to certain places," said Sonny Parker, the 17th pick in the 1976 NBA draft. "Back in the day, we'd get a pass, and we'd get a warning. 'Hey, something's about to go down.' ... Things have changed. When [Jabari] came to the park, I had to let people know he was coming through."

Violence is an issue in America, but it saturates Chicago, a city that once hosted some of the best playground basketball in the country. The city's police are working overtime shifts this summer in parks to curb crime, according to a CBS report.

There were 503 murders reported in Chicago in 2012, the highest total in America that year. That number dipped to 415 in 2013, still the highest.

Parks and playgrounds have been stages for some of the violence.

Last year, Hadiya Pendleton, a 15-year-old who had participated in President Barack Obama's 2012 inauguration festivities, was killed at Vivian Gordon Harsh Park when a shooter ambushed a group gathered under a canopy. Thirteen people, including a 3-year-old boy, were wounded in a September shooting at Cornell Square Park. And that shooting began when a gunman attacked those playing pickup basketball.

The violence persisted over the recent Fourth of July weekend when a 44-year-old woman reportedly was killed at Morgan Park. More than 80 people in Chicago were shot, and 16 died, over the holiday weekend, per reports.

"Parks have become so vulnerable," said Rev. Michael Pfleger of the South Side's popular Saint Sabina Church. "It's easier to get a gun than it is to get a computer in this neighborhood."

Violence is the refrain in a city sacked by heavy pockets of trouble. So the front pages read -- bleed -- like Agatha Christie's novels. As a result, fear has cleared some of Chicago's former basketball havens.

"[Violence] plays a big part in it," said Rob Graham, a Chicago native and local sports marketing executive. "I drive past the parks now looking for games to see, but you can tell that it's not like it used to be."

Miles Rawls, commissioner of the Washington, D.C.-based Goodman League, urged officials to move the upcoming Tournament of Champions, a Nike-sponsored streetball showcase, to another city. He has been assured that competitors will play indoors for next month's event.

"I called my Nike rep and said, 'Y'all can't be putting this together in Chicago,'" Rawls said. "It's a big, big concern. ... They're not playing outside at all."

Think about that: The outdoor championship had to be moved indoors.

On one West Side street, there are homes with broken glass and barred windows. Across the street, trimmed bushes abut small flower gardens in front of two-story, stone anomalies in this tough West Garfield Park neighborhood.

Parks should be the sites of basketball games, not crime scenes. Scott Olson/Getty Images

Arthur Agee Jr. stops in front of his boyhood home and rolls down the window.

"Follow me," said Agee, the Chicago-born star of the 1994 "Hoop Dreams" documentary.

He zips through the alleys on his way to Delano Elementary School in his SUV. A Black and Mild cigar balances on his lower lip.

He arrives, parks and shakes his head as he exits the car.

The playground is empty.

On this court, Agee once dazzled crowds with acrobatics that encouraged director Steve James to focus on Agee's and William Gates' basketball journey in the film that won the Audience Award for Best Documentary at the 1994 Sundance Film Festival.

In mid-June, Agee stood on that court with a few friends -- including Shannon Johnson, who also appeared in the film -- and a cameraman capturing the scene as part of an upcoming reality TV project. There were no kids. No games. The thump of basketballs bouncing on concrete, a sound that once signaled summer in America, was absent.

He's not surprised.

"This community has changed, as far as the violence," Agee said. "Ain't no protection."

With the standing room taken, Johnson had to climb onto the school's rooftop to watch the older guys play when he was a kid. The troublemakers never interfered. The court was a safe zone.

"This would be sacred ground," Johnson said. "Now, stray bullets might come through."

There's no indication that this court will fill anytime soon.

But Agee won't end the pursuit. He's certain the next stop will feature a buzzing playground scene.

"Hey, let's go to Garfield Park," he said.

But Garfield Park is clear, too.

It's not just neighborhood parks, either. Even well-known Jackson Park, where Billy "The Kid" Harris once ruled, isn't packed.

A father and his young son practice alone on Lincoln Park's courts. Five teenagers play at Horner Park, which, they say, hosts good games all summer. Four of the rims don't have nets, though. The courts weren't rumbling at nearby California Park, either.

This is not an indictment of the Windy City's basketball crop. Prep programs such as Simeon and Whitney Young have pumped out talent for decades. Dwyane Wade, Derrick Rose, Anthony Davis and Tony Allen all developed here. Jabari Parker, the Milwaukee Bucks' young star, was a standout for the Mac Irvin Fire powerhouse AAU team. Duke's Jahlil Okafor and Kansas' Cliff Alexander, ranked first and third, respectively, by RecruitingNation in the 2014 class, are Chicago products.

It's just difficult to find that caliber of talent outdoors. The elite play in the Nike-sponsored Chi League. Sonny Parker operates a few indoor leagues, too. The city opens rec centers Friday evenings and Saturday mornings to give local youth a "safe, healthy place to play," according to its official website.

"Parks have become so vulnerable. It's easier to get a gun than it is to get a computer in this neighborhood."

- Rev. Michael Pfleger of Saint Sabina Church

"You don't see the best players in the park," Sonny Parker said.

The violence isn't just some secondhand experience for folks in this basketball community. Its imprint is tangible. Children travel to school via safe routes. Agee's father, Arthur Agee Sr., was robbed and killed in 2004. Pfleger's foster son was killed a few blocks from his church in 1998.

Pfleger has tried to use basketball to bring peace. Participants in his church's Peace Basketball Tournament are rival gang members who compete in violence-free matchups. He believes the games will affect the community as former enemies bond through hoops.

Yet, it's not enough.

"Basketball alone ain't gonna do s---," he said.

But it's still fun and a temporary escape from the chaos in certain parts of the city. Agee, 41, finally finds a game at Moore Park. And he feels 12 years old again. He doesn't drive down the court as much as he shifts his legs into neutral at times and idles toward the cup. Age will do that to even the best.

It's hectic. False fouls called. Legit fouls ignored.

"You don't know nothin' about basketball, man!" one of the youngsters yells. "What do you mean?! That was out!" another responds.

Agee is in the mix, too. He's directing his team. Demanding more unison and cohesion.

"Listen, all I'm doin' is passing," he said. "That's fine with me."

It's tied 32-32 when his team's turnover leads to a fast break and finish on the other end. Game over.

This used to be the norm on the Chicago playgrounds in Sonny Parker's day. He'd play all day, and the moment his team lost, a new five would arrive, and the games would continue. So Sonny Parker would wait along the baseline for another chance to run with the basketball kings of his community.

The best kids from one block would go at it with the best another neighborhood had to offer. A thirst for pride and respect was their motivation.

He never wondered whether there'd be a game -- only where he'd go.

WASHINGTON D.C. & BALTIMORE

MOSES MALONE, as legend has it, played one game in a Big M Trotters tournament and was named MVP. Ernie Graham, the Maryland star, cut his teeth in those tournament games. It was at the Big M that legendary Georgetown coach John Thompson discovered Ed Spriggs, the man who spent his senior season toughening up a spindly freshman by the name of Patrick Ewing.

The M in Big M stood for Melvin, as in Melvin Roberts, the man who sponsored the tournaments and built the court at 700 Eastern Ave., just over the Maryland border from D.C.

To make things easy for himself, Roberts built the court adjacent to his business, Melvin's Crabhouse. And so on a summer evening, folks could gather to watch local legends all while enjoying the local delicacy for dinner.

"There were people all over the place, music, good crabs to eat -- it was like a cookout," said Graham, who used to drive in from Baltimore. "Teams from all over would come."

That a basketball court ended up next to a seafood joint, built by a business owner who was more civic leader than entrepreneur, said everything you need to know about the once-vibrant playground basketball history in this area.

From Baltimore's Dome (aka Madison Square), to the King Dome in Seat Pleasant, Maryland, to the Goodman League in D.C., to Melvin's, it wasn't a matter of finding a game; it was about deciding which spot had that night's best run.

During the day, those same courts teemed with young kids pretending they were the old heads they had watched play the night before.

Now those courts, much like the leagues, are quiet. Back when Kevin Durant was a skinny, 13-year-old kid, his godfather and mentor, Taras Brown, took him to the King Dome, at the corner of Addison and Sheriff in Seat Pleasant. As Brown saw it, "He needed to go where the pole don't move and everybody plays physical because nobody wants to fall down."

On a recent, sunny, June afternoon, that same playground was deserted.

Melvin's ... it's gone, too. The business closed eight years ago, and the property, along with the basketball court, was put up for sale. Roberts passed away in 2011.

"It's all lost now," Graham said. "I have a 22-year-old son [Jonathan, a senior at Maryland], and he's never to my knowledge played outside. I know these younger guys think we're hating on them, but they had to experience what we did to appreciate why it was so special. And they never will."

For the most part, the culprit here is no different from anywhere else -- AAU tournaments pulling kids away in the summer, college players spending time on campus, neighborhood violence spilling onto the courts -- but the real killer of playground hoops in the D.C.-Maryland-Virginia area is apathy.

There are fewer people selfless and dedicated enough to run the games, and consequently the games are literally dying with the passing of aging organizers. In Baltimore, for example, the Cloverdale Baltimore Basketball Association at Reservoir Hill shuttered with the passing of Lorenzo "Mike" Plater, who ran the league until his death at age 79, two years ago.

What's left is an era holding on for its last breath. Two strong-willed men are keeping two leagues alive -- Jeff Johnson at the Watts League in the Northeast section of D.C. and Miles Rawls at the Goodman League on the Southeast side -- but will they help rejuvenate the playground scene or simply serve as its pallbearers?

"We're not going to die out," Johnson said. "Won't let that happen."

Rawls is equally determined.

"When they dig [the court] up, that's when it's going to be done," he said of the Goodman. "Until then, we're playing outside."

But he also knows what he's up against.

He's been Goodman League commissioner since 1996, taking over after the league practically disappeared amid disorganization. An employee of the Department of Homeland Security, he grew up in the Barry Farm public housing community, played in the Goodman League as a kid and now spends every summer evening at the court off the alley of Firth Sterling Avenue.

He has seen what the league can do for the area: According to a Washington Post story, there were zero crimes committed within 100 feet of the court in 2011, compared with 165 crimes 1,000 feet away -- but he might be the only stopgap between the Goodman's existence and extinction.

"Without Miles, there is no Goodman League," said Mac Williams, coach of Team Ullico.

And even Rawls might not be enough.

The city has big plans for the Barry Farm area. Although currently stalled, there are plans for an area revitalization to include retail shops, a Metro stop and new housing -- perhaps even where the basketball court currently sits. Even if the court itself isn't dug up, a neighborhood changeover could significantly alter things.

At the playgrounds, you'll get a little of everything, from ballers to showmen, plus music and ice cream. Daniel Bedell for ESPN

Most of the people who play here and who sit in the stands grew up in and around Barry Farm.

"I started right over there,'' said Hugh Jones, motioning to the side courts where little kids played. Jones, better known by his AND1 name, Baby Shaq, is 34 now. He's in his 13th season in the league. "I had to wait my turn to get on the main court. It's all I had.''

If the area changes and the people that call it home scatter, what exactly would be lost? Basketball, yes, but it's more than that.

Playground hoops is a conduit for community.

To come to the Goodman League today is to get a sense of what playground ball was in its heyday.

Folks started to stream in a little before 7 p.m., some stopping by the food tents in the corners for dinner; the catfish drew particularly rave reviews. Charles Holmes, known as Season Ticket, set up camp chairs along the sideline. He's the leader of a collection of "season-ticket holders" and swears he hasn't missed a game in 12 years.

A girl zigzagged her motorbike across the court while players warmed up, and three guys behind the DJ tent boldly lit up a blunt, adding to what -- by the end of the second game -- will be an unmistakable haze.

Two locals, The Undertaker, cane in hand, and Hot Dog, roamed the courts freely. Although neither has any official purpose, both screamed at the refs, yelled at the players and strutted on the court.

Rawls, still trim at 52, worked the mike like an unfiltered, caustic Al Michaels, mixing play-by-play with opinion, reaction with trash talk, shoutouts to guys in the bleachers with instruction to the officials. "Ladies and gentlemen, for the first time in Funkhouse history, we have a Caucasian on the roster," he said. "But we're going to call him Black Steve."

Black Steve, no doubt a little shaken, then proceeded to stutter-step through his first possession, got caught between a pass and a shot, and heaved up a disaster of a nothing -- to which Rawls said for all to hear, "What the f--- was that, Black Steve?"

Everyone laughed, even Black Steve.

But if the atmosphere and the energy is the same, the game is not as good as it once was.

"Nah, it's watered down," Rawls admitted.

Once the city's best players came here. When Durant turned 16, Brown drove him and Ty Lawson to the Goodman League so they could see exactly how good and how tough they were.

Now the league is made up mostly of ex-college guys who either have graduated and are playing pro somewhere or have flamed out and are looking for a reboot.

The league isn't certified, so Division I players can't participate. Rawls spent the $1,800 in insurance money three years ago to meet NCAA requirements, but then the Division I guys all stayed over at Georgetown's McDonough Gym anyway.

So what's left is a game that is good, but not nearly as good, and an era that is alive but with a faint pulse.

"I was not at the top of the basketball world when I was a youngster," Graham said. "But I played with the best, and eventually I caught up and people respected me for that. They saw how proud I was to wear my T-shirt and represent where I came from. That's what it was about, and now it's all gone -- all of it is gone."

LOUISVILLE

CORNELL BRADLEY RECALLS every detail.

The audacity. The anticipation. The acrobatics of Darrell "Dr. Dunkenstein" Griffith, who led Louisville to the 1980 national title.

In the early '70s, a teenage Griffith drove to the rim against 7-2 Artis "A-Train" Gilmore, who was with the Kentucky Colonels of the ABA at the time, in the Dirt Bowl at Shawnee Park.

Then, Griffith rose...

"What went down was Artis Gilmore was back underneath the basket, and Darrell Griffith come driving to the basket, and Griff just went up over him, man, and dunked it on him," said Bradley, the Dirt Bowl's longtime emcee. "Dunked on him. And when he dunked on him, the crowd went wild."

"AAU has changed the game, and it's really changed the game a lot. We've got a lot more indoor basketball than we have outdoor basketball now."

- Marty Storch, Louisville's deputy parks and rec director

But Gilmore doesn't recall those details.

"I don't remember [getting dunked on]," he said.

Even though the playground culture has changed, the Dirt Bowl, in its 44th season, remains an urban basketball gem tucked into the corner of the Bluegrass State's largest city.

In 1969, Ben Watkins, who played at Jackson State, wanted a tournament that would draw the area's best to one spot. So he created the Dirt Bowl.

It exploded. Quickly.

Watkins remembers 6,000 folks swarming Shawnee Park to watch the games. There were so many fans you couldn't see the court as Griffith, Gilmore and Hall of Fame power forward Wes Unseld dazzled.

If there's any hope that basketball on concrete might find its second wind, it's here in this weekend event that's embraced by the city and community.

And if there's any proof that playground ball will never be the same because of the swift migration indoors, it's also here.

"They're coming together for one common goal, just to play some basketball and excite the people in the community," said Neal Robertson, president of the West Louisville Urban Coalition and a former local high school star who runs the Dirt Bowl.

On a Sunday afternoon in late June, men don't just sweat, they melt in the 90-degree heat. Still, Bradley's catchphrases and one-liners enhance the atmosphere.

"Yeah, he got that good hair."

"Uh-oh, he's hurt. Oh no, he's hurt. ... Wait, he's back up. He's back up. He's hard!"

"Bang! I said bang!

Opposing coaches and players from the two dozen teams stroll through the park.

"It's about recruiting," said Milton Ritchie, who coaches one of the teams, Unfinished Business. "I want the best squad."

About a dozen Louisville cops monitor the scene from a small picnic table.

Violence in the 1990s and 2000s led to a brief hiatus for the Dirt Bowl. Shawnee Park was also the site of a triple shooting three years ago. A 22-year-old man was killed, and two others were wounded. Mayor Greg Fischer helped restore the legendary tourney in 2012 after his election.

"It used to be a gang-infested environment to where there was a lot of shooting and people just couldn't enjoy themselves," said Larry Woods, who helped operate the Dirt Bowl in the 1990s. "But now it's changed to where we've got a lot of protection down here. We're really enjoying ourselves this summer."

Cornell Bradley, longtime emcee at the Dirt Bowl in Louisville, looks back on the day when a young Darrell Griffith dunked on Artis Gilmore.

"We had teams from all over the state of Kentucky," Watkins said. "The Kentucky Colonels were playing here. They could play. The high school guys could play against the pros. The pros could play against the top college kids. It was just amazing. And it just grew and grew and grew. If you played ball in Kentucky, you had to come through the Dirt Bowl to be anything. If you didn't play in the Dirt Bowl, you wasn't nothin'."

Griffith, Unseld and Gilmore viewed the summer matchups on these outdoor courts as opportunities to compete with the best players in the area and boost their street cred. Not Montrezl Harrell.

The Louisville big man is listed at 6-8, 235 pounds. He could be an NBA lottery pick in 2015. Everyone in the park wants to see him play. He doesn't think that's a good idea.

"I don't have anything to prove out here," Harrell said. "I don't have nobody to go against out here. My competition and my goals are playing against guys that are in college."

Guys such as Harrell used to be regulars. Algonquin. Chickasaw. Wyandotte. These Louisville parks were once flooded with local talent. There's only a sprinkle now. AAU basketball is one of the culprits.

"AAU has changed the game, and it's really changed the game a lot," said Marty Storch, Louisville's deputy parks and rec director. "We've got a lot more indoor basketball than we have outdoor basketball now."

Adrian Tillman thrives in both worlds. The local high school coach competes in the Dirt Bowl. But he also guides his daughter's ninth-grade, nationally ranked AAU squad, Louisville Team Shively. He wants to send Jamari Tillman and her teammates to college.

So he has hired a personal trainer. Jamari has another trainer who specializes in footwork.

She lives in the gym. The playground game is like a pager or a Walkman to her generation -- something the kids have only read about.

A few weeks ago, however, Tillman invited the young women to the Dirt Bowl so they could witness what he experienced as a kid roaming Louisville's favorite courts.

But he lost the crew in the crowd.

He found his players on a separate court. They had grabbed a few basketballs from his truck and challenged a group of boys. On their way home, they asked Tillman to stop at another playground.

"They were actually excited about being at a park," he said. "My jaw dropped."

Not the first time that has happened at the Dirt Bowl.

PHILADELPHIA

THE CRACK RUNS smack through the center of the Cherashore Playground basketball court, a nasty-looking gash that splits the unforgiving concrete like a fault line.

And when Ja'Quan Newton tripped right where the line snakes across the macadam, meeting the pavement with a splat and a slide, someone in the crowd summed up the that's-gotta-hurt crowd reaction succinctly.

"Damn!" he shouted.

Sitting in the stands, Joe Newton physically recoiled.

Years ago, Joe brought his son here, to the Chosen League played on a court at 10th and Olney in Philadelphia. An accomplished player himself -- he was Division II national player of the year out of the University of Central Oklahoma -- Joe knew from personal experience that tough players, especially point guards like him and his son, weren't developed on the sterile confines of high school gyms or even rec centers. They were cultivated on the outdoor courts, like the Southwest Philly ones Joe once called home.

But that was before Ja'Quan signed with the University of Miami, before so much was on the line.

"Did you see him fall?" Joe Newton said an hour later. "I was like, 'Oh no. Man, he's going to Miami. That can't happen.'"

Sonny Hill hears such talk and shakes his head. He has heard it before. He didn't buy it then; he doesn't buy it now.

For as long as he can remember, the Philadelphia playgrounds teemed with good games and the city's best players.

As a kid, he ran around those courts himself, learning the art of shooting from Philly legend and 12-year NBA vet Guy Rodgers during Around the World games; the love of competition from Rodgers and Temple star Hal Lear, who would jump at the chance to challenge a guy who purportedly dropped 50 points in a pickup game in Camden or Chester; and the grace and beauty of pure talent from his Baptist Church League and high school foe, Wilt Chamberlain.

Hill is credited with starting the first professional summer league in this country, the Charles Baker Memorial League in 1960, answering a call from area pros who wanted to keep their games sharp in the offseason.

Hill turned his own dream into the Sonny Hill Community Involvement League, which housed a college and high school division, then watched his vision spread across the city to other playgrounds, such as 16th and Susquehanna, where the North Central Philadelphia Basketball League took root.

But today even the always optimistic Hill can't help but be a little disillusioned by what he sees in his own city and across the country -- empty playgrounds and "sissy" star players who fear the macadam.

He faults the players, but more he blames the almighty dollar. It was a problem then, when the Baker League fell apart in large part because Bulls forward Gene Banks tore his Achilles and violated his contract by playing there. With today's salaries, it is an even bigger obstacle now.

"Too much money," Hill said. "When I see the game, I don't see the purity of the game, the love of the game, the dedication to the game."

There is, as Ja'Quan Newton learned, so much to lose. Potential scholarships or pocketed salaries outweigh whatever joy an outside game might offer.

Of course, players earned scholarships and salaries back in the day, too.

Yet they played -- all of them. The games moved from Hill's 25th and Dauphin courts outside of the Moylan Rec Center to 16th and Susquehanna, but that didn't stop the city's best from grabbing a game. A who's who put on a show for the hundreds, sometimes nearly 1,000 people who came to watch -- Hank Gathers and Bo Kimble, Doug Overton and Lionel Simmons, Maureece Rice and Cuttino Mobley, Rasheed Wallace and Kyle Lowry.

And now? Hill's high school league is indoors, at Audenried High School. College guys meet at the Hank Gathers Rec Center or McGonigle Hall. The park at 16th and Susquehanna is an overgrown, barren space, the league unable to survive the 2004 passing of organizer Omjasisa Kentu.

Ask city college coaches or former players where to find a good outside game and the answer is a collective shrug. Count Lowry among them.

"I don't even know where you can play outside anymore," Lowry said.

The Raptors guard said he never plays in the playgrounds anymore -- "No, no," he said with a laugh. "That's not what I need to be doing anymore, not as a professional."

The only legit outside run is Rahim Thompson's Chosen League, for high schoolers, and that's only because Thompson practically willed it into existence. A regular spectator at 16th and Susquehanna, Thompson started his league 12 years ago with money out of his own pocket.

On Thursdays, he would cash his check from his job at the parking authority, pay the officials and rent 40 chairs to offer more seating than the half-sawed-off bleacher he had. Even after two robberies forced him out of his home, he kept the league going, packing the scorebook, game clock and his clothes into a 76ers bag and flopping at one friend's house or another until he could take time to find a new home.

Through connections via a part-time job at Slam magazine, he slowly drummed up sponsors, including sports clothing company Mitchell & Ness. Today, with Nike's full backing, he has brand-new backboards, more bleachers and nice uniforms. His all-star players all wear brand-new KDs.

The only thing missing? Most of the city's best players. Eighty-one Division I players have come through the Chosen League, but even as Thompson adjusts his schedule -- he stops games during the open recruiting window in July -- it's getting harder and harder to attract the top names.

"You got these so-called coaches and advisers who don't even have a background in basketball telling kids where to play and not to play," Thompson said. "How can some guy from down the corner tell your kid he shouldn't play outside?

"I get it. AAU is great for exposure, but you get toughness outside. You got the crowd on top of you screaming; you hit the ground hard as crap. So you get inside when there's 2,000 people and it's all air conditioned, and someone starts screaming at you, it's like, are you serious? I just had dudes under the basket talking about my mama."

That's what led Ja'Quan to the Cherashore Playground. He spent three years in the Chosen League and believed it helped turn him into a Philly guard -- a brand of player known for his fearlessness as much as his ability.

Now prepping for Miami, he had to beg his father to let him play in the Chosen Game -- "How do you say no to a kid who just wants to play?" Joe said. But after his fall, Ja'Quan suddenly understood his father's reluctance. "I grew up here, but it's a lot tougher on your body," Ja'Quan said. "When I fell down, man, that hurt. I don't need to be doing that. I don't really think I should be out here anymore."

Follow ESPN College Basketball on Twitter (@ESPNCBB) and like us on Facebook.

Follow ESPN Reader on Twitter: @ESPN_Reader

Join the conversation about "Playground Basketball Is Dying."