A Giant Friendship

San Francisco's most gripping story isn't on the baseball field. It's up in the broadcast booth, where one of the team's most popular and enduring figures is fighting an epic battle ... with a little help.

ONE RECENT AFTERNOON, about three hours before first pitch, Mike Krukow, the San Francisco Giants broadcaster, sat in his condo beneath a ceramic moose, playing an up-tempo version of "Play With Fire," the Rolling Stones classic, on a 98-year-old mandolin. Krukow, a tall man with a full head of silver hair and a permanent air of mischief, was accompanied by his wife of nearly 40 years, Jennifer, and their 29-year-old daughter, Tessa, who strummed a guitar and sang harmonies that carried through the door onto 2nd Street.

Well, you've got your diamonds

And you've got your pretty clothes ...

"Music is my therapy," Krukow said. "Baseball is my life."

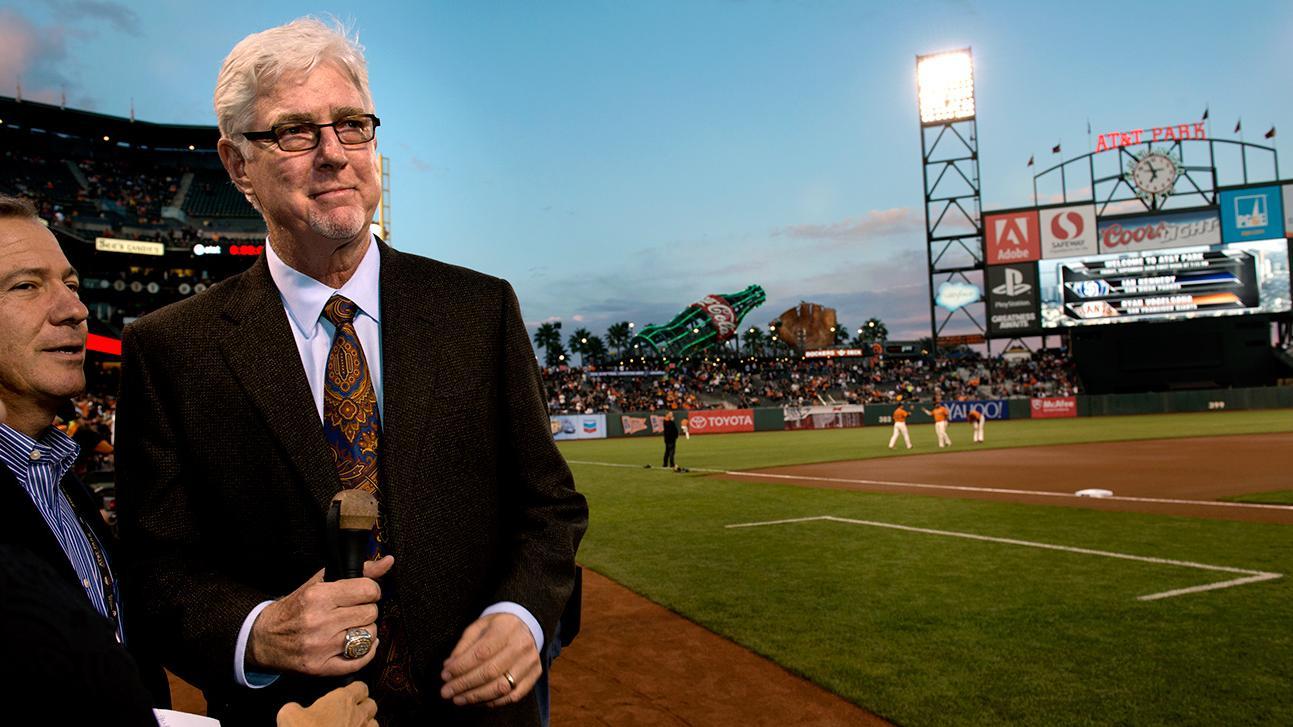

Around 4:30, a golf cart driven by a Giants employee pulled up on the sidewalk. Krukow, who is 62, grabbed a silver REI walking stick and began the short commute to his office -- AT&T Park, a waterfront ballpark that evokes the Disneyland slogan, "The Happiest Place on Earth," except that here Willie Mays is Mickey Mouse. AT&T has a 10-ton mitt and four slides encased in a Coke bottle behind the left-field bleachers and, on the field, a team that's won two of the past four World Series and is headed back to the playoffs Wednesday as a wild-card team. Krukow broadcasts the games on TV with his best friend and former teammate, Duane Kuiper; together they're known as Kruk and Kuip. In recent years, they've become as beloved in San Francisco as the crooked street and are recognized, by many, as the best local broadcasting team in baseball.

Their secret is the same effortless chemistry that characterizes their long friendship: Night after night, they deliver rare insights devoid of pretentiousness, mixed with the kind of whimsical Bay Area humor made famous by Robin Williams.

The two have been inseparable since they met as Giants teammates in 1983. Krukow, a 6-foot-5 right-hander who won 20 games in 1986, had been acquired after a short stint with the Phillies and a long one with the Cubs. Kuiper, who started at second base for the Indians for seven years, was reaching the end of his career. Between Krukow's starts, the two would sit at the end of the bench and perform profanity-laced broadcasts to entertain their teammates. After they took their act into the booth in the early '90s -- a gig that brings them together some 200 days a year -- they continued to hang out during the offseason and to vacation together, with their families.

One typical December morning, Kruk and Kuip spoke by phone around 8. "I talked to him again at noon, and then talked to him again at 5," Kuiper said. "At that point, my wife looked at me and she said, 'Are you guys sleeping together?'"

A good day for Kruk and Kuip comes with a Giants win and at least a half-dozen "horselaughs," as Krukow calls them. These are a reaction to many things: a new catchphrase, a hilarious fan shot on TV, memories.

One year, Kuiper and his wife, Michelle, took up in-line skating. The Giants had an upcoming road trip. "So I tell Mike, "Look, I'm gonna take my Rollerblades to Chicago and we'll go,'" Kuiper said. Krukow, who collects life experiences the way some people collect art, had never in-line skated.

"We're going down Lake Shore Drive," Krukow said. "He's doing figure eights and pirouetting, going backwards. And I don't even know how to stop!" Krukow then made the sound of a man careening out of control: "Ahhhhhhhh....Ahhhhhhhh....."

"He was going round and round, like a helicopter!" Kuiper said. "You know how you see a center fielder going to make a diving catch -- he was that high off the ground. He went down right on his side." Krukow had two cracked ribs.

"The next year, we're going by the same spot, and he had taped it off, like it was homicide!" Krukow said. "A--hole. I was black and blue from my belly button all the way down to my knees, and he tapes off the scene! What a d---. Now every time we go by there it's like, 'Hey, that's the spot where Kruk fell.'"

Dropping into Kruk and Kuip's world -- filled with baseball and music and horselaughs -- you feel as if you want to stay awhile, maybe even move in. But the longer you stay, you see that there are deeper forces at work. And you realize that, as the Giants return to the postseason, their most gripping story isn't on the field. It's up in the broadcast booth, where, with humor and grace, Krukow, one of the most popular and enduring figures in franchise history, is fighting an epic battle that threatens the two things that -- besides his family -- give him more pleasure than anything else in life: playing music and broadcasting San Francisco Giants baseball.

All with a little help from his friend.

Mike Krukow, the color commentator for the San Francisco Giants, is battling a muscle disorder that weakens his arms and legs.

IT STARTED WITH his golf swing, almost 10 years ago, when Krukow was in his early 50s.

For years, Krukow lived near the San Luis Obispo Country Club. In the offseason, with a college buddy, Jon Silverman, he played a form of warp-speed golf they called Michigan Warball. Krukow and Silverman played three balls at a time, betting on every shot, and raced around the course on Krukow's modified golf cart, which "hauled ass" at nearly 30 mph. Krukow would be out the door at 10 and home by lunch. But he began to notice that he had lost about a hundred yards off his drive.

In the manner of most athletes, he blew it off -- not for months but years. As the weakness progressed, people close to him, including Jennifer and the kids, occasionally would ask him what was wrong. "Old ballplayer injuries," he'd shrug. Krukow secretly feared he had amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, Lou Gehrig's disease, "but I didn't want to know. I didn't have the balls." Finally, in 2011, after he could no longer snowboard, he went to the Giants' neurologist, Donald Kitt, who sent him to a neuromuscular specialist, Jonathan Katz (Krukow has two neurologists, Kitt and Katz).

Krukow sat in the waiting room, terrified, surrounded by terminal patients with various stages of ALS. "I'm sitting there thinking to myself: Is this gonna be me?" he said. "I'm sitting there for a while. Your mind goes crazy."

Katz looked at him and said: "I can tell you what you have. You've got a muscle disease. It's not life-threatening."

"I thought I had won the lottery," Krukow said.

“I TALKED TO HIM AGAIN AT NOON, AND THEN TALKED TO HIM AGAIN AT 5. AT THAT POINT, MY WIFE LOOKED AT ME AND SHE SAID, 'ARE YOU GUYS SLEEPING TOGETHER?'”

- DUANE KUIPER

The diagnosis was something called inclusion-body myositis, or IBM, a blandly corporate-sounding disease that, for reasons that are unclear, attacks specific muscle groups, causing them to atrophy. Kitt said he has seen perhaps a half-dozen cases in 26 years of practice. Of the .000008 percent of Americans who get it, most are men older than 50. IBM affects the quadriceps -- the muscles in front of the thighs -- and the flexor muscles around the hands. There's no cure. The disease isn't life-threatening, although it sometimes impedes swallowing in the later stages.

"The funny thing is, it's profoundly sad what's happening with him physically, except when you're around him it's as if it's not happening at all," said Jon Miller, the Giants' Hall of Fame radio voice. "It's only sad when you talk about it with other people. And then you start realizing, 'Geez, it's so sad.' But when you're with him, there's none of that. He's the same as he always was."

Following Krukow around the country with the Giants, from San Francisco to Chicago to Washington to Los Angeles, there's an odd disconnect that occurs. He is battling an insidious disease that, if not fatal, almost certainly will put him in a wheelchair. Yet seemingly he's never been happier. "Look, I'm pissed I can't do a lot of things," he said one afternoon at his condo. "But I gotta really work at being pissed off. Seriously."

Krukow is so relentlessly upbeat it obscures a hard reality: His body is failing him. With some regularity, maybe a couple of times a month, he'll fall "straight down, like a turd from a giraffe." These flash falls are tearing Krukow up. Earlier this year, he stepped off the team bus in the carport at the Ritz Carlton in Denver and collapsed onto his right shoulder, damaging his rotator cuff. Now he can barely lift his arm. During the All-Star break, while moving his family's offseason home from San Luis Obispo, California, to Reno, Nevada, to be closer to his grandchildren, Krukow was standing in the street when he collapsed and found himself on the pavement, alone. "It was like 98 degrees in Reno that day; well, the street was 120," he said. "I'm burning my hands and my knees. I've got a pair of shorts on. It was brutal. Nobody saw that one." It took him five minutes to get up. Later that day, hanging out by the pool, he went down again.

Krukow is acutely aware of where this is headed: "You go from a cane to a walker to whatever you need to do. I'm on the cane process right now."

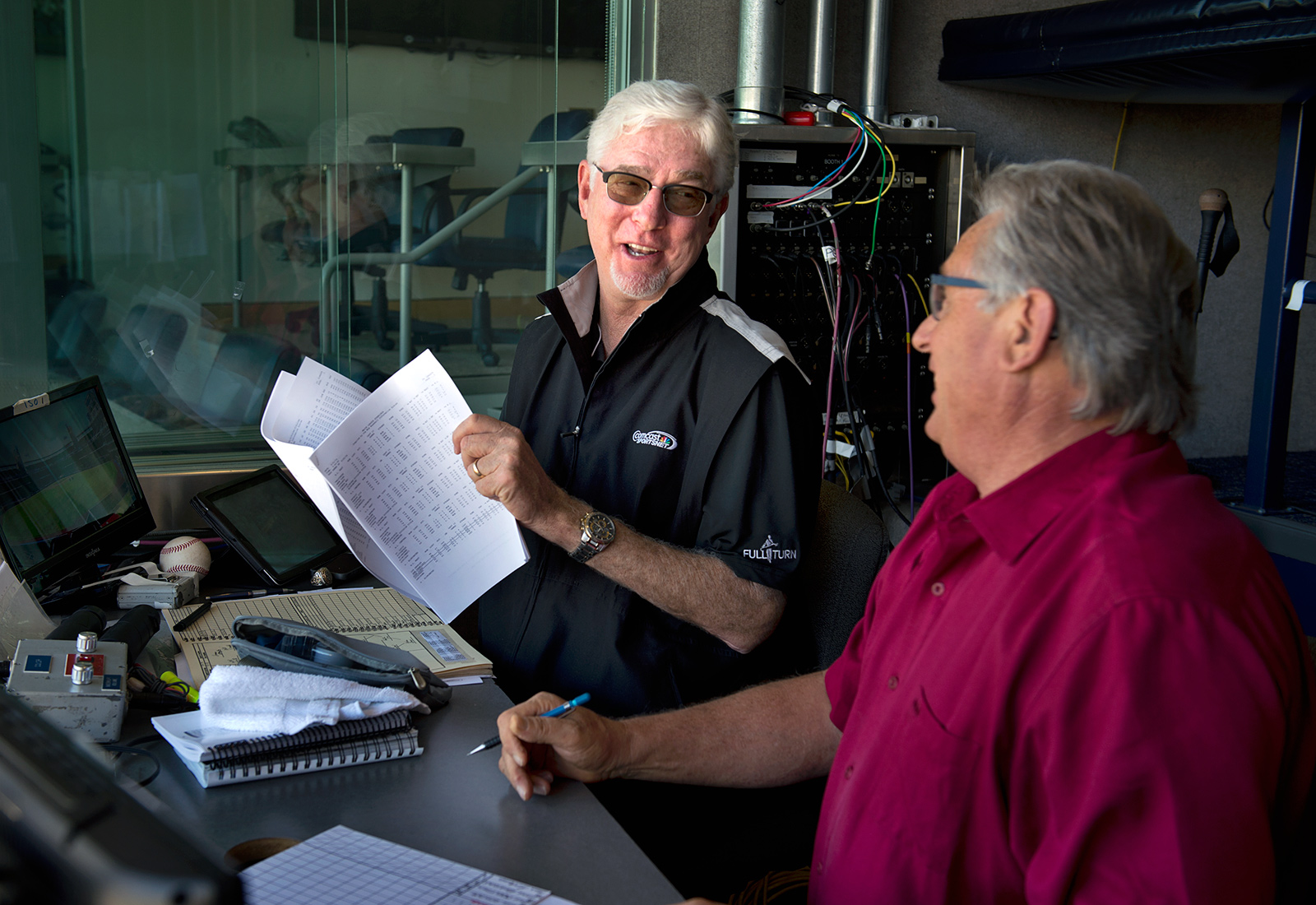

Mike Krukow calls best friend Duane Kuiper his "Sherpa." Deanne Fitzmaurice for ESPN

Kuiper is at his most self-deprecating when he is asked to explain how he is helping his friend. "I don't really do anything," he said. But that isn't remotely true. As Krukow's condition has worsened, Kuiper has quietly taken it upon himself to make sure his partner makes it through the day without taking the kind of catastrophic fall that drives him out of the game. The obstacles that could trip up Krukow are endless -- TV cables, garden hoses, cracks in the sidewalk. Kuiper walks ahead of him, calling out "land mine!" whenever he spots one. "Kuip wants to be the person who makes sure that Mike doesn't just get sick of it and say, 'This is too much,'" said Dave Flemming, Miller's radio partner.

Last offseason, Kuiper arranged for the Giants to alter the broadcast booth at AT&T, installing a railing and replacing the step-up riser with a ramp. Krukow is terrified of being knocked down in crowds, so Kuiper persuaded the team to send the golf cart to shuttle Krukow between the ballpark and his condo before and after games. Krukow's biggest challenge is getting off of the Giants' plane, which unloads on the tarmac. In the routine that they've developed, Kuiper takes Krukow's bags -- including his mandolin -- then walks down the stairs "like he's carrying two pails of milk," said Krukow, who follows.

Because his thigh muscles are so weak, Krukow can no longer descend stairs facing forward. Instead, he turns around and eases himself down like a man slipping into a cold pool.

"Kuip's my Sherpa," Krukow said.

In August, a few days before the Giants traveled to Wrigley Field, Krukow remarked that he might need a cart to navigate the 100-year-old ballpark.

"Already taken care of," said Kuiper, who had made the arrangements three weeks earlier without informing his partner.

The cart was waiting when the team bus pulled up on North Sheffield Avenue. Except for ticket takers and concessionaires, the ballpark was mostly empty and smelled like mildew, fried onions and rain. The cart ferried the broadcasters along the lower concourse and up a ramp, depositing them on the second deck behind home plate. It was another 20 steps up to the press box. "I'll see you up there," Kuiper said. Krukow took the service elevator. There were three more steps down into the visitors' TV booth. Krukow, using his arm strength, gripped the railings and lowered himself down, like a gymnast struggling with a pommel horse.

The booth was cramped, sweltering and crawling with spiders; one fell on the back of Kuiper's neck in midcall. The first night, the skies opened up with the Giants losing 2-0 in the fifth. The Cubs, forever lame, had sent home about half the grounds crew to save money. The remaining crew left part of the infield exposed while rolling out the tarp, then tried to dry it out with leaf blowers. After a four-hour, 34-minute delay, the field was ruled unplayable and the victory awarded to the Cubs. The decision was reversed the next afternoon -- the first time a protest had been upheld in 28 years. But with the game scheduled to resume the next day, it poured again.

Krukow was clearly hurting. On level ground, using his walking stick, he often looks like a prosperous man out for an evening stroll. In fact, he has to "calculate every step. It's like a gas tank: You get depleted. Then you're vulnerable." The second delay lasted about two hours. After hauling himself in and out of the booth for three days, Krukow stood at the top step, peering down anxiously like a man on the edge of a cliff. He never complained, but everyone understood: "I walked out of there pissed at Wrigley," Flemming said.

Kuiper brought Krukow a present to cheer him up: a Zippo lighter embedded with the Chicago Bears insignia.

"I haven't had a Zippo lighter in my hand in 20 years," said Krukow, flipping it open as a hard rain fell over the field.

"I don't buy my wife gifts, I buy you gifts," Kuiper said. "If I tell my wife, she's gonna go, 'Really? Really? You got Kruk a gift?'"

"She thinks we spoon on the road, man," said Krukow, laughing. "She thinks that's true."

text

Deanne Fitzmaurice for ESPN

KRUKOW'S CONDITION BECAME public July 22, in a front-page article in the San Francisco Chronicle by columnist C.W. Nevius, who spotted Krukow leaving AT&T in his cart and asked him what was going on. By then, Krukow's condition was widely known among the Giants and his fellow broadcasters, but he finally agreed to discuss it openly.

For Giants fans, the news was no less of a shock than if they had learned Buster Posey had a career-threatening illness. "These two eternally youthful guys who you figured would be with you your entire life, you suddenly realized, 'Oh my God, they may not be calling games forever,'" said Brian Murphy, a talk show host on the Giants' flagship station, KNBR.

Giants president and chief executive Larry Baer stated the obvious: Kruk and Kuip have become "bigger than most of the players." Their value to the team is incalculable. In 2008, Comcast SportsNet started televising the Giants postgame show, which includes Miller and Flemming and is so informal Kuiper sometimes can be seen eating. Ratings for the show went up 112 percent. The team sells Kruk and Kuip jerseys at its dugout store and holds bobblehead days in their honor, including one this year commemorating Kuiper's lone career homer in 3,754 plate appearances -- the most by any major leaguer with a single home run. (Writer Joe Posnanski, who grew up in Cleveland idolizing Kuiper, flew out for the occasion and marveled for NBCSports.com: "Yes, the Giants and San Francisco fans love him so much, they are giving out bobbleheads of Duane Kuiper wearing an old CLEVELAND INDIANS uniform)."

"At the end of the day, I think they are as important to the team's success as the ballpark," said Corey Busch, the former Giants executive vice president who brought them together in the broadcast booth.

Giants broadcaster Mike Krukow explains why music is such an important part of his life.

WATCHING BASEBALL WITH Kruk and Kuip is like sitting at a neighborhood bar with two best friends who happen to be hilarious ex-players and want nothing more than for you to enjoy the experience as much as they do. The two could hardly be more different. Krukow, the analyst, grew up in Pasadena, the son of a captain in the Los Angeles County Sheriff's Department. Even now, he has the fidgety restlessness of a teenager. During games, Krukow grips a baseball (swapped out when the Giants lose), which he says calms him like a "5 ounce Quaalude." He occasionally fumbles it onto the hollow floor, making it sound as if a grenade has been dropped in the broadcast booth. Kuiper cranks out wry observations in the smooth baritone he inherited from his father, a Wisconsin dairy and cattle farmer who moonlighted as an auctioneer (As a kid, Kuiper would shout "yep!" and "over here!" while his father practiced in the barn). Kuiper is so laid-back and laconic, particularly when slouching over the mike during the postgame show, you could picture him with a cigarette and a tumbler of scotch, hanging out with the Rat Pack (Kuiper quit smoking years ago, but as a player, to amuse his teammates, he would sit frozen on the team plane with a Vantage between his lips and his Zippo lighter cocked, waiting for the no smoking sign to go out). Kuiper sometimes answers to "Smoothie," a nickname he claims to have given himself one day while filling out a Giants questionnaire.

Kruk and Kuip have their own patois and ever-expanding vocabulary, drawn from their playing days, life experiences and whatever pops into their heads. These "Krukisms" have been widely anthologized and often end up on T-shirts sold outside the park. Several years ago, the camera panned to a group of women, whom Krukow referred to as "Gamer Babes." There are now several Bay Area Gamer Babe chapters; Napa Valley's has 300 members who walk in parades and raise money for charity. (A pregnant woman recently showed up at AT&T with a "Future Gamer Babe" T-shirt stretched over her stomach). In 2010, as the Giants ripped off one excruciating win after another en route to their first world championship since 1954, Kuiper closed out a broadcast by sighing: "Giants baseball ... Torture." Soon signs started sprouting up around the ballpark.

"Uh, where are you guys going with this?" Staci Slaughter, the Giants' senior VP for communications, asked Kuiper one day. She was understandably skeptical about a marketing slogan suggestive of Abu Ghraib.

It was too late. "Torture" became the rallying cry of the entire historic season. "If we had any brains at all, we'd think this stuff up and copyright it. But that's no fun!" Kuiper said. Krukow likes to use the telestrator to "eliminate" people, drawing an X through Dodgers fans, any appearance by Tommy Lasorda, "tools" who won't give foul balls to their dates and so on. The gag became so popular Comcast sold advertising around it. That ruined it. "When you start to force it, it doesn't work," Krukow said. His signature strikeout call -- "Grab some pine, Meat" -- is an extension of his playing career, when all rookies were called "Meat," and conversations around the house.

"He's called me Meat since I was a little kid," said his son Baker, a 31-year-old salesman for an electrical supplies company. "I didn't even know my name was Bake until I was 10."

For many fans, the thrill of watching Kruk and Kuip is waiting to hear what comes out of their mouths. This is especially true of Krukow. In 2012, centerfielder Angel Pagan fouled a pitch off his crotch and collapsed, writhing. "That's a massageless injury," Krukow explained. Once, describing 6-foot-10 pitcher Randy Johnson, he said on the air: "You know why he's called the Big Unit? Because he has a big unit." Every season, Krukow is good for at least three or four over-the-top rants that create local headlines. During the Wrigley Field flood, he accused the Cubs of "premeditated" sabotage to get a rain-shortened win. (He later retracted the charge after Miller, who was doing TV that night, chided him: "You can't make an accusation. You don't know.") In 2007, Krukow called Curt Schilling a "horse's ass" after Schilling criticized Barry Bonds over his steroid use.

Occasionally things get lost in translation. Krukow's expression for a pitcher who mindlessly chucks fastballs is: "Brain Dead Heaver." One indignant viewer asked how he could be so insensitive as to call a major leaguer a "Brain Dead Hebrew."

"We're all getting fired, all of us!" Krukow will occasionally tell Jim Lynch, who has directed Giants broadcasts since 1987.

"You're untouchable, dude! You can say whatever you want," Lynch replies.

Kruk and Kuip's range extends from the arcane to the absurd.

During one typical three-inning stretch at Denver's Coors Field recently, they discussed the effect of the altitude on Sergio Romo's slider; a double-play grounder that was botched by the arc of the shortstop's toss; the old Clint Eastwood version of "Paint Your Wagon"; and the lyrical sound of Colorado left-hander Yohan Flande's name.

"I am Yo-han Flandaaay, hairstylist to the stars," Krukow ad-libbed, in an accent that sounded vaguely French.

More than anything, Krukow and Kuiper seem determined to not allow Krukow's affliction to get in the way of a good horselaugh. When they first started, at Candlestick Park, they routinely shoveled paper out of the window and let the jet stream carry it into the visitors' broadcast booth. When Flemming, who's a quarter-century their junior, first broke in, they hazed him mercilessly. They called him Phlegm or Phlegmlord -- unfortunate nicknames for a radio announcer. Then, after someone referred to the Giants broadcast team in a letter to the editor as: "Krukow, Kuiper, Miller, et al.," they started calling him "Et Al." Back then, Flemming toted around a comically large roller bag, so Kruk and Kuip stuffed it with a watermelon and a 12-pack of Diet Coke one day, then sat back and howled as Flemming wrestled it off of the ground and cracked it open.

"They'd talk about me on the air," said Flemming, laughing. "But in a subtle way it told the audience that I was part of the team. I was somebody who could be trusted. I was their friend. It was definitely on purpose."

One warm evening recently, as the Giants played in Washington, D.C., Krukow stared out at the field. The Nationals were staging one of those absurd races in which people wearing big-headed costumes -- sausages, Hall of Famers, whatever -- circle the field. In D.C., naturally, it's dead presidents, and Krukow looked on, bemused, as Washington, Lincoln, Jefferson and Teddy Roosevelt scampered by.

He was curious about the fifth participant, who seemed out of place.

"Why Taft?" he asked Kuiper. Smiling, Krukow grabbed his walking stick, carefully avoiding the land mines, and ambled off to the bathroom.

Kuiper chuckled and removed his headset.

"Can you believe they pay us for this?" he said.

text

Deanne Fitzmaurice for ESPN

JENNIFER KRUKOW HAS noticed that, before IBM robs her husband of his favorite activities, he attacks those activities with even more intensity, trying to squeeze out every last ounce of enjoyment before it's gone.

Lately, Krukow has been playing music night and day. He recently bought two $4,000 mandolins -- one for himself, with the Giants logo inlaid on the headstock in mother of pearl, the other for Jennifer's birthday, inscribed with her name. Krukow keeps his mandolin within arm's reach of their bed. "There are nights when I can't sleep, and I'll just pick it up, start playing," he said. "It is relaxing, it's incredibly relaxing. You don't think about anything else but playing that thing. It's like playing golf. When you play golf, you don't think about anything, right? When you're swimming, you're only thinking about your stroke. I can't do those things anymore. So really this has become more important to me."

Strewn around Krukow's condo are about a dozen guitars, mandolins, banjos, bongos and even a ruan, a Chinese string instrument Krukow picked up in Chinatown. All the Krukows -- Mike and Jennifer, their four boys, and Tess -- play instruments; every family get-together is a jamboree. For years, the Krukows have tossed around potential group names: The Special K's, the Tools of Ignorance ... "There's another one," said Tess, laughing and slightly embarrassed as she held the guitar. "Only it's not really appropriate. My dad came up with it."

"Dad's Sperm Trio," Krukow said.

“WHEN YOU SEE SOMEONE WHO HAS LIVED EVERY DAY TO ITS FULLEST AND GETS THE

BEST OUT OF PEOPLE, AND THE BEST

OUT OF THEMSELVES -- THAT ENERGY, THAT LIFE --

HE HAS THAT. THAT'S WHAT

I ASPIRE

TO BE.”

- WESTON KRUKOW, SON

Krukow takes his mandolin on Giants road trips and spends afternoons in his hotel room, playing it and watching the Food Network. "He just knows that his time is short," Jennifer said. "There are times I don't want to listen to the banjo, really loud, and I'll say, 'Honey, I don't know if I can take that right now.' And then I feel really bad about that because I understand. He has said this at times: He doesn't know how long he has to play."

Krukow can't play as long as he used to because his fingers become weak. His youngest son, Weston, said he has noticed that Krukow "has become obsessed with drums. He's playing the drums in a really wonderful way, and the muscles you use for that are different. He's gonna be fine. He'll never stop playing." Weston, a dancer with San Francisco's Smuin Ballet, said he and his father sometimes watch games together and compare and contrast the movements required of their respective professions. Krukow, while he sleeps, sometimes dreams up dinners he wants to cook or songs he wants to play. Once he dreamed up a dance routine about a boy who starts out performing to a lushly stringed version of Beethoven's Ninth, then pulls an air guitar from a case and dances to a rock version of the same symphony. Weston later staged the routine in Iowa with one of his students.

Weston said he idolizes his dad. "When you see someone who has lived every day to its fullest and gets the best out of people, and the best out of themselves -- that energy, that life -- he has that," Weston said. "That's what I aspire to be."

Krukow's biggest fear is that he'll become so impaired he'll become a burden to the Giants. More than in any other sport, the travel required by Major League Baseball is relentless -- a seven-month, 45,000-mile circus of buses, planes and luxury hotels. "It's a herd, and you gotta keep moving," Krukow said. "You don't want to stand out because of special needs." The fall coming off the bus in Denver was as embarrassing as it was painful because it happened in front of the team. Krukow and Kuiper were both shaken: It was a terrifying glimpse into a future neither is eager to face. Kuiper was especially upset because he had walked ahead and wasn't able to prevent it. That night, Kuiper called his younger brother Jeff, who produces the Giants broadcasts for Comcast. If and when Krukow can't travel anymore, Kuiper wanted to know, was it possible for them to do the games from different cities -- Krukow in San Francisco and Kuiper on the road?

"I've been thinking a lot about this," Jeff said. A third Kuiper brother, Glen, the youngest, broadcasts the A's on Comcast. They all consider Krukow their fourth brother. "I don't see why not," Jeff told Duane.

Krukow was nursing his wounds in his room. Kuiper told him what Jeff had said.

"I felt better," Krukow said.

For their part, the Giants have told Krukow they'll do anything to make it work. "I view it this way: Mike is part of the soul of this franchise, and he and Duane will be the soul of the franchise, quite frankly, as long as they've got a pulse, as long as they're breathing," said Baer, the CEO. "As long as he wants to go, we'll do whatever we can to accommodate him."

Krukow says he thinks he has several more years in him, but of course nobody knows. He and Kuiper don't much talk about it. Doing so would force Krukow to dwell on it, which is basically the opposite of what he wants to do, the opposite of a horselaugh.

"We gotta keep him around," Kuiper said. "I'm not ready to break in another guy."

Steve Fainaru is a senior writer for ESPN. Follow him on Twitter (@SteveFainaru).

Follow ESPN Reader on Twitter: @ESPN_Reader.

Join the conversation about "A Giant Friendship."

text

Deanne Fitzmaurice for ESPN