Do you know Mike Krzyzewski?

His friends, family and the people closest to him say you know the coach -- not the man.

CHICAGO -- You think you know Mike Krzyzewski, don't you?

After watching him prowl the Duke sideline for more than 34 years, with his jet-black hair combed just so, you've got him pegged.

Look how he stares at the officials, his body language practically dripping with condescending superiority. Or how about the stares -- the ones that could wither concrete -- that he turns on his players?

He's so structured, so damned rigid. He must have been fun as a child; probably doesn't have a playful gene in his body.

And what of all that success as a head coach? He's won four national championships, and then, when the Dream Team was as good as gone, led Team USA to two Olympic gold medals. Sunday he could claim his 1,000th college win against St. John's at Madison Square Garden.

That can happen only if a man is obsessed, so consumed by his job there's no room for a hobby or even a life, right?

That's Mike Krzyzewski, a stiff, superior, stone-faced cyborg.

"Mickey? He's just one of us," says Ed Stanislawski, calling Krzyzewski by the childhood name his oldest friends still use. "He was, he is, a regular guy."

Stanislawski, "Stas" to his buddies, is sitting at a table on a recent Sunday afternoon at the White Eagle, a restaurant and banquet hall that has been catering to Chicago's Polish community for more than 65 years. He's been asked here with some of his childhood friends to help chip away at the icon, to explain why people who think they know Mike Krzyzewski really don't know him at all.

Who he is -- truly is -- is so much simpler, yet so much more interesting, than the image.

For instance, he once fancied himself a pro wrestler. He loves to pop Bubble Wrap. He can't dance, but he can garden now. He offended his future wife on a date early on, but is a well-intentioned, if not always perfect, parent and husband.

And as hard as it is to imagine now, he once worried he wouldn't be given enough time to prove he could actually coach.

OK, yes, he counts the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff as a friend, but he also still seeks the counsel of his high school geometry teacher.

Is that the guy you thought you knew?

"He's not nearly as interesting,'' jokes another friend, Dennis Wrobel, "as [the world makes] him out to be.''

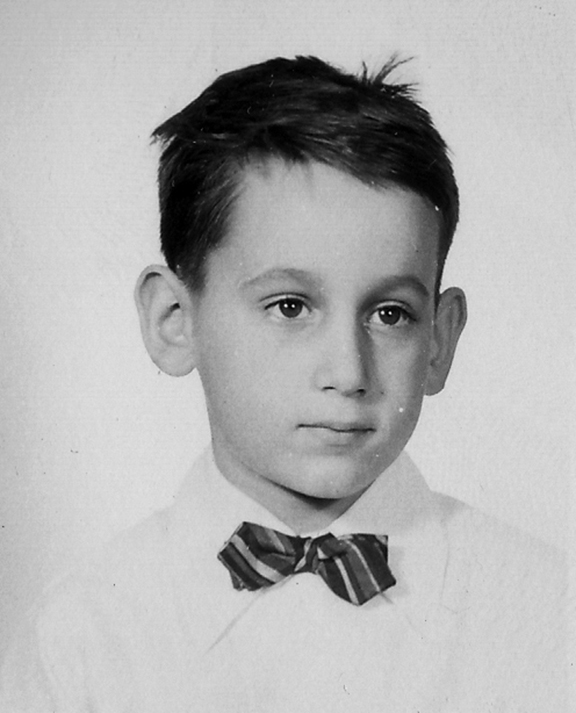

As a boy, Krzyzewski was nothing more or less than a long-legged kid from West Cortez Street. Courtesy Duke University

WHEN KRZYZEWSKI WAS a kid, sports meant everything to the neighborhood boys and practically nothing to their parents.

Their parents didn't have time for such frivolity. They were too busy working -- like William Krzyzewski, Mike's dad, who spent nearly 25 years as an elevator operator before trying his hand at owning a bar, and his wife, Emily, who each night headed to the corner of Damen Ave. and West Augusta Boulevard, where she'd catch a downtown bus to her job cleaning at the Chicago Athletic Club.

If you wanted a ballgame, you grabbed some buddies and headed for the playgrounds. Some kids got fancy -- Krzyzewski's buddies nicknamed their playground squad the Warriors, for example -- but parents had no time and certainly no money for schedules and practices and uniforms and coaches.

St. Helen School, the neighborhood elementary, didn't even have a gym, much less fund any teams.

So when the boys begged school administrators to help them join the local Catholic Youth Organization basketball league, their pleas fell on deaf ears.

Undeterred, one boy, a seventh-grader, took it upon himself to organize his buddies into a team. He served as player/coach.

Yep.

Krzyzewski.

"We were pretty good, too," Dennis "Moe" Mlynski says.

Maybe the kids should have seen it, how a boy savvy enough to lead his peers, a preteen brazen enough to organize a team, was destined to be a coach.

Except they weren't looking, and even if they were, Mick Krzyzewski didn't seem so extraordinary. Krzyzewski was a crossing guard; some other kids were altar boys. He leaned toward basketball; others excelled at baseball. He was nothing more and nothing less than the long-legged, younger Krzyzewski boy from over on West Cortez Street.

Sure, he was competitive, but they all were. What's the use in playing a game unless you choose up sides, and why choose up sides if you weren't going to try to win?

He played just like they did -- hustling outside first thing in the morning during the summer days and right after dismissal during the school year to the Columbus Elementary School playground or the nearby social center, where Mr. Eaton, the center director, would make sure they kept active when it was too hot to play outside.

Pro wrestling was popular among the boys, and they liked to imagine themselves as stars of the ring. Krzyzewski was partial to Edouard Carpentier, who excelled at a maneuver called the rope-aided twisting headscissor. He and Wrobel formed one tandem, called themselves the Flying Fortresses. Together they'd battle their nemeses, Tom "Porky" Stepek and another boy, who competed under the alter egos Exquiso and Supremo.

"We even made up championship belts," Stepek says.

When the weather got too unbearable, the boys would head to the lakeshore, where they'd fashion their beach towels into turbans and call themselves sheikhs. Whichever boys didn't join in, well, they were the enemies -- the city slickers -- and it was a day full of games featuring the sheikhs versus the city slickers.

We should probably stop here and imagine this for a second: Mike Krzyzewski with a towel turban on his head. Coach K putting a half nelson on a buddy, calling himself a Flying Fortress.

"Why is that funny?" Stanislawski asks. "It's what we all did. We just had fun -- good, clean fun."

It's probably not hard to imagine now, but Krzyzewski was something of a teacher's pet. He got good grades and was well liked by his peers and by the nuns who taught at St. Helen.

"Oh, he was a brown nose," Vivian Kolpak says with a smirk.

Kolpak, whose family owns the White Eagle, is the requisite girl every pack of boys seems to have, more little sister than paramour.

"Mickey? He's just one of us. He was, he is, a regular guy."

- Ed Stanislawski

She demurs for all of 15 seconds when asked to tell tales about Krzyzewski, then grabs a chair and joins right in.

The stories, passed along with the pierogies and potato pancakes at the White Eagle, carry with them the idyllic whiff of nostalgia. Stories of a multiplication contest in which ultracompetitive-but-impatient Krzyzewski completed his first but made so many mistakes he lost the coveted Sacred Heart trophy to Kolpak; of Sister Lucinda, the seventh-grade teacher, who gave everyone dashes in the conduct portion of their report course because, as Kolpak remembers, "We were so bad, we didn't even earn an F. Not bad bad. We all got straight A's, but we fooled around, passing notes and talking in the back of the room."

A lifetime has passed since those innocent days -- marriages and deaths and children and grandchildren. They've all done well for themselves. Wrobel is a retired mechanical engineer, Stepek a former accountant. Mlynski still works as a financial controller, and Stanislawski is a risk manager.

No one can match the finances or fame of Krzyzewski.

And they don't care. There's not a hint of jealousy or animosity among them.

They are enormously proud of him, but not because of what he has accomplished. They're proud of who he is.

"You know, one serious thing I will say," Kolpak says, "he kept that name, and that means a lot to people here. I don't think Mick realizes, I really don't think he has a clue, how proud our families were -- all the Poles in Chicago, really."

Duke coach Mike Krzyzewski looks back at his team's loss to Virginia in the 1983 ACC tournament, a day he claims was pivotal in his career.

THE FUNNY THING about that name: Krzyzewski's own father didn't use it. He went by Bill Kross, hoping to avoid the sting of discrimination that might come with being the son of a Polish immigrant.

William Krzyzewski was like most fathers in the neighborhood: firm, strict and distant. The neighborhood boys, who can recall their childhood with such ease, have only vague memories of Krzyzewski's father -- that he made his boys clean up at the bar, expected them to behave and loved a strong cup of coffee.

"My aunt [Emily] didn't make it quite the way he liked it," says Dan Klemanovic, a young cousin on Krzyzewski's mother's side, "so every night, he went out for his own."

Emily Krzyzewski was famous for her chocolate chip cookies, and Mlynski remembers the half-gallon of ice cream she served with every meal.

Her family also is responsible for that jet-black hair.

"My uncle Walter and some of our cousins had that same hair," Klemanovic says when the question of Krzyzewski's non-graying hair is brought up at the White Eagle. "I think it could be the genes."

Let's just say not everyone at the table agrees.

The Krzyzewskis rented the bottom half of the house on West Cortez, with an aunt, uncle and cousins upstairs. On holidays and most weekends, the extended family got together for dinner; Klemanovic remembers rousing New Year's parties in one great-uncle's basement.

Times were tough yet simple, Krzyzewski's parents less formally educated but plenty wise.

"I remember when we were going to high school for the first time," Mlynski says. "We had to take a bus, and his mother said, 'Make sure you get on the right bus.' And he's, of course, like, 'Mom, I know what damned bus to take.' She said, 'No, I mean you get on the right bus in your life, that you surround yourself with good people.'"

text

The ordered and disciplined lifestyle of the U.S. Military Academy appealed to the young Krzyzewski, here with Bob Knight (left). ESPN Illustration/USMA

IF EVER A MAN seemed predestined for the order, discipline and general uptightness of the U.S. Military Academy, it would seem to be Krzyzewski.

Mlynski remembers the day his best buddy told him of his college plans. They were sitting on the dip in the black, wrought-iron railing along the Leavitt Street sidewalk outside of Mlynski's home. Mlynski was stunned. Kids didn't leave the area to go to college then, and certainly not to go to military school.

Krzyzewski wasn't sure about the decision, either. His parents were sure of it; they saw it as an opportunity he couldn't pass up, one with a charted future and a lifetime of connections.

Him? Not so much. Then again, kids, even the most confident ones, weren't sure about much back then. The Vietnam War was raging, and teenagers, stuck between their parents' old-world beliefs and the vibrant, freer world opening before them, had plenty of questions.

And Krzyzewski, the man who seems to have all the answers now, didn't have any. Just like any teenager, he needed guidance and support, or at least someone to listen.

He needed Father Francis Rog.

A geometry teacher at Krzyzewski's high school, the all-boys Archbishop Weber, Rog was demanding yet engaging. He pushed his students hard -- they not only finished the ninth-grade geometry text but most of the sophomore and junior curriculum, too -- but he also allowed them to needle him, even prank him on occasion.

Once Krzyzewski's class placed an apple on Rog's desk, hoping to curry favor with him. Rog ignored it for the entirety of the period and then, just before dismissal, suggested the class might want to do a little better to try to win his affection.

"The next day," says Rog, now wheelchair-bound but still clear-minded, "the whole desk was topped with all kinds of fruits and vegetables, including a pumpkin."

He remembers Krzyzewski as both unique and typical. He seemed a little wiser, maybe even a touch more mature, than his peers, yet he shared the same worries. Often he'd seek out his teacher after school, the two meeting at a cafeteria table to talk. Rog won't say what troubled Krzyzewski except to say that he was a "very, very normal teenage boy."

Krzyzewski is the counselor now. He guides players on the basketball court and coaches them off of it, too. He has penned books on leadership -- "Leading With the Heart" and "The Gold Standard: Building a World-Class Team" -- and is paid to speak to corporations and civic groups.

Yet he's also still that young boy, the one who doesn't have all the answers and who needs a sounding board.

Father Rog is still that sounding board.

When Krzyzewski's mother died in 1996, he asked Father Rog to celebrate the funeral Mass; and when a devastated Krzyzewski had to bury his older brother in December 2013, he again turned to his teacher, mentor and friend.

Krzyzewski calls frequently -- most recently in October to apologize in advance for not being able to make Rog's annual birthday celebration because it's in January and, well, that's a tough time for him.

"Of course he can't make it," Rog says, laughing.

Coach K visits when he can and sends trinkets when he can't. Midway through an hourlong visit in a little conference room at the nursing home where Rog lives, the priest pushes up the sleeve on his cardigan sweater to reveal a watch -- a Duke watch, a gift from his old pupil. In his room, there is a collection of Duke polo shirts.

"The gifts he sends, they're instances of respect," Rog says, "because I'm a fan, but not of the sport, per se. I'm a fan of the person."

The day Krzyzewski graduated in 1969 from West Point, Mike and Mickie were married in the chapel on campus. Courtesy Duke University

THE FIRST TIME Carol "Mickie" Marsh went on a formal date with her future husband, he pissed her off, pissed her off royally.

They'd been out before. Once, he had an extra ticket to a Martha and the Vandellas concert at the Whisky a Go Go, and she really wanted to see the band.

This time, it was a little more formal, more official. Krzyzewski had written from West Point that he would be home soon on leave and asked whether she would like to go to a Chicago Bears exhibition game. Mickie was a pretty girl with a glamorous job as a flight attendant, and no shortage of suitors, but she gladly accepted the invitation.

"He picks me up and he tells me that I was his third choice for a date that night," Mickie says. "I was so pissed. So pissed. I was that cocky. How could I be someone's third choice? And why did he tell me that? What advantage did he gain?

"He just said things you weren't supposed to say. He was different."

Luckily for Krzyzewski, often enough the oddball approach worked. He once sent Mickie nine yellow roses, figuring anyone could send six or a dozen. This intrigued her -- and helped her get over her initial hostility at being the bronze-medal date winner.

Mickie took Krzyzewski's blunt assessment as a challenge.

Third choice, huh?

That was never going to happen again.

"He picks me up and he tells me that I was his third choice for a date that night."

- Carol 'Mickie' Kryzyzewski

It didn't, either. On the day Krzyzewski graduated from West Point in 1969, Mike and Mickie were married in the chapel on campus.

All these years later, she understands him so well that nothing surprises her.

Mickie Krzyzewski knows what you think of her husband, or at least who you think he is. And on some points, she won't argue.

The laser focus -- yeah, that's legit. In the summer, he revels in the complete chaos of beach vacations with all the grandkids, but he's never "off" entirely, in part because of the demands of being Mike Krzyzewski but also because of the genetic makeup of Mike Krzyzewski.

But this notion that he is nothing more than some sort of basketball shut-in, a mad scientist who has locked himself away from any and all other outside involvement?

No, Mickie says, there you couldn't be further from the truth.

Just check out her kitchen. Krzyzewski has office space in their Durham home, upstairs and away from the noise and commotion of daily living. It's filled with stuff -- junk and doodads and collections; Mike's Warehouse, Mickie jokingly calls it -- but not office stuff because the office is not his office.

He works in the breakfast nook off the kitchen. Well, what was once the breakfast nook, anyway. There's a table, but not for eating -- "We eat at the counter," Mickie says. The table is strewn with papers and notes, and the TV is for breaking down game tapes, not watching the news.

"He doesn't like to be upstairs by himself," Mickie says. "He has to do all this stuff, but he wants to be where I am. He doesn't want to be isolated."

HERE'S A THING that few completely understand about Mike Krzyzewski: what drives him.

A need to be the best, right?

Well, yes and no.

Yes, Krzyzewski wants to win and succeed, but it's not because he wants you to laud him and love him.

His motivation is entirely personal and relatively unchanged from his days as a kid in the Chicago playgrounds -- if you're going to play a game, you choose up sides, and if you choose up sides, you're going to try to win.

The Krzyzewskis don't sit around counting wins -- how many until that 1,000th, dear?

"Our lives always seem to be added up to some number," Mickie says, "but that number doesn't add up to our lives."

Duke coach Mike Krzyzewski, family members and former players look back at the 1995 back injury that took him away from the game for a time.

KRZYZEWSKI TOOK A graduate assistant job at Indiana with his old college coach because he loved basketball and had an inkling that he'd like coaching.

He took a head-coaching job at his alma mater because he loved basketball, and by then the inkling was a full-fledged calling; he knew he wanted to coach.

He took a head-coaching job at Duke because he loved basketball, and the calling became a passion; he thought he could be a pretty good coach.

And then, of course, he wasn't.

That's the part people forget all the time. All those NCAA tournament appearances, shining moments and gold-medal moments can blind you that way, make you forget that Mike Krzyzewski was not as successful as a basketball coach for a period of time.

The man who seemingly has won since the day he was born -- twice leading scorer in Chicago's Catholic league as a high schooler, and two NIT berths in college (back when that tourney outshone the NCAA tournament) -- was 38-47 in his first three years at Duke. Fans, already convinced that athletic director Tom Butters had lost his mind when he hired the Army coach with the unpronounceable name, were more than ready to ask Krzyzewski to hit the (Tobacco) Road.

Gen. Martin E. Dempsey was a Duke graduate student around that time. He, too, was an Army graduate and, though a few years younger than Krzyzewski, figured his fellow West Pointer could use a little help.

"So I wandered over into Cameron," Dempsey says. "In those days, you could do that -- walk into his office without whatever biometric screening you need today. I think maybe that day the school paper, the Chronicle, suggested he be hung in effigy. Anyway, I introduced myself and told him I'd be glad to help mentor a few players if he wanted to send them my way."

And he did. Krzyzewski, the man who would later coach LeBron and Laettner, Jabari and Jahlil, wanted help.

"He had a plan and a system, and he knew what he wanted to accomplish," Dempsey says. "He was just worried he wouldn't have enough time."

More than 25 years later, Dempsey was working for the Army as the director for leadership development. He needed a speaker.

He got Krzyzewski.

Now the two are among the most decorated in their fields. Dempsey is in the fourth year of his appointment as the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff; Krzyzewski is the greatest coach of his generation.

They take turns speaking to each other's constituents, Dempsey to the Duke and USA basketball teams, Krzyzewski to Army leaders.

"He's a brilliant public speaker, and I don't throw that word around very often," Dempsey says. "He's got the credibility, of course, and he's persuasive. But what sets him apart is he's personal. He's a very accomplished person but a very normal person."

text

Krzyzewski patrols the sideline during a 1986 game against the Tar Heels. ESPN Illustration/USA TODAY Sports

EVEN AFTER ALL of that, you need proof, don't you? A few kind words and a couple of anecdotes from some old buddies aren't enough to make you a believer.

That's understandable.

OK, picture this: Mike Kzyzewski pretending he's one of the Temptations, trying to mimic their famous dance moves in his living room.

Can you see it -- a tiny apartment room, a scratchy record playing, maybe, "Ain't Too Proud to Beg," and Krzyzewski trying to shuffle around his living room in a '70s version of a line dance?

Of course you can't.

Mike McGovern can. He lived it regularly. When Krzyzewski was married and living in Virginia, his wife would go out to run an errand, leaving him home with their toddler daughter, Debbie. Krzyzewski would phone up McGovern, an old college roommate, and the two would spin some records -- always Motown, frequently the Temptations -- to entertain themselves and maybe placate Debbie.

"And then we'd try to do the steps like the Temptations," McGovern says.

"He can't dance. Not at all. He thinks he can. He thinks he can do anything, but he cannot dance. Ask him. Ask him to show you his Motown moves. That will be good."

"That's true," Mlynski agrees when news of Krzyzewski's rhythm imbalance is relayed back to the gang at the White Eagle. "He can't."

"What?" Stanislawski adds wryly. "He and Fred Astaire are one and the same.''

So there you go. The man has two left feet (and perhaps a webbed toe, but let's not go there).

But hell, maybe we need to spill some secrets to make you see that Krzyzewski is actually more normal than he's cracked up to be.

He's a lousy driver -- woefully impatient.

"He's just as serious as you could be, very matter-of-fact, and he says to me, 'That's the only way I can serve my country.'"

- Gerry Brown

"We took a ride to his house and some poor guy is making a left turn, but not fast enough for Mick," Mlynski says. "He's laying on the horn. 'C'mon. C'mon.'"

He's useless around the house. Years ago, Mlynski, who spent some time as an apprentice making stained glass, went to Durham to hang a few pieces in the Krzyzewski home. He needed a screwdriver and went to the garage to grab the toolbox.

"There wasn't a damned tool in there," Mlynski says. "Maybe a ruler."

Krzyzewski does, however, like to putter in the garden. These days, he's not bad at it, but when he started? Heavens.

"Well, we had a little duplex and we lived on the end unit," Mickie Krzyzewski remembers. "There was a little side yard. It couldn't have been more than a few feet to the fence, but remember, he grew up in the city. He had an alley, so what did he know? But he was determined that we'd have a garden, and the first thing he planted? Corn."

Yeah, there was no corn on the cob that year.

Years later, when he got a little better at the gardening thing, he shoved a rake onto the seat of the first fancy car he ever purchased as a head coach at Duke.

His administrative assistant, Gerry Brown, was apoplectic. Why on earth ...? "He'd go around campus and rake up the pine straw and put it in the trunk to use at his garden," she says. "I'm like, 'You have this beautiful car, and you're putting a rake in the front seat and pine needles in the trunk?'"

As you might guess, lots of people send lots of things to the Duke basketball offices -- gifts for Krzyzewski to keep, mementos they'd like to be signed. They take care of their prized possessions, wrapping them in Bubble Wrap to keep them safe.

"He'd take the sheet out of the box and go down the hall popping," Brown says. "Some kids put it on the floor and stomp on it. He won't do that. He's just walking down the hall, pop, pop, pop. Now when I open a box, I take that stuff out.'

God, reading that makes you feel better, doesn't it?

The man has some good old-fashioned flaws and even a few quirky habits.

Who doesn't like to pop Bubble Wrap?

One more: So imagine you're one of Krzyzewski's three daughters and you want to bring a boy home to meet ... him. Once, many years ago, Debbie had a crush on a boy whom her mother deemed "horrible." Krzyzewski was ready to do what dads do best -- forbid her to see him -- but Mickie figured that would only push the two closer, star-crossed lovers and whatnot. Instead, she suggested, let's invite him to the house so Debbie could see exactly why he doesn't fit in.

"So Michael thinks that's a great philosophy," Mickie says. "And he says to Debbie, 'OK, invite so-and-so over to the house this weekend.' And she's all, 'Oh Daddy, thank you, thank you.' Then he says, 'But he can't sit on any of the furniture.' I just put my face in my hands. What do you do with that? She's crying, and he's looking at me like, 'What? What did I do?' The boy never did come over."

That's not the world's greatest living college basketball coach. That's every dad in America, dealing with a mortified teenage daughter while his wife figuratively slaps her hand to her forehead.

Except here are a few other things you need to know:

When McGovern, his Temptations partner, got married, Krzyzewski's gift was two tickets to the ACC tournament for as long as he remained Duke's head coach.

Yes, he loves flowers, but he's especially partial to red poinsettias. They were his mother's favorite, and during the holidays he nearly floods the Duke basketball office with them.

Each month he mails at least 10 handwritten birthday notes to every single basketball player on the team mailing list -- "I don't even address them," Brown says. "He just puts them on my desk to be mailed."

One of his first great Army basketball players, Robert Brown, is now a three-star general. During his decorated career, he served as the deputy commanding general in Iraq. A few years ago, an Air Force plane scheduled to deliver 5,000 holiday stockings to the troops was diverted and the stockings were stuck stateside. FedEx wanted $10,000 to make the delivery. Around the same time, Krzyzewski called Brown's wife, Patti, to see how he was doing. She told him the story. The next day, a $10,000 check arrived. No note. Just the money.

"I knew some guys who were Carolina fans," Brown says. "When I gave them the stockings, I said, 'Oh yeah? What are the Heels doing for you?'"

When Krzyzewski decided to coach the U.S. national team, Gerry Brown, worried he'd be adding more to his full plate, jokingly asked her boss why he signed on for more responsibility.

"He's just as serious as you could be, very matter-of-fact, and he says to me, 'That's the only way I can serve my country,'" she says.

And in 2010, when Duke was playing in the Final Four in Indianapolis, Mlynski's 2-year-old grandson was at the Cleveland Clinic undergoing neurosurgery. Krzyzewski called his friend every single day to check in on the boy's progress.

"Amazingly, my grandson was released from the hospital on Sunday and we drove back to Indy, where my grandson and his family live," Mlynski says.

On Monday, there were tickets in Mlynski's name waiting at Lucas Oil Stadium for the national championship game.

IT IS EARLY December and Duke has just beaten Wisconsin, and, after the game, a few select people gather in the hallway outside of the visitors locker room.

Stepek is there and, of course, Mlynski.

He's always there if he can be. Best-friend status -- Krzyzewski was his best man -- has afforded the man everyone calls Moe a few perks. He's been in the bleachers when Krzyzewski recruited Chicago products Jon Scheyer, Jabari Parker and Jahlil Okafor.

He has spent the day in the Krzyzewski home on days of the Carolina game, and been in attendance for all of the Blue Devils' title victories.

So naturally, when the Devils play in Madison, Wisconsin -- a doable roughly 150-mile ride away -- he's there. After Duke won, a happy Krzyzewski is holding court, regaling folks with stories and tales until someone finally says the bus is waiting and it's time to go.

Krzyzewski goes from person to person, offering each a warm hug and sincere thanks, saving Mlynski for last.

"I say, 'You want me to kiss your ring?'" Mlynski says. "And he says, 'No. But you can kiss my ass.'"

You think you know Mike Krzyzewski?

Maybe you do.

But then again, you really don't.

Follow ESPN Reader on Twitter: @ESPN_Reader

Join the conversation about "Do you know Mike Krzyzewski?"