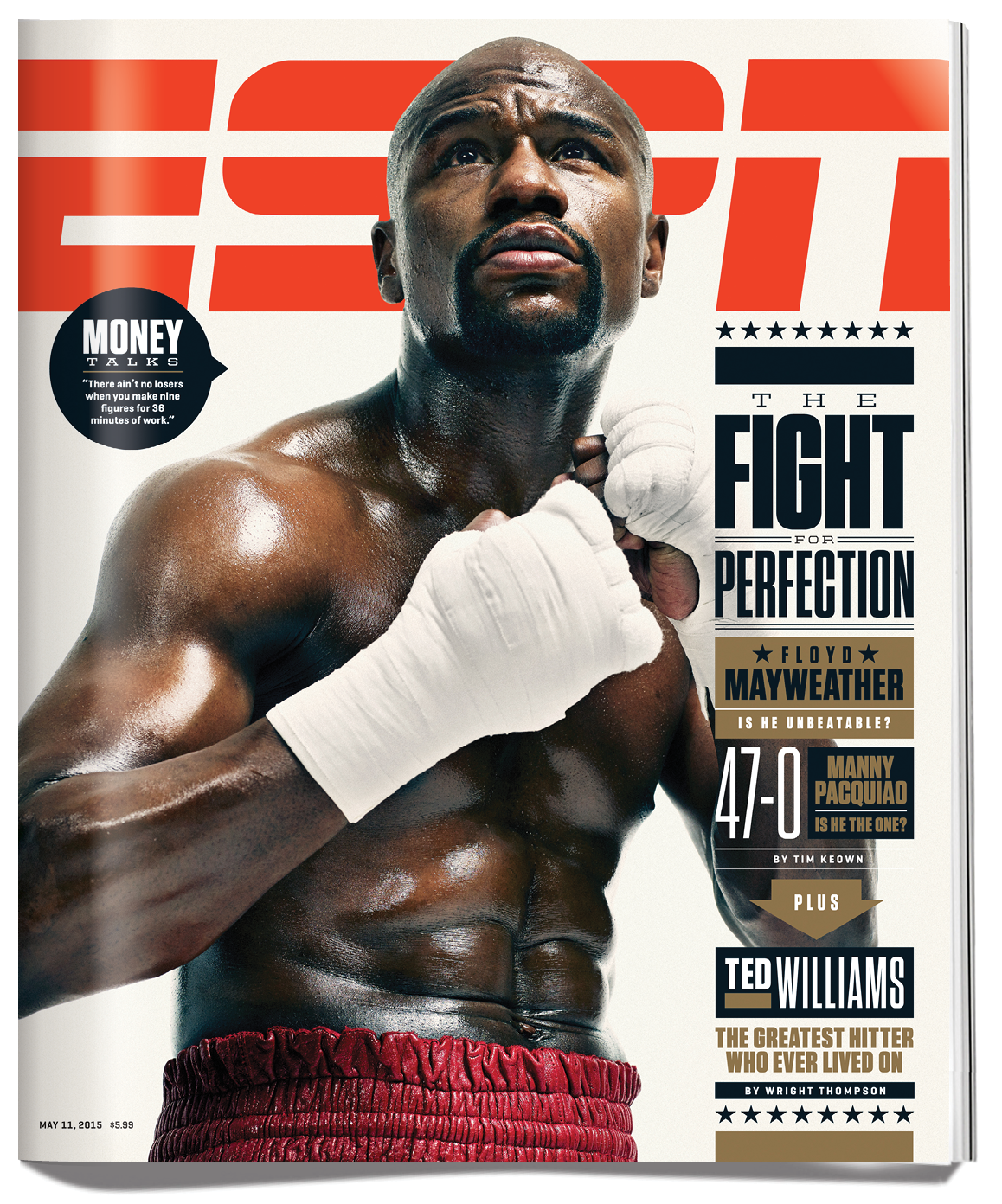

The Greatest Hitter Who Ever Lived On

Ted Williams' ambitions shaped his legacy but wrecked his relationships. If his lone surviving child has her wish, the family's cycle of suffering might at last be broken.

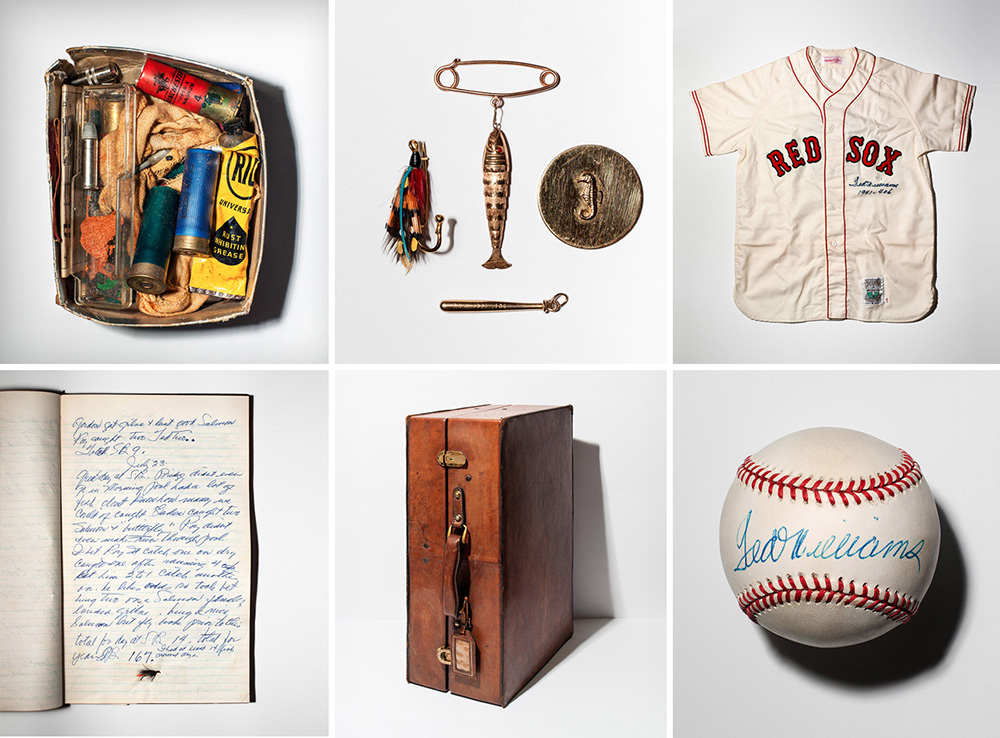

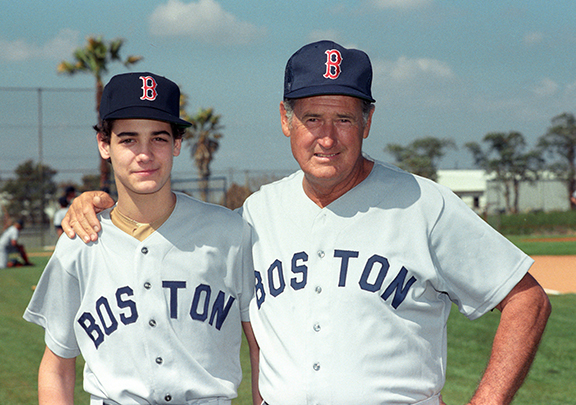

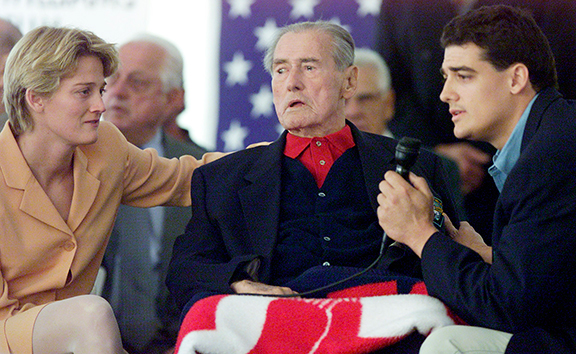

CLAUDIA WILLIAMS FOUND comfort wearing her dad's favorite red flannel shirt. It smelled like him. Time frayed the threads, pulled apart seams, and years ago the shirt went into a safe. She keeps many things locked away. In a closet next to her garage, her father's Orvis 8.3-foot, 7-weight graphite fly rod leans on a wall. His flies are safe too, and she can see his hands in the bend of the knots. She feels closest to him fishing but has been only once or twice since he died. Nearby, pocketknives rust at their hinges. His old leather suitcase is there too, in its final resting place after years of trains, ballparks and hotel rooms. Her husband, Eric Abel, comes home from running errands. He'd been through the safes and the storage unit they keep filled to its 10-foot ceiling, hunting for the flannel shirt. She is laughing in the kitchen, a lazy Sunday morning. Eric takes a breath and enters the room. "First of all, Claudia," he says slowly, "let me apologize; I don't know what we've done with that shirt." Suddenly quiet and hiding now, she says, "I don't wanna think about it," as one more piece of her father slips away. SHE IS HIDING from loss, and from regret, hiding from her family's past, which is always operating the strings of her daily life. Whenever she lets herself go back, she ends up at the same place: the beginning. Ted Williams' mother gave him nothing but a name, and as soon as he grew old enough, he gave it back, changing Teddy on his birth certificate to the more respectable Theodore. He longed to rewrite the facts of his life. His father drifted on the edge of it. His mother, May, was obsessed with her work at the Salvation Army, abandoning her own kids, and the descriptions of his lonely life exist in many accounts, most notably biographies by Ben Bradlee Jr. and Leigh Montville. San Diego neighbors would watch Ted and his younger brother Danny, 8 and 6, sitting alone on the front porch late into the night. The anger that dominated both their lives started there, on those lonely evenings outside 4121 Utah St., waiting for their mom to come home. May Williams never saw her son play a major league game, even though she lived through his entire career. When she died, 11 months after he hit a home run in his final at-bat, he went through her things and gathered up family photographs. He tore them into pieces and threw the pieces away. That was 1961, and he never wanted family to hurt him again. He lived most of the next 41 years as a kind of island. He died in 2002 and is frozen at 7895 East Acoma Drive in Scottsdale, Arizona. Claudia and her brother, John-Henry, supported cryonics; older half-sister Bobby-Jo wanted her father cremated and sued her siblings in the courts and fought them in the media. Ted Williams gave his three children the name he'd made famous, and when he died, their battle turned a solemn passing into a late-night punch line. Death exposes everyone, and it exposed Ted Williams, stripping away the armor he'd created as a boy on Utah Street, revealing what he'd tried so hard to hide: He came from damaged people, and he left damaged people behind. Reminders of her father are everywhere in Claudia's life. HENRY LEUTWYLER CLAUDIA WILLIAMS, NOW 43, rarely tells anyone about her relation to Ted Williams. Her co-workers at the Crystal River, Florida, medical center where she's a nurse are only now finding out on their own. It was two years before her best friend knew. If people do know, she tests them constantly, to make sure they don't like her for her dad's name. She recently stopped to pick up swim fins from a workout partner, and he said he was having an office party and invited her in. Instead, she sat in her car in the parking lot, stewing, wondering whether he just wanted to show off "Ted's daughter," and finally she drove away, enraged, leaving the fins behind. Upon occasion, she curses exactly like he did, stringing together blistering oaths, a kind of profane poetry: "that whore of a bitch f---ing c--- of a bimbo," say, of a nurse who spoke to reporters about the family. Claudia is beautiful and familiar, her face a combination of her mother's Vogue model cheekbones and her father's all-American jaw. When she is up, laughing with a goofy smile and light in her eyes, you cannot get close enough to her, and when she is down, spiraling into a darkness only she can see, you cannot get far enough away. With no children of her own, she's destined to remain a daughter. She's young because her dad was much older than her mom -- Ted, the eternal player, tossed Dolores Wettach a note across the first-class cabin of an international flight, introducing himself simply as a fisherman -- starting Claudia's lifelong struggle to hold tight to something slipping between her fingers. "I hate time," she says. She lives in a sprawling Florida community popular among retirees whose first resident and primary pitchman was her father. He's everywhere. Her country club membership number is 9. Every day, she drives on Ted Williams Memorial Parkway. She turns from West Fenway Drive onto Ted Williams Court in her blackAcura, the Euro club music rattling the rearview mirror. "You should look at the lyrics," she says as the stereo plays. The songs bleed together into a singular anthem of loneliness and loss. This will be my monument / This will be a beacon when I'm gone / You're everywhere I go / I promise I won't let you down / It's not over, not over / Not over, not over, yet. The lines speak to the two competing desires governing her life: She wants to be close to a father she didn't really know for much of his life, but she wants to escape his shadow too. She left home at 16, moving to Europe to finish high school, working as a nanny, training for triathlons, living in France, then Switzerland, then Germany, any place where nobody'd ever heard of Ted Williams. In letters home, she described being adrift, telling her dad she felt "like a lost athlete looking for a sport." She cooked hot dogs in a gypsy circus. Her father offered her money, but she refused it. In this stubbornness, she found the emotional stability sought but never discovered by her brother, who died 11 years ago from leukemia. "I surpassed John-Henry quicker because I got away," she says. She never asked for anything. Her dream was to attend Middlebury College in Vermont. When she didn't get in, Ted called the governor of New Hampshire, who pulled some strings. The reconsidered acceptance letter made her weep with rage because she knew what had happened. She told Middlebury no. Her friends at Springfield College didn't realize her father was Ted Williams until she asked some guys who played baseball to teach her to throw; the Red Sox had requested she toss out a first pitch as a surprise to her father, and she didn't want, as she told them, "to throw like a girl." Her brother lobbed one wild, but Claudia kicked her leg and delivered a strike. Ted beamed, a reward she seldom got while he lived and craves now that he's gone. "I think I'm just looking for him to still be proud of me," she says. She trained for a triathlon and then devoted her life to making the 2000 Olympic team, falling just short. Around 2005, she started playing tennis with some older ladies in the neighborhood. Then the Williams kicked in: She moved up the USTA ratings, 3.5 to 4.0, then, she says, she became the best 4.0 in Citrus County, then the top-ranked 4.0 player in the state. Hooked, she decided to play at the local junior college. For a season, at 37 years old, she competed against teenagers. After her father died, she received a sponsor's exemption to run the Boston Marathon in his memory; she turned it down, trained and ran fast enough to qualify on her own. "I don't know who has to say, 'You did well,'" says Abel, who was the Williams family attorney when he met Claudia. When she decided to be a lifeguard, she completed the most advanced open-water rescue training. After deciding to make jewelry, she took classes to become a master craftsman. She learned how to sky-dive, and after having to deploy the backup chute on her first solo jump, she went back up again: I'll show you, sky! Her workout routines -- miles in a pool and on a treadmill, hours daily in a gym -- break the alpha dogs who try to hang with Ted's daughter. She makes them earn their story. In the past few years, she studied nursing, and even that hasn't been enough, so now she's studying biology and statistics, prerequisites for graduate school. Her top choice is Duke, and in her application essay she talked about her life as a frustrated athlete without a sport. She talked about the influence of her father, but she never mentioned that the father in question was Ted Williams. Williams hits one of his career 521 home runs, shown here in the late '50s. TONY TOMSIC/WIREIMAGE/GETTY IMAGE THIS STORY BEGAN two years ago, when I reached out to Claudia about meeting at her home in Hernando. The timing never worked for her because she struggles to look past her obsessions: nursing school and a book she wrote about her father, which started as a stocking stuffer about lessons she learned and turned into a cathartic exploration of the person she's still trying to be. Finally she said yes. The first visit lasted a week in the fall of 2014, and we made paella and she told funny stories about her dad -- he'd call the public phone in European hostels and boom at unsuspecting travelers, "Is CLAUDIA WILLIAMS there? This is her FATHER! OL' TED WILLIAMS!" -- and she got melancholy later and said, "We need to laugh more." “I think I'm just looking for him to still be proud of me.” - Claudia Williams She let me poke through the family's filing cabinets, its safes, her dad's hospital records, anything I wanted -- she could prove, she said, that her father agreed to be frozen. We talked for hour upon hour. To her, the many accounts of Ted Williams are all fatally flawed because most people didn't understand that the two famous acts of his life -- ballplayer and fisherman -- occurred only because he was hiding from the third and final act of his life: fatherhood. He'd been raised by an erratic and absent mother. He had a cousin who was murdered by her husband, and a criminal brother who died young and angry. He hid in the hyperfocus required by baseball and fishing; most nights after ballgames, he returned to the hotel where he lived -- he never purchased a home in Boston -- and tied fishing flies alone. He preferred to spend offseasons in the woods or on the water. Once, he arrived late to spring training because he lost track of time while hunting wolves in a cold northern forest, and the media focused so much on the process story of the tardiness that nobody seemed to notice the window Williams had briefly opened into his truest self: He sought peace in the wilderness with wolves. TED WILLIAMS HATED his childhood home, leaving before graduation the same as Claudia, never going back. His lifelong feud with the press began when a writer asked rhetorically in a column what kind of boy didn't go home in the winter to visit his mother. How could he be expected, then, to create a family when he despised his own so much? "I was for s--- as a father," he confided once to a cousin. On the day his only son, John-Henry, was born, Ted was salmon fishing in Canada. He'd been retired for eight years. That night, like always, he wrote in his fishing log. Ted wrote about the water temperature (70-72 degrees), his friends who came up to fish, and details of the trout and arctic char he caught while casting for salmon. He never mentioned a pregnant Dolores, and he never mentioned the boy. To the public, he was a success, but to himself, he was a failure, consumed with shame and regret. Bobby-Jo came into the world first, in the middle of his career. When she was young, he got so mad at her that he spit a mouthful of food in her face. Ted drove her back to her mom's house in Miami once, and when they arrived, it transpired that Bobby-Jo had forgotten her keys, and Ted, raging, kicked her out of the car and left her standing alone there in the dark, exactly as his mother had done to him. Instead of Bobby-Jo becoming the first Williams to graduate from college, which Ted wanted as desperately as he wanted to hit a baseball, she got pregnant. Rather than tell her father, she slit her arm from the wrist to the elbow. She entered a psych ward, which he paid for, and got an abortion, which he paid for, and when her scars taunted him -- physical proof that he'd become his mother -- he paid for plastic surgery too. He couldn't buy her peace. Doctors diagnosed manic depression, and she moved from booze to pills, cheating on her husband with the neighbor and giving herself another abortion with drugs and alcohol. Doctors gave her electroshock therapy. She threw plates and knives. Her voice turned childlike whenever she spoke to him, a thin "Daddy." She asked for money and begged for help. She never held a job. At the funeral for Williams' longtime girlfriend, Louise Kaufman, Claudia recognized her half-sister, Bobby-Jo, whom she'd never met, simply by seeing a familiar wave of fear register on Bobby-Jo's face at the sound of Ted's voice: He boomed in the next room, sucking up all the oxygen, and two women, born 23 years apart, flinched. "You must be Bobby-Jo," Claudia said. "Claudia?" she replied. Ted talked with Bobby-Jo moments later. "Hi, Daddy," she said. "Are you still smoking?" he asked. "I'm down to one pack a day," she said. "Jesus," he said, then he walked away. By the time Eric Abel came into the Williams inner circle as the family attorney, Ted had already excommunicated Bobby-Jo. At Ted's request, Abel wrote her out of the will, and Abel said over the nine years he spent around Williams, he heard him mention Bobby-Jo maybe three times, and every time he called her a "f---ing syphilitic c---." He called Claudia a "c---" too, and a "fat bitch," and told John-Henry he was the "abortion I wanted." They tried to understand his rages, and why they'd even been born. "I mean, he had [me] at 53 years old," Claudia says, her voice wavering. "Right from the start, we knew we weren't gonna have much time, you know? The lessons that he had to teach us, we didn't have the time to learn. ... We're desperately trying -- I say 'we' like John-Henry's still around -- but we're desperately trying to figure out what made him tick." Their mom, Dolores, and Ted didn't last long. He got his freedom, fishing every day. She got the kids. Claudia remembers growing up with a mother increasingly bitter over her failed love affair, on a Vermont farm without a television, isolated by their environment and the fame of their absent father. The children created their own world, and only they understand what it felt like to live in it. All they had was each other, and both longed to decode their dad, and maybe find themselves in the process. Whenever they'd ask questions about his childhood, or his life, he'd scowl and grumble, "Read my book." Just a part of the collection of artifacts fills a storage room to its 10-foot ceiling. Henry Leutwyler for ESPN Magazine CLAUDIA LOVES DRAGONS. She especially loves movies about dragons. On the living room cabinet, there's a ceramic statue of Toothless, the star of the animated movie How to Train Your Dragon. She got it as a gift. Her voice changes and her eyes and face soften when she says "Toothless." A few years ago, she and Eric's teenage daughters from his first marriage went to see a movie called The Water Horse, about a boy who raises a Loch Ness Monster -- which is close enough to a dragon for Claudia -- then releases the beast to save its life. It is named Crusoe, and as the movie ended, Eric's girls looked over and saw Claudia weeping, shoulders rocking up and down, distraught over the boy taking the dragon out to sea. "You were sobbing," says Eric's daughter Emma, now 22, grinning as she tells the story. Claudia smiles. "My heart hurt," she says. That night, after Eric cooks steaks and Emma bakes sugar cookies, everyone piles onto the sofa for movie night. Claudia picks How to Train Your Dragon, bringing another round of catcalls and laughter. Everyone settles in, and the movie starts. "Toothless!" she coos. "He's real to you, isn't he?" Eric asks, kindly. No one is laughing now, and Claudia reaches for Eric's hand from time to time. Every now and again, she sighs. The story is about a boy trying to live in the shadow of his powerful and domineering father -- about a child searching for his place in the world. Watching her watch a dragon movie makes it all make sense. Sitting on her couch, she cries when the dragon saves the little boy. "You won't always be there to protect him," a character in the movie tells the father, and Claudia smiles, turns to Eric and says, "John-Henry would've loved this movie." JOHN-HENRY WILLIAMS loved frogs. He loved anything small and weak. During storms, driving up the hill toward their house in Vermont, he'd jump out of the car in the pouring rain, trying to get the frogs to move before they died beneath the wheels of the car. Like any damaged person, he took his protection too far. He saved a wild duck he found, and countless other birds. If they bit him, he'd tap their beaks to scold them, as if they loved him with the same intellectual fervor he loved them. Claudia still remembers Bangor the Cat. Driving back from visiting Ted's compound in Canada, Dolores and John-Henry stopped in Maine to spend the night in sleeping bags at a rest stop. In the night, he heard a kitten crying, and after searching for and finding her, he tucked the cat, fleas and all, into his bag. At home, he brought her back to health and felt hurt when she wanted to roam outside. Always scared of being abandoned, he fit a dog harness on a long leash and tied Bangor to his bed. Claudia tried to get him to release the cat, but he refused to listen. He protected Claudia too. The first time they visited Ted in Florida together, he made sure she knew not to annoy him, advising her to use the bathroom before leaving the airport. At Ted's place in Islamorada, in the Keys, she got a terrible sunburn. Terrified of Ted raging at them, John-Henry quietly fed her ice chips and got her ginger ale when she vomited from sun poisoning. She was about 9. He was 12. John-Henry rubbed Vaseline on her shoulders and told her not to cry. A young John-Henry poses with his father during Red Sox spring training. CLIFF WELCH/ICON SPORTSWIRE/AP IMAGES That was three decades ago. There is only one picture of John-Henry in her house. It hurts too much. When he got leukemia a year after Ted died, she donated bone marrow, and when he needed another transplant and her blood count was too low, she begged the doctors to try anyway. She screamed at them in the blood lab. An agnostic, she stopped in a church near the Los Angeles hospital and got on her knees and begged. It was the first and only time she has prayed. She asked God to take her instead. John-Henry died on a Saturday, and as he requested, his body was suspended at Alcor too, in the same tank as his dad. Eleven years he's been gone. "Grief is weird," Claudia says, riding at night through the dark neighborhoods around their house. "The first seven years, any time I would have a break, any fun, one moment -- inevitably, guilt. Just horrible guilt. Like I didn't deserve to be happy." "I'm the one who reached down to keep pulling you up," Abel says, driving. "Still do. I love you. When you laugh -- " She interrupts him. A heavy rain is falling, blurring the streetlights reflecting off the asphalt, and she looks out into the glare of the headlamps and sees something move. "Did you see the frog?" she says suddenly. "You gotta watch for him!" "No," he says. "I don't know if you ran over him," she says. "Did I hit one?" he asks. She starts slapping his arm. "Stop! Stop!" she cries. He presses hard on the brakes, and she gets out. In the rain, in the glow of their house, she shakes her foot along the pavement, clearing a path, making sure no frogs get caught beneath the tires of the approaching car. Williams constantly looked to the wilderness for peace. AP IMAGES A MILE AWAY, a secret remains locked in one of Ted Williams' safes. On a shelf above a Desert Eagle .44, his fishing logs tell a different story from the one he gave his fans and his children. In public, he seemed to revel in the solitary pursuit of baseball greatness, then fishing greatness, but really, his lonely existence was a self-imposed exile, not because he didn't want to know his children but because he was scared of hurting them, and of being hurt. Something happened to Ted Williams in the years after his son came into the world. "What's incredible as an observer was to watch him in love with his kids," says Abel, now 52. "The vulnerability of having love for your children. You could see it just gnaw. It was everything against his grain to succumb to this outside influence of children. Love had control over him. He felt vulnerable. A vulnerability he never had in his life. I think he hated that vulnerability of feeling guilt." In his logs, John-Henry and Claudia began to make appearances. First, just simple mentions, when they were little: "Claudia, John Henry took canoe ride to Gray Rapids." Soon Ted gave them praise that would never reach their ears. By 1979, when they were 10 and 7, he practically gushed in his upright, loopy handwriting. On June 14, he wrote about his son: "His casting is better than I expected so he must have been practicing some. After an aching rest and a few blisters on his casting hand, he is getting a little uninterested. Finally he got his first fish. A grilse. Enthusiasm revived. 3 grilse, caught his first salmon. 10 pounds. Big day in a young fisherman's life." Claudia and John-Henry would have given anything to know this. It might have changed their lives. Near the safe in his old house is a note Ted saved, dated Dec. 10, 1983, when Claudia was 12. It's a contract she wrote -- the Williams family loves handwritten contracts -- with her mother at a Howard Johnson's somewhere: "When I grow up I will never have a child. If I do I will pay my mom 1,000 dollars." “Love had control over him. He felt a vulnerability he never had in his life.” - Claudia Williams Less than a year later, Ted sat before a stack of posters, doing one of the bulk signings familiar to all famous athletes. At some point during the session, instead of signing his name, he wrote a note to Claudia, one he knew she'd discover someday. He signed the rest, and the whole box went into storage. She found the note three years ago, 10 years after he died, going through memorabilia. Trembling as she held the poster in her hand, she finally read the words she wanted so badly to hear as a child: "To my beautiful daughter. I love you. Dad." TED WANTED TO change. Trouble is, nobody knew how to start to repair something so completely broken. It began with Claudia. About 20 years ago, she graduated from college. He asked her what she wanted as a gift, and she said she wanted time. The three of them flew together to San Diego and drove up the Pacific Coast. It was a do-over. So many firsts happened on that trip. She and her brother saw the house on Utah Street. The three of them laughed, and they asked Ted questions, and he told stories and asked them questions too. For years, she'd thought her father had stopped maturing when he became famous at 20, and now they'd both reached his emotional age, equals and running buddies for the first time. He never lost his temper or spun off in a rage. He wasn't angry, and they weren't scared. They visited Alcatraz, and Ted used a Walkman for the first time, befuddled by the technology, and they all laughed. Something happened to Ted Williams' face when he laughed; most pictures show him stern, in concentration, but when he giggled, his jowls would hang and his eyes would squint and he looked, for just a moment, nothing like one of the most famous men in America. He looked anonymous and happy. When the boat docked back at Pier 39, they walked down the boards looking for dinner. A man at a card table was reading palms. Claudia saw him first, and she and John-Henry dragged their father over. The fortune-teller sat on a low stool. He traced his finger over the old man's wrinkled palm. Ted laughed and made a joke about it feeling good, and the inside of his hand was soft, the calluses he cultivated during baseball long gone smooth. John-Henry snapped photos, forever documenting every moment he spent around his dad. Claudia leaned in and watched. Everything that would happen began in these moments, but none of them could see the future, not even the fortune-teller. He looked up at the old man. "You have heavy burdens you're still carrying," he said. "It's time to let them go." Ted Williams tried to follow that advice. He really tried. John-Henry looks over a special edition of Boston Red Sox Monopoly with his father in 2000, two years before Ted's death. CBK GROUP/AP IMAGES NINE MONTHS AFTER that trip, he had a stroke. His health declined steadily for nearly the next nine years. John-Henry and Claudia cared for him every day, and every day they discovered new levels of understanding and knowledge. They sought out anything that might buy him more time -- no matter how experimental, unorthodox or just plain weird. They paid $30 a pill for vitamins and pumped oxygen-rich air into his room. They tried bee pollen and acupuncture and hired a therapist to work through his anger. John-Henry bought a dialysis machine so Ted could get the treatment at night. Nothing worked. Father and son had epic fights, bad enough that the caretakers called protective services. Investigators came to the house and interviewed both men, asking whether Ted was being made to sign autographs against his will, before determining there was no abuse. John-Henry wanted to control his father -- his latest Bangor -- and his father rebelled. About once a year, Abel would get called to the house to mediate a bizarre dispute, usually about Ted showering to ward off infection, or taking his medicine regularly. "You could see an internal struggle," Abel says. "'Goddamn, that's my son. He loves me, I love him. F---. I wanna say no so goddamn bad. Everything about me says no. But I love him.' You could just watch it rage." Even now, Abel laughs about the scene he'd find upon entering the house. "Dad, you have to take this medicine," John-Henry would be saying. "You have to take these pills." "I'm not taking this s---," Ted would growl, seething. "F--- you." Abel would write up a contract on a napkin or a piece of scratch paper, which is what Ted liked, and negotiate a settlement: Ted agreed to take the pills every day, and John-Henry agreed to let him shower only four times a week. Both would sign it, and the crisis would be averted. Even as he fought him, Ted knew John-Henry was struggling to find his place in the world. He worried about his son. Once, when Abel was flying to San Diego to meet with the Upper Deck baseball card company, Ted pulled him aside. "See if you can help John-Henry get a job," Williams asked. "I know Claudia will be fine." The guilt Ted carried slipped away when he did something to help his kids. Looking back, Claudia wishes she'd let him get her into Middlebury, because it was the only thing he knew how to do. In those last years, she taught him how to be a father to a daughter. When Claudia went through a breakup, instead of keeping her pain a secret like she'd done as a teenager, she explained how to comfort her. "Please don't be mad," she said. "Just please listen to me. I'm hurting." She could hear him grinding his teeth. "What the hell do you want me to do about it!" he yelled. "I can't do a f---ing thing!" "Just tell me you love me," she said. "JESUS CHRIST!" he yelled. "I love you more than you'll ever know." The outside world slipped away, and the universe shrank to the three of them: a dad looking for absolution, a son who needed a dad to show him how to be a man, a daughter who'd always craved a family, which they at long last became. A strange family, to be sure, but a family nonetheless, with a patriarch who'd found escape from his guilt and his shame in the company of his children. "He never thought he was gonna be a good father," Claudia says. "He'd given up on it. Thought he wasn't very good at it. And we actually showed him that not only was he good at it, we wanted him and we said, 'You can do this, Dad.' And once he realized 'I can be good at this, and these kids want to learn from me,' we had run out of time." Then John-Henry read a book about cryonics. EDDIE GUY TED'S HOUSE IS full of secrets about his son too, windows into a desperate but curious mind at work. In the long row of filing cabinets, a drawer holds a blue folder marked "Alcor." It's thick, jammed with newsletters, receipts, contracts and John-Henry's handwritten notes taken during a visit to the cryonics facility. He filled six yellow legal-sized pages, jotting down the price for freezing just the head ($50,000) and the price for the entire body ($120,000), making charts and decision trees plotting the potential repercussions of cryonics. On a page, he drew a horizontal graph, with a line drawn down the middle, dividing the plan into actions he'd take before convincing his father and what he'd need to do after. In big letters, he wrote "Make Claudia co-petitioner" and circled it. She agreed. "I didn't want John-Henry to lose his father," she says. "He needed him so badly. He was still learning, he was still -- he was still -- what is it? Evolving? Becoming a man in his father's eyes? He needed more time." The literature John-Henry took home from Alcor, one of the country's two major cryonics companies, worked in his imagination; he purchased every book they offered, according to credit card receipts. The most important thing he read was the origin text of cryonics, a book by science fiction writer and professor Robert Ettinger titled The Prospect of Immortality. Ettinger wrote that the freezer always trumped the grave, and with nothing to lose, why not take a chance? Children who buried their parents were described as murderers. Ettinger also made many other wild and foolish predictions about what science would bring to the world in his lifetime, so the book, like the Bible, is believable to those who want to believe. On page 5, Ettinger seemed to be speaking directly to John-Henry: "The tired old man, then, will close his eyes, and he can think of his impending temporary death as another period under anaesthesia at the hospital. Centuries may pass but to him there will be only a moment of sleep without dreams." Around the long kitchen table, John-Henry began to make his case. Ted did not want to be frozen at first. His will, which he wrote near the end of the fishing act of his life, made his wishes very clear. He should be cremated, his ashes "sprinkled at sea off the coast of Florida where the water is very deep." Four years passed between John-Henry's purchasing the books and requesting membership documents from Alcor. Ted's health declined, more every day. John-Henry kept saying cryonics provided a chance for them all to be together again one day. "What does Dad think?" Claudia asked. “Once he realized 'I can be good at this, and these kids want to learn from me,' we had run out of time.” - Eric Abel "He thinks it's kooky," John-Henry says. "But he is interested. I can tell." They spent hours around the dining table, and every so often John-Henry would bring it up. Sometimes Ted would curse and walk away. Other times he'd listen. These private discussions would eventually become public, fitting into an existing narrative. John-Henry Williams, a 6-foot-5 ringer for his handsome father, had long lived in the zeitgeist as a bumbling son who took and took without ever standing on his own. In the definitive biography of Ted Williams, by Ben Bradlee Jr., John-Henry is shown as a terrible businessman and a cheat, someone who lied so often -- inviting his dad to a college graduation where he didn't actually graduate, claiming to make his college baseball team when he never tried out -- that he lied about Ted's wanting to be frozen too. This depiction of her brother by an author she cooperated with haunts Claudia, who believes her dad knew better, and she feels like the only one left to defend John-Henry. After Ted died, friends told reporters that Williams disagreed with his son's obsession. The stories and biographies quote staff members and associates who say Ted continued to want his remains scattered in the Atlantic, and in the end, Bradlee seemed to conclude that Ted did not want to be frozen. Abel goes into the study and comes back with the book. He opens it on the kitchen counter, the pages full of his notes, some passages marked with a check if he feels they're accurate, other quotes highlighted and some with sharp, angry pen strokes when he's aggrieved, the margins littered with "not true" and "bulls---" and "lie." Bradlee spent a decade reporting, and while Claudia and Eric say he got many things about Ted's military and baseball careers right, they say he allowed unreliable people to give opinions couched as facts when discussing the inner workings of the Williams clan, which has forever been a complicated tribe in which truths are perceptions and history keeps repeating itself: Bobby-Jo died five years ago, of advanced liver disease, killed by the same bad habits as her mother. Just months before his death, Williams makes an unannounced appearance at the Ted Williams Museum and Hitters Hall of Fame. COLIN BRALEY/REUTERS/LANDOV The clean cryonics narrative of Bradlee's book doesn't match the messiness of that long family dispute. Claudia has spent considerable time looking for documents that would prove she was in the hospital for the signing of the informal contract. Bradlee's book strongly suggests, without ever saying so directly, that she was lying about being there. She says she visited the hospital so many times that all those trips ran together, but she remains steadfast: Ted signed a piece of paper. The argument remains frustrating for everyone: Claudia can't prove they followed her father's wishes, and Bradlee can't prove they didn't. Nobody quoted is without an agenda, whether fueled by anger, misunderstanding, jealousy or love. Nobody is unaffected. Nobody is clean. It's a mess, all of it. Ted Williams left behind so many unanswered questions that two of his children went to the extreme edges of science to find more time for them to be answered, while his third child went to equal extremes to stop them. At the end, jealous and estranged, Bobby-Jo raged, leaving bizarre voice mails on Abel's answering machine: "This is Barbara Joyce Ferrell. I live right behind you. Prepare thyself, sir." Bobby-Jo lashed out, and Claudia hid, and John-Henry got as close as he could. He pushed and explained his idea, working cryonics into those dinner-table evenings. One night, Ted looked at Claudia and asked, "Are you in on this too?" "Who knows what the future will bring?" she said, and John-Henry argued some more. Ted, exhausted and struggling to keep his eyes open, sort of laughed, then his son helped him to the recliner where he slept. Months passed, and after trying every other option available to buy time, only surgery would help Ted. First, he needed a heart catheterization, and doctors worried he might not survive even that preliminary procedure. Most people his age wouldn't risk a series of operations. In her book, Claudia writes what her father told the doctor. "Doc, if you can give me any extra time with these guys, let's do it," he said. "I've had a great life, and what the hell, if I die, maybe I'll die on the table. I'd like to have some more time with my two kids." The doctor nodded and scheduled the surgery. Claudia began to cry, and Ted's voice cracked when he tried to comfort her, as she'd taught him to do. "It'll be all right," he said. According to Claudia, that's when John-Henry returned to the Williams family favorite: the nonbinding, casually written contract. She says Ted sighed, agreed to go along with their wishes and signed a piece of paper agreeing to be frozen. He knew he might not live through his procedure, and at the end of his life, he'd finally put aside his own wishes for theirs. For comedians and baseball fans and biographers, cryonics was a joke or a disgrace, but inside the Williams family, it was a profound act of love, a conscious attempt to undo the cycle of pain both felt and caused. "If it means that much to you kids," he said, "fine." SHE AND ERIC fell in love during the horrible siege after they froze her father, who died of cardiac arrest almost two years after signing the note. She was trapped in his house by television trucks and reporters shouting questions. Claudia, then 30 and an elite athlete, paced the halls like a wild animal. Days passed without her manic exercise routine, which she used to exhaust herself into a kind of peace. Finally Eric realized she needed to escape, so he put her in the back seat of his car, covered her with blankets and snuck her past the cameras. They drove to a nearby park, where she could run until she felt tired enough to stop thinking. That was 13 years ago, and while people still remember something about Ted's head being frozen, the daily onslaught is over. Claudia and Eric are moving back into Ted's old house, not wanting to sell it and not wealthy enough to maintain two homes. It's empty now, under renovation, sitting low and wide on a hill, beneath the grove of live oak trees. Claudia and Eric pull into the drive, the gate with the red No. 9 closing behind them. Her mood founders when she stands in the towering great room, cold and unfurnished now, except for row upon row of almost empty bookshelves rising toward the ceiling. The only thing left is a frayed set of Ted's beloved Encyclopedia Britannica, which he bought after retiring, spending hours scouring them for the knowledge he felt ashamed not to have. When he was an old man, Harvard begged him to come and receive an honorary degree. He refused, over and over again, never feeling as if he belonged in a place with such educated people. "I don't think [Ted] at the end of his life felt like he accomplished anything," Abel says. "Ted had that constant insecurity." “I don't think [Ted] at the end of his life felt - Eric Abel The house is empty inside, dangling wires and pencil marks on the walls indicating where a range will go. Ted's white Sub-Zero fridge with the wood-paneled front is unplugged in the corner. The kitchen brings back so many memories. The wires and the hoses and the sawdust on the floor amplify how much those memories have faded. The dining table used to be there, by the window. Training for triathlons after she came home from Europe, every weekend Claudia would ride her bike here from Tampa. "Daddy would sit right here," she says, laughing. "He would see me coming up the road. He'd be waiting for me right here. When I walked into the house, there'd be a hot dog on the table." She didn't like hot dogs, but she loved to see her father smile, so she ate them every time. "He thought I needed salt," she says, then switches to her flawless Ted Williams impersonation, a chin-jutting bass drum: "Yup, isn't that GOOD? That's a good hot dog, isn't it? OL' TED WILLIAMS, HUH? YOU WANNA 'NOTHER ONE?" Her spirit lightens when she does his voice, everything lit from the inside. They spent hours at that table, talking, playing the games he never got to play as a kid -- As I was going to St. Ives, I met a man with seven wives -- and debating religion and the nature of life and death. "Those late nights when it was clear he didn't have much time left ...," she says, trailing off, the light gone. In public, Williams seemed to revel in the solitary pursuit of baseball greatness, then fishing greatness, but really, his lonely existence was self-imposed. MARVIN KONER/GLOBE PHOTOS/ZUMA PRESS SHE HAS LOST her father to old age and her brother to leukemia. Every year, she plants a tree in their memory, and leaving her dad's house one day, she sees that one of John-Henry's trees is dying. Reminders of grief surround her, and now her mother is fading too. One afternoon, she gets a frantic phone call and rushes to her mom's bedside less than a mile away. The live-in caretaker is crying. Claudia, a nurse, listens to the plodding thumps of a tired heart. She checks her mom's blood pressure: 86/60 and dropping. "Mom, you want to go to the hospital?" Claudia asks. "No," Dolores Williams says. "Even if it means saving your life?" "No." Her mom stabilizes, and Claudia heads home. The rain pounds the roof of her car. Soon she will face herself alone, as her father faced the world stripped of the soothing focus of baseball and fishing. Tears roll down her cheeks. She sighs hard; rattling almost, jagged on the edges, a noise so full of pain that people who hear it feel compelled to protect her. "Our time is running out," she says. She feels lonely. She's a young woman living among retirees with only a few friends. Everyone she has ever loved except for Eric is gone or almost gone, and she's sure she'll outlive Eric. "Who's gonna take care of me?" she sobs. There is a possibility. Before John-Henry died, he froze some of his sperm, and as executor, she controls it. As she parks her car and goes into the house, she's deciding whether to share an idea that has been gaining momentum and fervor. "The legacy deserves to go on," she says finally, crying harder than before. John-Henry had asked her to keep the family alive. "You have to have a child," he told her. The idea is strange, yet mechanically quite simple: She'd need a surrogate mother and a name. Back at home, all of it piles up, hurt stacked upon hurt, so what started as sadness about her mom became fear and desperation over the family coming to an end with her, and she's just dissolving in her high-ceilinged kitchen, coming apart. This is the vision greeting Eric when he walks in from work: his wife, her face red and puffy, sobbing so hard she's struggling to breathe. When she sees him, she stretches out her arms. Eric rushes toward her. "Mom's having a bad day," she tells him. "She's tired. It makes me angry, of course. She's the only thing I have left." She asks him again about creating and raising Ted Williams' grandchild. "That's still something, right, on the table that you and I might do?" she asks, hopeful. "We might do that?" Normally he's not keen on the idea. "Yes," he says. "We might?" she says, sounding vulnerable and shaky, like she's grasping for something beyond not only her reach but even her ability to name it. She's searching, searching for a father, for a purpose, for a child, searching for the chance to complete what her dad started in the last decade of his life. That's the hope and the promise of whatever life remains in John-Henry's sperm. Doctors told her there's enough genetic material for one chance at insemination, and as long as it remains frozen, some part of her brother, and her father, remains alive with it. She also has considered using her egg and Abel's sperm to create a child, going back and forth between the ideas. She's searching for a way to break the Williams cycle -- either by letting it die with her or by being the first good parent in generations -- and she's searching for something much more elusive too. She never saw her father's body, and nothing forced her to really accept his disappearance from her life. Every culture has deeply symbolic rituals for burying and mourning the dead. With Ted's remains in stasis -- they didn't hold a memorial service, not even a small, private one -- she hasn't moved past grief into acceptance and peace. With time, she's come to regret not having a funeral. She's searching for how to say goodbye, or maybe a way to move on, which often feels like the same thing. Today Claudia and husband Eric are looking at options to carry on her father's legacy. HENRY LEUTWYLER BEFORE CLAUDIA DROVE me back to the airport, Abel quietly asked me to keep in touch because she didn't meet many new people and really struggled with goodbyes. I left wondering what kind of life awaited her. Maybe she'd just find ways to exhaust herself, and find obsessions to occupy her mind, day after day, year after year, never breaking free of her father and never feeling as if she had honored his memory either. But something happened in the months after our first visit. It started with her book, Ted Williams: My Father. She stepped out of the shadows and did readings. The Red Sox hosted her in Boston, and a big crowd showed up, and people cried when she shared her memories, her joys and her pain. One at a time, they said she'd shown them a side of Ted Williams they'd never known. She did an interview in the Fenway stands, sitting in the red seat marking the longest home run ever hit in the ballpark, off the bat of her dad. She got lost in thought, staring down at the tiny home plate, feeling a strange connection. She walked past the hotel where he lived, long ago turned to luxury condos. His presence seemed real. The people most affected by her book were the fans who idolized her dad, now going through the same struggles of aging and illness he had. She got a letter from Jimmie Foxx's daughter. "You are our voice," it said. Seeing the joy she brought to the elderly, long her favorite group of people, reminded her of an old man she treated as a student nurse. He was difficult, so she tried talking to him about baseball. "I love the Red Sox," he said. "Me too," she replied. "I was there at Fenway Park when Ted Williams hit his last home run," he said. "It was a bright, sunny day, and I was there." "I was told it was a cold and overcast day," she said, then did something she never does. She told him she was Ted Williams' daughter. He beamed, and the next day, everything about him seemed different, and not just because he wore Red Sox gear head to toe. He smiled, and seemed lighter. It's the same look her father got when she'd care for him in the last years of his life. Those memories, and the reaction of the elderly readers, finally pointed her toward her long-sought purpose. As part of her application and interview process at Duke -- still a long shot, but her dad taught her to try to be the greatest -- she said she wanted to specialize in gerontology. "It wasn't until I cared for my elderly father as his health declined," she wrote on her application, "that I discovered my true calling." Now she just needed to get into a graduate program, do years of studying and open her own nurse practitioner's office. Every patient who walked through the door would get treated like Ted Williams. She didn't want to waste another moment. She felt time rushing away. The last two weeks before finding out, she swam miles in the pool and pounded out sets in the gym. Finally an email from Duke arrived asking her to log on to its website for the school's decision. She opened the link and started to read the letter. "Congratulations," it began. CLAUDIA GRINNED WHEN I walked back into her house the day after she was accepted to Duke. Standing around the kitchen, she and Eric told the story of what happened when she opened her letter. Eric rushed home and found her sitting at the computer, quiet and solemn, validated for perhaps the first time in her life. Soon she'll be studying online for a master's degree from one of the greatest universities in the world. Even in her moment of triumph, something worried her, a neurotic fear. "Do you think they accepted me because of Dad?" she asked, "or do you think they accepted me because of me?" Everyone who knew Ted Williams knows that his daughter's going to Duke would mean more to him than his home runs and war medals combined. "Daddy would be so proud," she said. "I think he knows," Eric replied. The house felt different than before, desolation replaced by hope. A Louisville Slugger leaned in the same cabinet as Toothless the Dragon, the first bit of baseball memorabilia in the living room. The renovations on Ted's house are complete. She and Eric will move in soon. Once she gets her nurse practitioner's office open and running, she is still planning to use John-Henry's sperm or her egg to create a baby. Ted's old study would make a perfect nursery. A tire swing already hangs from a thick branch of an oak tree, plenty of room to run and play in the shade. The child could start a new future for the Williams family, built on love, or become a casualty of the cycle that shaped Claudia's life, and her father's life before that. She's hoping for a boy. Follow ESPN Reader on Twitter: @ESPN_Reader Join the conversation about "The Greatest Hitter Who Ever Lived On."

text

text

like he accomplished anything.”text