Out Of Thin Air

After a life of football, Joe Namath fears he has brain damage. But he's sold on a dubious treatment -- and wants others to buy in too.

oe Namath takes a deep breath.

He's walking the hallways of Jupiter Medical Center, near his home on the Intracoastal Waterway in Florida. At 72, Namath has a gait that is slightly stooped but determined, his grin craggy but still infectious. He greets the men and women at Jupiter by name, hugs the nurses, asks after family members. He chats with fans who approach, encouraging them to stay healthy.

Namath's eyes sadden a bit as he pauses at a treatment bay where a patient is groaning in distress. "I'll tell you what," he sighs, a familiar dollop of Alabama still sweetening his phrasing five decades after his college days with Bear Bryant, who called him the greatest athlete he ever coached. "You see what some of these folks have to go through and you think, 'There but for the grace of God ...'"

Namath's mission nowadays is to give concussion victims reason for hope beyond divine intervention.

A few years back, he'd begun to think about his own cognitive issues -- they didn't seem serious, but he wasn't sure. He occasionally wondered why he had just walked into a particular room or lost track of his keys. He also struggled with depression. Namath thought about the bone-crunching blows he had taken in his pro career -- knocked cold at least five times, with no treatment except smelling salts. And he pondered the fate of old comrades, struggling through the aftershocks of concussions years after retiring from football, living in fear of losing their minds.

In 2012, he began an experimental hyperbaric oxygen treatment from two doctors at Jupiter. Neither of them was a neurological specialist, but after 120 trips into Jupiter's oxygen chambers, Namath perceived extraordinary improvement in his brain function. And ever since, he's been telling the world -- friends, teammates, reporters -- about the benefits of his therapy. Last September he and Jupiter officials launched the Joe Namath Neurological Research Center. With great fanfare, they announced their goal to a throng of media at the Grand Hyatt Hotel in New York: to raise $10 million for a clinical trial of hyperbaric oxygen on 100 subjects suffering from symptoms of brain damage. Namath would be the lead fundraiser and cheerleader for the project.

The Hall of Fame quarterback has never been conventional, and he knows what he's selling is a leap beyond the fringes of accepted science. To many experts, the endeavor raises serious concerns. But to Namath, the truth is as simple as the air we breathe.

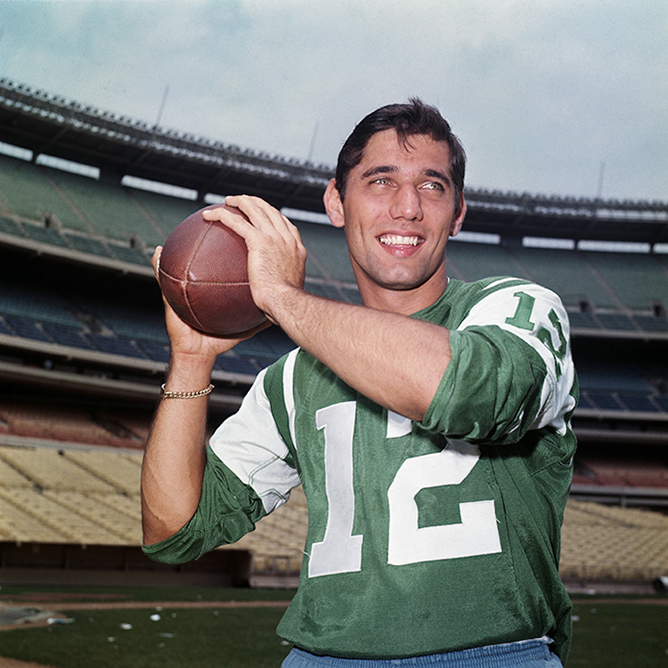

FOR THOSE WHO watched Joe Namath's career up close, it wasn't just his Super Bowl win or his swinging lifestyle that made him a hero but also the staggering pain he endured without complaint. Namath's right knee first gave out while he was still in college. In 1965, the Jets introduced him to the New York media at a news conference at the legendary Toots Shor's. The team orthopedist took Namath into the bathroom to examine him and was horrified at the damage: He thought Namath might never play again even with surgery. Ultimately, Namath had an operation and gritted through more than five seasons without missing a game, but he began seriously breaking down in 1970. Namath battled through torn ligaments and three more knee surgeries, a broken wrist and a separated shoulder, playing a full season just once after the age of 26.

Doctors routinely treated his pain with Percocet and Butazolidin, an anti-inflammatory typically used on horses. They told him to take the medications on a full stomach; concerned about staying in shape, Namath washed them down with Johnnie Walker Red instead. (Later, he switched to vodka.) Many narrative strands are tangled in his tortured relationship with alcohol: a guy out of the steel-mill town of Beaver Falls, Pennsylvania, enjoying the perks of superstardom; a heavy drinker losing his grip on sobriety; a man living like there's no tomorrow because he can't imagine what new hurt the next day will bring.

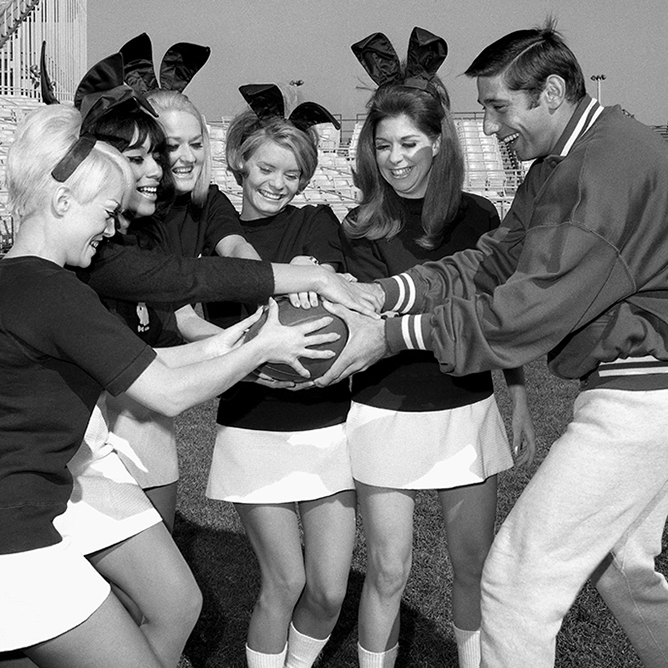

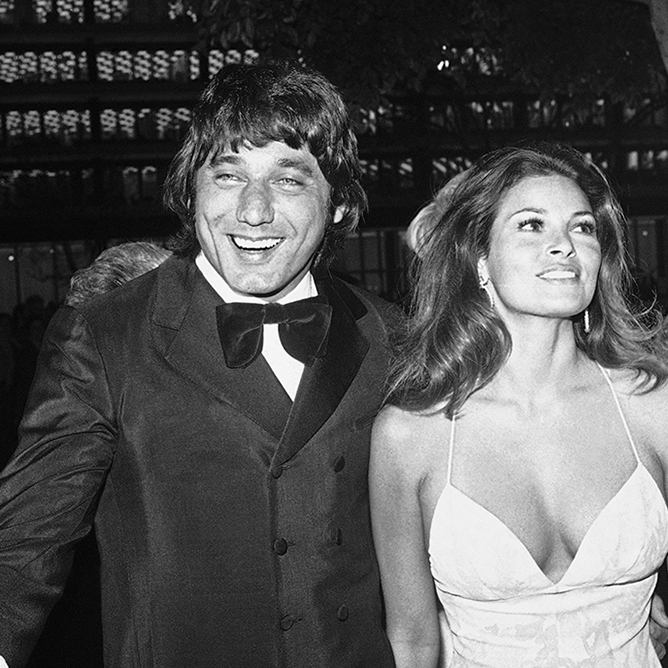

Throughout two decades of alcohol abuse, Namath was still one of America's most sought-after pitchmen, hawking wares from Noxzema shaving cream and Beauty Mist panty hose to Ovaltine drink mix and Brut cologne. He was ready to tone down his bachelor ways after he married Deborah Mays in 1984, and she helped him stop drinking. Namath says he was sober from 1987 to 1999, a period in which he got both knees replaced and was happy to dote on his young daughters.

But after Mays left him for a Beverly Hills plastic surgeon in 1998, Namath eventually went back to medicating his pain with the hard stuff. He bottomed out on Monday Night Football in December 2003, boozily swooning over sideline reporter Suzy Kolber. While one generation of fans remembers Namath for saying "I guarantee it," its kids are more likely to know him by the humiliating catchphrase "I want to kiss you."

After that, Namath sought help: He checked into rehab, and he stopped drinking on Jan. 12, 2004, the 35th anniversary of Super Bowl III. He emerged ready to attend Alcoholics Anonymous meetings and battle through his depression. And it was as if he found himself blinking in unexpected sunlight after a long winter's night. It turned out that Namath's daughters still adored him. His old teammates still wanted to see him. Fans still loved him. The endorsements had dried up, but for the first time in years, Namath could flash his famous smile at himself in the mirror and feel great, so great that it was hard for him to believe he deserved his good fortune. Maybe there was something to the St. Jude medal he had worn for decades, dedicated to the patron of lost causes. There but for the grace of God indeed.

After his physical rejuvenation, Namath began to hear about athletes who couldn't shake the mental effects of their playing days. It's often said that NFL Nation wasn't aware of the dangers of brain injury until recently, but that's not true. Plenty of players, teams and league executives -- and fans too -- suspected for a long time that terrible things could happen to athletes who repeatedly got smashed in the head. In more careless times, however, football shrugged off concussions as a casual inevitability.

In 1979, for example, when Namath was the man of the hour on The Dean Martin Celebrity Roast, comedian Charlie Callas staggered to the podium pretending to be "O.J. Simpleton," a former Jets lineman. "He gets all the glory while we get all the injuries," Callas cracked, referring to Namath. "Look!" he added, taking off his helmet to reveal a giant bandage wrapped around his head. "I've had the same concussion for 15 years. My vision is blurred, my speech is sl-sl-slurred, I g-get dizzy spells and I can't walk straight."

"I've had that for years," the oft-plastered Martin quipped. The crowd roared with laughter.

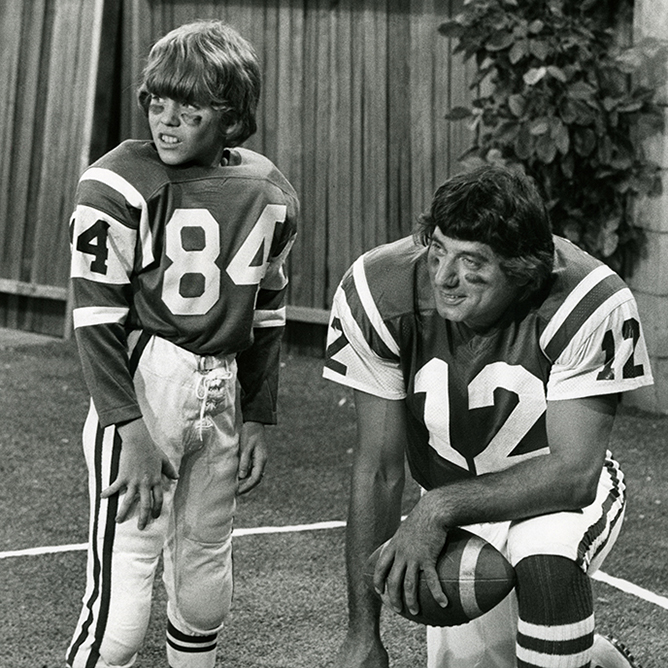

Three decades on, jokes like those hit Namath disturbingly close to home. There was the death of Mike Webster, then the suicide of Dave Duerson, then the sad decline of a real-life O.J. Simpleton named Dave Herman. A Pro Bowl guard for the Jets, Herman blocked for Namath for nine seasons, but toward the end of his career he couldn't remember details of games the next day. His short-term memory problems worsened, and he worried that he might have Alzheimer's disease. Herman had been a regular at Namath's football camp in Connecticut since the 1970s, and a few years ago, he shared his concerns with his old teammate, wondering if he would even be able to return the following summer. "You could just see the fear in his eyes," Namath says.

A lifetime of concussions can lead to a feedback loop of anxiety: If you feel your reasoning power or memory or emotional grip slipping, you begin to worry about what's going on inside your head -- and then worry further about whether you still have enough presence of mind to recognize the changes you're going through. For Namath, the loudest warning bell came in May 2012, when Junior Seau shot himself dead in the chest. Shortly after that, Namath reached out to Lee Fox, a golfing pal from Jupiter Medical Center, where Namath and his family had been treated for minor injuries, to get himself checked out.

As Namath puts it: "It behooved me to find out what's going on with my brain."

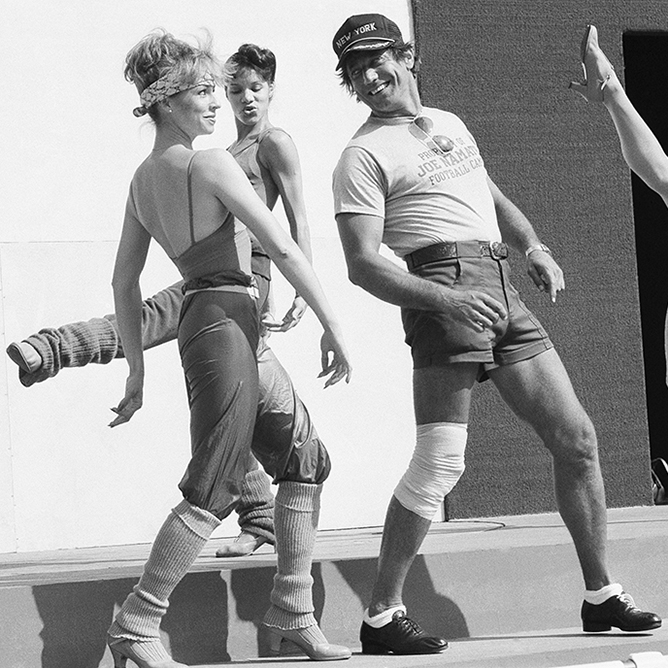

Namath said he was knocked cold at least five times. Russ Reed/Oakland Tribune/TNS/Zuma Press

FOX, A 47-YEAR-OLD Duke- and Washington University-trained radiologist, is the director of imaging at Jupiter, a 327-bed nonprofit hospital in a town booming with retirees and wealthy golfers. (Jack Nicklaus is one of its major donors.) Fox had been thinking for a while about how the medical center might develop new ways to treat brain injury. He knew it made extensive use of hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT), a process in which patients climb inside small chambers to breathe pure, compressed oxygen, flushing cells with extra energy. The Food and Drug Administration has approved HBOT to treat 13 conditions, including burns and carbon monoxide poisoning, but not brain injury. Indeed, while various celebrities, most notoriously Michael Jackson, have sought additional therapeutic benefits from HBOT, the FDA recently issued a consumer update that warned: "Do a quick search on the Internet, and you'll see all kinds of claims ... for which the device has not been cleared or approved."

“It behooved me to find out what's going on with my brain.”

- Joe Namath

Still, Fox wondered if the treatment could help the brain recover from long-term trauma. "A head injury is really just a wound of the brain," Fox says. "I said to myself, 'Why wouldn't it work on a different type of wound?' That's when I became interested in it."

As it turned out, Barry Miskin, Jupiter's director of hyperbarics, had believed in the healing powers of the chambers for a long time. Miskin grew up outside Philadelphia and went to medical school at the Universidad del Noreste in Tampico, Mexico. ("I didn't have the test-taking gene, so I had to leave the country," he says.) A surgeon, he had a long career as a wound-care specialist and in trauma wards, until his life took a sudden detour when his daughter Talya suffered an intrauterine stroke and was born with a seizure disorder. Searching through medical literature and looking into cutting-edge experiments for ways to help her, Miskin hit upon hyperbaric oxygen as a possible method to stimulate damaged areas of the brain. At a local hospital, his wife would hold little Talya as she breathed compressed, purified oxygen through a hood inside a chamber that would typically be used to help divers recover from the bends. Once his daughter started receiving treatments, Miskin says, her condition improved. A decade later, he still believes it has helped. "I believe that after injury, there are areas of the brain that aren't functioning, and the oxygen wakes up those areas," says Miskin, now 61.

Miskin went so far as to install a hyperbaric chamber in his home to continue the treatments. He borrowed money to buy a device from a research outfit in Canada, tracked down a supplier to deliver liquid oxygen to his house and, with the help of a plumber, installed the necessary pipes. "I was going to put it in the garage, but my wife insisted we use the den," Miskin says. "I know that if you look at it from the outside, people think I'm insane. But I'm a surgeon. I can't sit around and wait and see what happens. I need to fix things."

When Fox asked Miskin about treating brain injuries with oxygen, Miskin replied: "I've been waiting for years for somebody to ask me that question." And when Namath called Fox, the two doctors had a test case. "It was a perfect storm," Fox says. "We all kind of came together at the same time for the same purpose."

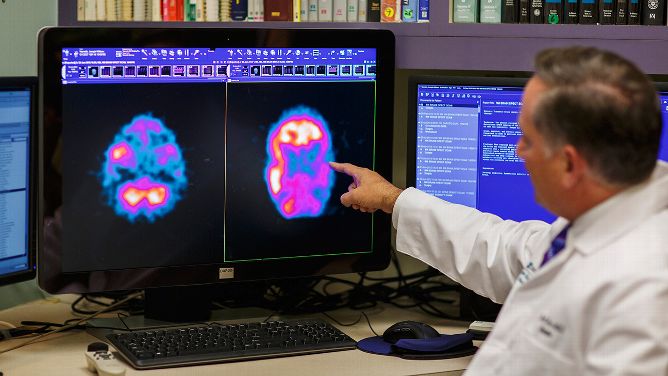

To evaluate Namath, Fox used a SPECT scan, a nuclear-imaging test that shows blood flow in the brain. The results were shocking: Red, orange and yellow images lit up on the right side of Namath's brain, showing normal activity, but the left side was largely dark.

"Well, something's wrong there," Namath thought, but the scans seemed to make awful sense: As a player, he had been hit everywhere, but the hardest shots came from his blind side.

"As a right-handed quarterback getting hit from the left side, [Namath] would typically be hit in the left temporal lobe," Fox says. "When he gets sacked, he falls onto the ground and hits the back of his head. Those are the areas of the brain that we saw had decreased function."

From August 2012 to March 2013, Namath overcame his tendency toward claustrophobia and breathed hyperbaric oxygen for an hour a day, five days a week, following a protocol devised by Miskin. The treatment seemed intuitive to the former quarterback; Namath had learned how to retrain his breathing back in 1977, his last year in the NFL, when his wheels were so bad that he worked out in a swimming pool. "To this day, I stay with it, oxygen in and out, in and out, whatever exercise I'm doing," he says. "A lot of us can go without water for a while and we can fast for a while. But how long can we go without oxygen?"

A scan of Namath's brain illustrates an obvious lack of symmetry between the hemispheres. Melissa Golden for ESPN

After 40 dives in Jupiter's chambers, there was a dramatic change in Namath's SPECT scans: They looked bright and symmetrical. He underwent 120 treatments, and a year later there was still renewed blood flow on both sides of his brain. His cognitive tests improved too. And he felt generally stronger. "The areas of the brain which had decreased activity on the pre-scan now are actually functioning normally," Fox says. "And you can see the results are durable."

"It signals to me that I've been helped," Namath says, looking at his brain scans one afternoon. "I know I'm thankful." So thankful that he decided to give his name to the Joe Namath Neurological Research Center, which launched in September 2014 with Fox and Miskin as co-directors.

At the moment, the center is basically made up of the equipment and staff needed to support Fox and Miskin, who plan to test the effects of hyperbaric oxygen on 100 people suffering prolonged symptoms of brain injury. With Namath's help, they're trying to raise $10 million, largely to offset costs for patients who can't afford treatments, which can reach $75,000 -- and aren't covered by insurance. "The big drawback for all these guys is paying for it," Namath says.

Namath once made a second career from selling almost anything with a wink and a smile, but about hyperbaric oxygen, he is a true believer. He has energetically promoted the Jupiter study, which has a waiting list of nearly 400 volunteers. (Five have been cleared for therapy so far.) And he has recruited donors, helping raise almost $1 million. Jupiter didn't pay Namath for naming rights, nor has he partnered financially with the center, though he has reserved the right to invest if Fox and Miskin someday commercialize their therapy.

"He was basically patient zero," Miskin says. "And because somebody like him came to us, people took notice."

Namath's advocacy has led to glowing publicity, including favorable coverage everywhere from local TV to Good Morning America. Seeing the colors on Namath's post-treatment brain images, one West Palm Beach TV reporter gushed, "The scans say it all!"

Except they don't, not by a long shot.

-

Melissa Golden for ESPN

PLENTY OF RESEARCHERS have been interested in the effects of hyperbaric oxygen, but independent, controlled studies have always returned the same verdict: no lasting benefits for brain trauma in humans.

Most recently, the U.S. military, with more than 233,000 service personnel having suffered brain injuries from 2000 to 2011, has researched HBOT. The Navy and the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency tested differing levels of oxygen for a broad range of possible impacts on 61 Marines with post-concussion symptoms. "There was no evidence of efficacy on the primary outcome ... or any of the secondary outcomes," a team led by David Cifu, national director of physical medicine and rehabilitation programs at the Veterans Health Administration, wrote in the Annals of Neurology in February 2014.

Army-led researchers investigated the effects of hyperbaric treatment on 72 service members who still had concussion-related problems more than four months after injuries, and (they published similar findings in the Journal of the American Medical Association this year. "HBO showed no benefits over sham compression [regular compressed air, as opposed to oxygen]," wrote a group headed by Col. R. Scott Miller, director of the Hyperbaric Oxygen Research Program based at Fort Detrick in Frederick, Maryland.

Cifu, 52, specializes in treating brain and spinal cord injuries and oversees all federal physical rehabilitation programs for veterans. He has heard often from hyperbaric advocates, who have grown into a powerful lobbying force as the off-label use of chambers has exploded in recent years. And Congress, whose members pick up anecdotal stories of hyperbaric success in their districts, keeps ordering the Department of Veterans Affairs to study oxygen for traumatic brain injuries. Now Cifu believes enough is enough.

"There have now been three studies that have been completed and published [by the military]," Cifu says. "Those studies clearly demonstrated no treatment effect for hyperbaric oxygen for either traumatic brain injury effects or for post-traumatic stress disorder. There is no reason to do any further research. This has been shown: They do not work."

The federal researchers, Cifu notes, were looking for any signs of improvement among their subjects. "If they had slept better, if they had felt better about themselves, if they could walk more easily, if their eyes [were] tracking a page better. If anything had worked, these studies would have demonstrated that. And the researchers looked at each of those items individually as well as a group, and we saw nothing."

At a 2014 news conference, Miskin, Namath and Fox announced their plans to study the effects of treatment in hyperbaric oxygen chambers on brain injuries. Bebeto Matthews/AP Images

Outside experts are also concerned about the way the Namath Center has designed its clinical trial. Fox and Miskin plan to evaluate patients with SPECT scans and cognitive tests, give each subject a round of 40 hyperbaric dives and then continue treating those who show improvement. Although SPECT scans are relatively inexpensive and produce visible results, neurospecialists generally don't accept them as a valid gauge of meaningful changes in the brain. SPECT scans measure blood flow, not tissue structure. And because almost anything, from your diet to your mood to your head's position, can change how and where blood flows to your brain, SPECT scans just aren't useful for diagnosing particular kinds of trauma. "The same signature of reduced blood flow is seen in almost any other condition affecting the brain, including depression, attention deficit disorder and many others," says William Barr, a neuropsychologist and professor of neurology and psychiatry at NYU Langone Medical Center. "There is no simple concussion test."

The best studies are double-blinded and controlled, meaning that neither researchers nor subjects know who receives genuine therapy or a placebo. That minimizes researcher bias and helps make sure any changes can be attributed to the treatment, rather than outside factors. But try telling patients paying $75,000 that they might get a placebo treatment. Especially when your website touts the effectiveness of the very therapy being tested, as Jupiter's does. ("It is anticipated that most TBI will show signs of improvement after 40 HBO sessions.") So there aren't any control groups at Jupiter. Everyone will get hyperbaric oxygen.

The Jupiter doctors may address these issues -- with another even bigger clinical trial. "We felt strongly after looking at Joe's results that, at least for these first 100 patients, we would not use a placebo," Fox says. "We could be criticized for that. But if we see the trend that we hypothesize we are going to see, I think expanding our study to address some of those criticisms will certainly be something that we will do." In the meantime, Fox, Miskin, Namath and the patients themselves all have powerful reasons to want hyperbaric oxygen to work. But it's going to be hard for independent observers to tell whether subjects' symptoms are changing specifically because of the therapy.

Questions have been raised about Miskin's work in the past. In 1998, an FDA inspector reviewed the way Miskin was conducting clinical drug research while working at a facility called the Palm Beach Research Center. His records were in disarray. Four months later, the FDA issued a harsh warning, writing, "There are several protocol deficiencies regarding collection of specimens, eligibility criteria of subjects and changes of initial results. ... We remind you that it is not appropriate to collect source data on materials such as paper towels.

“Some people think hope is one of the evils in this world, but hope shines eternal.”

- Barry Miskin

"Continued noncompliance with the regulations governing the use of investigational drugs," the FDA letter concluded, "could affect not only the acceptability of the trial data but also the safety of human research subjects."

Today, Miskin says that run-in was a wake-up call. "As a principal investigator, I'm responsible for the trial. I learned a lot, and I hired a person to oversee all the trials and a clinical supervisor I could trust. I needed to look at everything a lot more carefully. Then the FDA came back in a year, and we got a really good review."

As it continues to promote a therapy most of its colleagues don't find valid, the Namath team cheerfully acknowledges it is working beyond the boundaries of accepted science. So far out there that not one of the three studies by the military has dissuaded them. "You're quoting a study from the same military that said Agent Orange didn't affect anything or cause cancer," Miskin says. "Now they're saying it does."

Namath adds: "When we're talking about God bless America and God bless our government, I think we all have questions on how we operate sometimes, and we scratch our heads on how we can get things in supermarkets, get drugs and all. Come on."

Namath believes hyperbaric treatment has helped him. "I know I'm thankful," he says. Melissa Golden for ESPN

WHEN BELIEVERS NO longer accept that a proposition can be disproved, they leave science and enter the realm of faith. Still, Namath believes in hyperbaric oxygen because he feels better than he did before the therapy. How can that be when research shows no beneficial effects?

The answers probably lie in the fine print of the military studies and inside the chambers themselves. In the research with control groups, subjects who got pressurized, purified oxygen and those who got placebo treatment both showed slight improvement. It turns out that when the mind believes it is getting help, sometimes it can jump-start the rest of the body. "If you have a new way to reframe your symptoms, that's going to set you on a course of recovery," says NYU's Barr. "There's a vicious circle that goes, 'Today I feel better because I took this treatment. My body feels good. My mind feels good. I'm going to be good today.'"

Namath essentially admits as much. "What they do is instill a confidence in the patient," he says. "With Dr. Miskin and Dr. Fox, I've learned to believe what they tell me. You're getting help. I think that speeds up the healing process."

The placebo effect can be incredibly powerful. In widely varying studies, sham treatments have been effective in 30 to 50 percent of subjects who thought they were taking antidepressants, anti-(anxiety medication or post-traumatic stress treatments. And it may be especially strong with HBOT's ritual of supportive treatment. Climbing into a hyperbaric chamber can feel intensely therapeutic: You are sealed into a science-fiction-like capsule while experts in lab coats adjust knobs and nozzles and monitor your every need. "What is clear is that this was a healing environment," said one review of the military studies.

-

However mighty the placebo effect might be, mainstream scientists say it doesn't justify selling hyperbaric oxygen as a method for regenerating brain cells. "Do no harm, that's No. 1," Cifu says. "And you are doing harm when you are providing care for someone with an intervention that doesn't work. By going into those chambers, they are buying into false hope."

So many hurting athletes are so desperate for help that they seek answers not only in hyperbaric therapy but in the larger concussion industry that exists beyond scientific ratification. Enterprising doctors are peddling everything from gyroscopic chairs to secret-sauce supplements. The truth: Recovery from brain injury is hard work with an elusive target, and as yet there are no guarantees for athletes seeking help. "I do think science has a chance to catch up," Barr says. "But we have to realize there's going to be no quick fix."

"Some people think hope is one of the evils in this world, but hope shines eternal," Miskin says. "People prey on that type of hope and that desperation with different things that are out there. You have to figure out what's real and what's not. We have a pretty transparent agenda."

Back in the Jupiter hyperbaric unit, Namath walks amid the chambers, pausing by a shelf of footballs and photos he has signed to thank the staff. "I'm proud -- no, man, I'm lucky that I'm part of the team," he says. "If we're going to put my name on this because of my history in sports, that's fine. That's the role I'll play, and I'll do everything I can to help get the word out."

He adds: "Don't tell me it doesn't work."

of