Dreams Of A Father

Chargers RB Rodney Culver died in a plane crash before his two daughters were old enough to know him. Nineteen years later, they're discovering who he was from the teammates he left behind.

he children wore matching yellow dresses the day Rodney Culver died. Strapped in their car seats, they waited in an idling white Chevy Lumina van at Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport. Their grandma, Wanda Hammond, had brought Cheese Nips and apples to snack on during the trip. She glanced at the clock as the girls fidgeted with their teddy bears. A thunderstorm had just passed.

It was the Saturday before Mother's Day in 1996, and Culver just wanted to get home. He had whisked his wife off for a weeklong cruise on her 25th birthday, but with two toddlers at home, you never really get away. The ship docked ahead of schedule, and Rodney and Karen were excited to learn that they could hop on an earlier flight. ValuJet Flight 592 had empty seats, was set to depart Miami early in the afternoon and would get them home to their kids by suppertime.

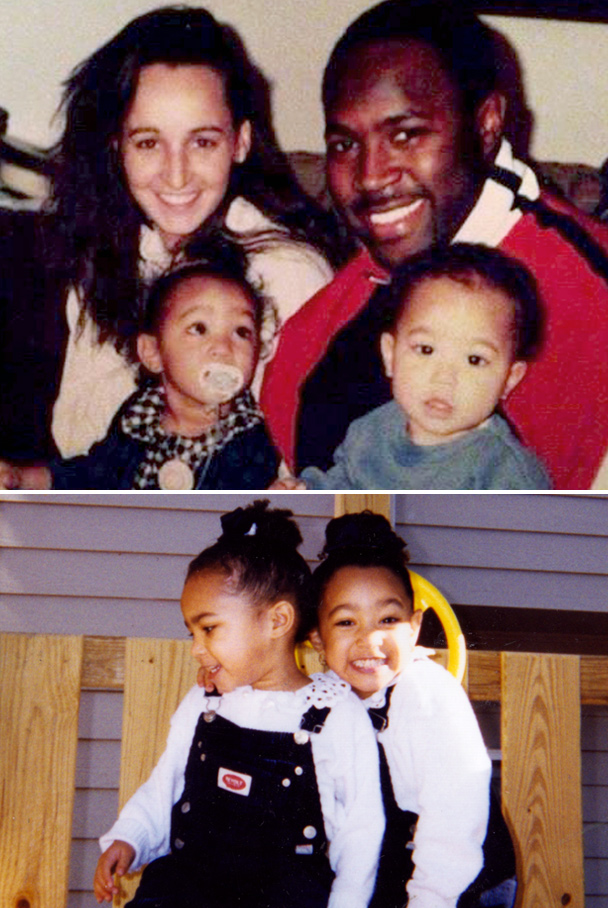

Maybe it was because he never really knew his own father, but Culver doted on his girls. The youngest, Jada, was supposed to be a boy, the ultrasound said she was a boy, but then -- surprise! -- a baby girl came out, and Rodney and Karen couldn't figure out what to name her for two days. They eventually decided on Jada because Rodney thought it sounded unique. Even as they grew, Culver could never just hold one of them. He would grab 1-year-old Jada in one arm and cradle Briana, 2, in the other.

After a lifetime of struggling, he had it all now: the woman he loved from the moment he set eyes on her, a dream job as a running back with the San Diego Chargers and two healthy girls. He bought a house on a golf course in Woodstock, about 30 miles north of Atlanta, under the spruces and pines, with a driveway for a basketball hoop and five bedrooms so his brood could grow.

Just a few days before the trip, Culver told Chargers chaplain Shawn Mitchell that, as much as he needed a vacation, he hated being apart from his kids. But his mom would take care of them, and he'd be right back.

Culver had spent the past five months getting into the best shape of his life. He was 26, strong, fit and certain that this would be his season. "You look like you're ready to go," Mitchell said to Culver before the team scattered for the break.

"Can't wait," Culver responded.

At the airport, as 10 minutes became 30, Wanda Hammond unbuckled the girls so they could roam around the van. Planes landed, strangers reunited with their families, and two hours passed.

Then Hammond noticed people crying. She took the girls inside and was ushered to a back room. Flight 592 had crashed in the Florida Everglades. All 110 on board were dead. She stared down at the children. Just a few hours earlier, Culver had called and asked her to press the phone up to their faces.

"Daddy loves you," he told them.

Chargers RB Rodney Culver and his wife died in a 1996 plane crash, leaving their two young daughters orphaned. Jerome Bettis - Culver's former college teammate and best friend - sits down with them to hear their story and provide insight on their father.

HOW DO YOU miss someone you never knew?

Jada Culver contemplates the question as she pokes at her lunch at a taco house just off the University of Alabama campus. She is 20 and in college now, pragmatic and driven just like her father. She stayed in Tuscaloosa this summer so she could work three internships. Every time she thinks about letting up, she hears a voice pushing her to do better. She believes it's her mom and dad.

As a kid, she yearned to know more about them but didn't dare ask too much. She knew how difficult it was for Hammond. That first year after the crash, Hammond would not allow herself to believe that Rodney and Karen were gone. Their bodies hadn't been recovered from the deepwater swamp, which left her a speck of hope. "They're somewhere in Florida," Hammond would tell herself, "and someone's going to find them and they're going to be OK."

She took their pictures off the mantel, away from plain sight, and hung them in the basement and the girls' rooms. For 15 years, she couldn't watch football -- any football. It reminded her too much of Rodney. Every time a Super Bowl came around, her husband, Thurmond, headed to the basement to watch it on an old TV.

But she had those babies; Lord knows she needed those babies. They gave her a reason to get out of bed and a piece of everything she'd lost. Briana is so much like her mother: her smile, her high forehead, her maternal instincts; Jada is the spitting image of her father.

They moved into the house on Winding Hills Lane, the one Rodney and Karen took so much care planning and building and lived in for only two months. It would be their kids' house. The girls would call Wanda "Mom" because it was easier that way, but Jada knew, staring at the pictures as a little girl, that something bad had happened.

"I don't remember if I was ever sat down and told," Jada says. "I just feel like I knew. I feel like all my life, I've just known."

The story came in bits and pieces. Your daddy played football. ... Your parents loved you so much.

Jada was a young girl, maybe in sixth grade, when she wanted to tell her friends that her father played in the NFL. So she Googled him. She'd never looked up her parents online before. But now she came across the ValuJet crash, and saw their names, and ran to her seat and cried.

Because he was a role player, waiting for his big season, Culver was quickly forgotten in the football world. A framed photo of him hung in San Diego's locker room shortly after his death, and every player who ran out onto the field saw Culver's face before they left that room. But eventually, the picture was packed away. Teammates used to say Rodney Culver was the best man they knew, a person who put God, his family and his team above himself. They vowed to keep his memory going, but they couldn't.

Now Briana and Jada are adults, nearly the same age as their parents when they died, and they have more questions. They want to be able to tell their kids someday about the man who left such an impact on his teammates that he was named Notre Dame's lone captain in 1991. Maybe if they knew more about him, it would help them learn about themselves.

"I'm sorry if I start to cry," Jada says as her eyes well up. "I'm usually good at being able to keep my composure.

"They switched their flight to get home to see my sister and I. If they could've just stayed on their regular flight, who knows? I have thought about that. Would I live in Georgia? Would I live in San Diego? What would I like? What would I dislike? Who would I be?"

After every touchdown, Culver used to point toward the sky, expressing his faith. "He knew if he got injured, he wasn't going to be super-devastated," his mother said. "He knew that whatever He had for him was what His will was." Courtesy Wanda Hammond

THEY MET AT a Powerhouse Gym north of Detroit. The girls know some of the story. Culver spotted Karen Donnelly, a pretty young woman with long, dark hair who worked behind the counter making protein shakes, and asked her out several times. She shot him down each time.

He was drawn to her smile and the fact that she was a tomboy who knew almost as much about college football as he did. She was not in the least bit awestruck that he was this big-time football player on the cusp of the NFL. They'd just be friends, she said, but then they began hanging out with a group from the gym after work and eating late dinners together, and soon, they were more than friends.

Karen had lost both of her parents by then, her dad to lung cancer when she was 13, her mom to breast cancer when she was 19. Her mom's death just about broke her. Her big sister, Julie, tried to fill the void, but it wasn't the same. Karen stopped going to Mass, and Julie wondered whether she'd lost all faith that any good existed in the world.

Then came Rodney. He showered her with love and laughter. He listened to her, and he got her back to going to church, albeit a Baptist service instead of Catholic.

It took a long time for her to introduce Culver to Julie and their brother, Mike. It was the early '90s, and interracial relationships weren't exactly the norm in the Donnellys' predominantly white Midwestern neighborhood. But then Karen took him to Julie's townhouse one night. Culver was nervous, but he shook her hand and flashed a big smile and told her how much he cared for her little sister.

"He was the epitome of a great man," Julie says. "Other than my father, he was probably the greatest man I've ever met in my life."

He was barely in his 20s, but Culver had known for a long time what it was like to be depended on. His mother had him when she was just 15 years old, and three siblings followed, along with a pile of disconnection notices and run-down inner-city Detroit apartments that weren't up to code.

“I don't remember if I was ever sat down and told. I just feel like I knew. I feel like all my life, I've just known.””

- Jada Culver

He wanted to go to Notre Dame not because it was a great football program but because he knew a degree from there would help him land a good job after football. And when the Fighting Irish came to recruit him, Culver wanted Jim Strong, the offensive coordinator, to meet his mom. Culver told him to arrive early in the morning because that's when it was safe in his neighborhood, and Strong lumbered up a flight of stairs to their second-story flat. Strong quickly knew that Notre Dame had to have Rodney Culver.

"He was a beautiful kid," Strong says. "We never had any discipline issues with him. He was always respectful and on time. Anything you asked him to do, he did it with joy."

Culver won a national championship with the Fighting Irish in 1988 and later became the team's lone captain, one of the few in team history. His college roommate, Rod Smith, says Culver was so popular that he received all but seven or eight votes, so there was no sense in choosing any other captains.

Smith used to joke that Culver was a 40-year-old trapped in a college student's body. Classmates would knock on his dorm-room door, seeking advice on girlfriends or school or life. He helped convince star running back Reggie Brooks to stay at Notre Dame when he pondered leaving, and was the recruiting host of future Hall of Famer Jerome Bettis. Culver knew, even back then, that the kid would probably take away his job.

He kept a Bible in his locker, but never forced his religious views on anybody. He was Tim Tebow before Tim Tebow, his mother likes to joke now. After every touchdown, Culver would point to the sky and thank God.

He graduated in 3½ years with a degree in finance. He was careful with his money but generous with it, too. He once flew his mom to Atlanta and handed her the keys to a new house. "This is yours," he told her. He promised Hammond she'd never have to struggle again.

"Mama, you're going to be OK," Culver always told her. "No matter what, you're going to be OK."

Courtesy San Diego Chargers

CULVER SCORED a touchdown in the regular-season finale against the New York Giants, the last game of his life. He played with a broken thumb that day, then was held out of the Chargers' first-round playoff loss.

His best season, numberswise, was his rookie year in Indianapolis, when he was used as a short-yardage back. He ran for 321 yards and seven touchdowns that season. He was cut a year later, then picked up by San Diego. It was just like college, with another loaded backfield that included Natrone Means, Ronnie Harmon and Eric Bienemy. But Culver somehow fit in.

"His skill level wasn't eye-popping," says former Chargers defensive tackle Blaise Winter. "You can't compare him to a Walter Payton or a Barry Sanders. But he was reliable. He seemed to walk around with a certain respect and a certain classiness. He was a gentleman."

That '94 Chargers team was inseparable, with the kind of bond that made everyone know these players were on the verge of something special. They played video games together and hung out in large groups off the field. The chemistry kept building all the way to the first -- and still only -- Super Bowl appearance in franchise history, a game in which they were blown out 49-26 by the San Francisco 49ers. Five months later, a few miles from Joe Robbie Stadium -- the site of that Super Bowl -- Chargers linebacker David Griggs crashed his Lexus into a sign pole and died. An old L.A. Times story said Culver felt terribly for Griggs' 1-year-old daughter.

Culver was gone 11 months later.

Six more teammates have died since. Doug Miller got struck by lightning. The most recent, Hall of Famer Junior Seau, shot himself in the chest. All were under the age of 45. Seven of the eight were fathers.

Now, when one of the 37 surviving members of the team gets a phone call from a reporter, his mind immediately races to the same thing: Not another death. They don't think about that humbling Super Bowl loss so much anymore. All the other losses have been so much harder.

After a few minutes on the phone, Winter recalls something he'd forgotten about for 20 years. It was after a game, in the parking lot where players and their families hung out to have a drink or two and unwind. One time, he watched Culver and his wife and his kids from a distance. He was struck by how happy Culver's kids were to see him, how Rodney and Karen looked so in love.

"I just remember thinking, 'What a beautiful family,' " Winter said. "I was excited for him. From my end of it, maybe there was even a certain, 'I can't wait to have my own [kids].'

"How was he in private? I have no idea. But it seemed to me it was what a family should be, very in the moment of being in love."

Because of the remote location of the Flight 592 crash, rescuers had to access the scene by airboat. Most of the remains of the 110 passengers were not recovered. AP Photo/Rick Bowmer

FLIGHT 592 WAS loaded with people just trying to see their families. Twenty-four-year-old Paul Jordan Smith was headed home to Montgomery, Alabama, to be with his mom on Mother's Day. South Florida mail carrier Charles Fluitt turned down overtime pay that Saturday so he could go on a road trip with his son Marcus.

Marcus Fluitt was a tennis player at the University of Kentucky. He was going home that summer with plans to join the pro tour, and his dad was worried about him driving alone. So he bought a one-way ticket on ValuJet to accompany him. Charles and Marcus were so close that they talked every day. Charles had been Marcus' coach since he was barely old enough to hold a racket.

"We worked hard together," Marcus says. "He helped me through everything."

The families still struggle with what happened in those final minutes on May 11, 1996. Did their fathers and mothers and sons suffer? What went through their minds as they realized the plane was about to crash? Did they think about the basketball games and the Christmas programs they'd miss? Did they wonder how the people on the ground would ever recover?

The NTSB crash report offered clinical details but no solace. At 2:05 p.m., everything was normal. A flight attendant announced that cocktails were available for $3 and beer for $2 and that drink choices could be found in ValuJet's Good Times magazine. Pilots Candalyn Kubeck and Richard Hazen commiserated about the weather. Kubeck had turned 35 the day before.

Less than 300 seconds later, smoke filled the cabin, and shouts of "Fire, fire, fire!" could be heard from female voices on the cockpit recorder. Four minutes later, the DC-9 nosedived into the Francis S. Taylor Wildlife Management Area at more than 400 mph and was swallowed by the Everglades.

The NTSB ruled in 1997 that the plane crashed because of a fire in the cargo hold caused by improperly stored oxygen generators. Inexpensive safety caps would have saved 110 lives.

Culver's family eventually struck a multimillion-dollar settlement with ValuJet's maintenance company, SabreTech.

Hammond was never able to give her son a proper burial. Flight 592 crashed into murky water, filled with alligators and poisonous snakes, and many of the victims' bodies were never found. But one day, Julie Donnelly received word that some of her sister's remains had been retrieved. Karen's right hand had been identified through DNA testing. On that hand was their mother's engagement ring.

Karen was never into material things. Rodney wanted to buy her an engagement ring, but Karen said no, she'd wear her mom's ring. Before the cruise, he surprised her with a ring and a tennis bracelet for her birthday. Julie saw her wearing them when the pictures from the cruise came back. The bracelet and the new ring were never recovered, but Julie got their mother's engagement ring that meant so much to Karen back once the NTSB investigation concluded.

Now she's holding on to it for the girls, along with Karen's wedding dress. Karen married Rodney a few weeks after Briana was born, and she was radiant and beautiful. The dress is more than 20 years old now, and Julie knows her nieces probably won't want to wear it to their own weddings. "But it's my job to make sure if they even just want to keep it for sentimental reasons, then that's it," Julie says. "I will give it to whoever wants it. If they choose to wear it, then it's even more special."

Top: Karen scrapped her dream of being a marine biologist when she became a mom. Below: They hated being called twins, but when they were little girls, Jada, left, and Briana looked alike. Courtesy Wanda Hammond

CULVER WAS ALWAYS a planner. He was already thinking of a life after football, of opening his own business. Maybe he'd run a sporting goods store with his brothers. He never planned for a world in which his two toddlers would be orphans.

After the crash, Julie Donnelly wanted to adopt Briana and Jada and move them to Michigan. Julie and Karen were best friends. They called each other every day, and when Karen was giving birth to Briana, Donnelly was in the delivery room -- but not until the end, because it terrified her to see her little sister in pain. Julie knew what it was like to lose her parents young, and when Karen died, she was determined to do everything she could to make sure Briana and Jada knew who their mom was.

But Hammond didn't just want them. She needed them. "You can look at Jada and see Rodney," Culver's brother Marcus says. "You can look at Briana and see Karen. They're not here, but the images of them are here in their children."

The families amicably decided that the kids would be best off with their grandma, in the house on Winding Hills Lane. At first, the girls were noticeably withdrawn. Briana rarely smiled. Sometimes, she'd scream, "I want my daddy! I need my daddy!"

Hammond would tell her he was in heaven, and that seemed to soothe her. But nothing could placate Hammond herself. Everything was happening so fast then. The phone wouldn't stop ringing with reporters' calls; neighbors couldn't stop bringing casseroles and saying they were sorry. A TV network called and wanted to do a reality show on the family. She unplugged from all of it. The best way she knew to fight the pain was suppress it.

Two binders came in the mail. They were from a group of fans who called themselves the Chargers Moms. They used to make cookies for Culver when he played in San Diego -- he loved them so much that his teammates called him Cookie Monster -- and now they wanted to do something, anything for the family. So they made two thick albums, one for Briana, one for Jada, and collected photos and newspaper clippings of Rodney's football career going all the way back to Notre Dame. A yellow highlighter marked the best paragraphs about their dad.

Hammond was moved by the gesture but stored the albums away. The girls would get them when they were old enough to handle it. But for a long time, the adults couldn't handle it, either.

"It's not like he died of a heart condition," Donnelly says. "He was coming back from a cruise, and his plane went down. You don't have any last words. You never have any closure."

“He was the epitome of a great man. Other than my father, he was probably the greatest man I've ever met in my life.”

- Julie Donnelly, Karen's sister

How do you raise someone else's kids when the pain seems unbearable? You pull together, even though your families are so different. You make sure that the girls go to Michigan at least twice a year, during the holidays and the summer, so that Aunt Julie and Uncle Mike can spoil them, too. You see to it that the girls make that trip, 700 miles each way, even if they have to be driven because you are still terrified to fly.

You give them a normal life, as normal as it can be. You have them play basketball and volleyball and run track. You put them in pigtails and matching clothes until they plead for you to stop.

Those are Briana and Jada's memories: of packs of family members being there for their games; of those god-awful matching purple outfits. They hated being dressed alike. Everybody thought they were twins, and Briana and Jada used to stare at themselves in front of the mirror, trying to convince themselves they looked nothing alike. Hammond did it only because the girls always wound up wanting the same things anyway.

They never quite got used to people knowing their story. Woodstock is a quiet community of 28,000, and they were the family of the football player whose plane crashed. Everybody seemed to know more about what happened than Culver's own kids. In middle school, classmates would walk up to them and hand them their dad's football card. "I have a million cards at home," Briana says.

Briana was uber-protective of Jada, especially when they were teased in school. Sometimes, kids made a point to tell them that Wanda and Thurmond weren't their real parents and suggested that they were craving attention. But they just wanted to be like everyone else.

When the girls were teenagers, Hammond decided they were ready. She pulled out the scrapbooks from the Chargers Moms and handed one to each of them. Jada studied the photos and the accolades. It made her proud. That's her dad. When she's missing her parents, she thumbs through the album.

Briana, now 21 and a college student in Georgia, doesn't look at it much. She has instant access to her dad on the Internet, in YouTube clips from his playing days, but never clicks on them. "I think I'm too sensitive to watch it," she says.

When, as teenagers, they finally knew the whole story of their parents, they mourned them privately. They didn't want to make things worse for Hammond.

Jada leaned on her church's youth ministry group. Most people assume she's OK because it happened so long ago. But she's not always OK. "There are moments when you want them to be there," she says. "When I was really young, I don't think I could comprehend that my parents aren't around. I think it would've been nice to have them at graduation, high school and college. It would've been nice when I have my wedding. My first kid. My first job. Stuff like that."

Hammond gave up years ago on wishing to hear from Culver's old friends. After the crash, she wished some of his teammates would come around. She needed to be around people who'd spent so much time with him, to laugh and hear stories.

Former Chargers coach Bobby Ross used to call Hammond regularly and would send the kids T-shirts and football gear. But beyond that, the dialogue with Culver's old teammates stopped.

"Rodney thought so much of them," Hammond says, "and they thought so much of him. But they didn't come. Sometimes, I think they couldn't really handle it. They said they would do things, but maybe they really couldn't handle his death like they thought."

They never forgot him, though. Rod Smith, who went on to play seven years in the league, still thinks about Culver whenever he watches football. After 19 years, it's still so fresh. In college, they'd stay up late in their dorm room talking about morality, the kind of conversations you have when you're young and your mind is open and your life, it seems, will go on forever.

Smith is a real estate developer now, and mentors a football team in Charlotte, North Carolina. The team, Vance High School, is from a rough part of town. When a player talks to Smith about how he's not getting along with his father, or how hard he has it, Smith tells him about Rodney Culver.

"He's my example," Smith says. "'I've seen a guy go from a worse situation than you're in and graduate from Notre Dame and become team captain. I watched this guy come in with holes in his T-shirts and still grind out A's. I know it can be done. I know it can be done.'"

WHEN THEY GREW OLDER and more independent, Briana and Jada reached out to Jerome Bettis, who had checked in on Hammond and the girls for the first couple of years after Culver's death. They'd heard stories about how close Culver and Bettis were in college, backfield mates and Detroit natives. During school breaks, Culver would give Bettis a ride home and Hammond would cook them dinner.

They tried calling a few numbers they found online, and Bettis' restaurant in Pittsburgh, but could never find the right contact to get ahold of him and eventually gave up.

Hall of Fame running back Jerome Bettis, right, says Culver was a big brother to him during their playing days at Notre Dame. Later this month, he'll take Culver's children to a football game in South Bend, Ind. Melissa Golden for ESPN

EVERY TIME BETTIS has seen the number 5 on a jersey over the past 19 years, he has thought of Culver. Back in their days at Notre Dame, Culver wore 5, Bettis 6. When Bettis was a young man starting out in the NFL, he told himself that he had to keep in touch with his old friend. But by then, Culver had a wife and kids and Bettis' career was taking off, and there was no time.

"When you get kind of pushed in different directions in life, you don't get a chance to reconnect sometimes," Bettis says. "That was a big regret that I had."

When Culver died, Bettis asked the Chargers for his game-worn jersey. He hung on to it for nearly two decades, through 10,000 yards and a Super Bowl. Bettis is an ESPN analyst and lives in Atlanta now, not far from the Culvers, but he never knew the girls had tried to reach him.

When ESPN asked Bettis to interview the girls on camera for this story, he said yes. He arrived on a scorching afternoon in mid-August, days after he'd been inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame. Hammond nervously paced as she waited for him. She went down to the basement, which is sort of a shrine to Culver. To what could've been. There's a framed photo of him from high school, smiling in his cap and gown, and a glass case full of autographed footballs. There's a blue NFL pillow and pictures of a young couple just starting out in life together.

"They had planned on having more children," she says. "Two more, and he was just really excited about it. They would be here all the time when the house was being built, making sure stuff got done and picking out what they wanted."

The basement was unfinished when Rodney and Karen died, so Hammond finished it for them. She's finally at a point where being in this room isn't as hard. It makes her feel closer to him.

When Bettis arrived, Hammond met him in the doorway. She cried and hugged him tight. She told him she loves him.

He introduced himself to Briana and Jada: "I've wanted to meet you guys for years."

“You can look at Jada and see Rodney. You can look at Briana and see Karen.””

- Marcus, Culver's brother

Bettis was the first person outside their family to sit down with them to talk about their father. He knows the funny stories from college. They were kids together. He knew Culver's hopes and fears, maybe not so different from their own now that they're the same age.

Bettis mimicked Rodney's deep and raspy voice, and they were taken aback. They never knew what their dad sounded like.

Where would he start? He met Culver during his recruiting visit to Notre Dame. Bettis was so nervous that trip, a black kid from Detroit at this white university in the middle of nowhere. But then Culver put his arm around Bettis, walked him around campus, and he was suddenly at ease. Culver was his big brother, Bettis told the girls. They'd drive from South Bend to Detroit in Culver's old Honda, laughing the whole way. Culver would call him "Big Daddy," and it drove Bettis crazy because he wanted to be called "The Bus." Culver would check in even after he graduated, and he always hounded Bettis about his grades and anything else he could think of. "I saw you missed that block," Culver would say, and Bettis would fire back, "Don't you have anything else to do?"

The girls had questions for Bettis. Jada wanted to know what kind of hair her dad rocked in college. "I had a Kid 'n Play," he said with a chuckle. "Rodney had a shorty."

Briana asked whether their dad is remembered in the football world, and Bettis said he is, more as a person than as a player. That's why Bettis still clung to his Chargers jersey after all these years. But now he grabbed the shirt and gave it to them. He said it belongs to them.

Bettis asked the girls what they wanted to do with their careers, and when Briana was somewhat vague, he told her she needed work experience and a plan. It sounded like a conversation two young men might have had somewhere in Indiana more than 20 years ago.

He scribbled his phone number and email address on a pad of paper and included a note. "Call if you need anything."

The girls have never been to Notre Dame. Bettis couldn't believe that. So on Oct. 17, they'll travel to South Bend to watch the Fighting Irish play USC. And Bettis will put his arm around them and show them the way.