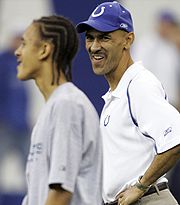

INDIANAPOLIS -- Once he's gotten off the phone with his friends for the night, it's not unusual for Eric Dungy to chat with his dad. The father-son moments allow Tony Dungy to ask, you know, how things are going, which young lady Eric is going with, those sort of things. Dad wants to see if there's anything on Eric's mind and if there's any fatherly advice he can offer.

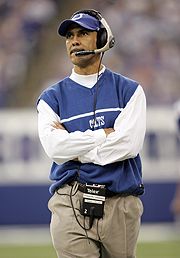

As coach of the Indianapolis Colts, Tony Dungy makes his living making adjustments. Some are subtle. Parenting and coaching are a lot alike in that way. As he and his family cope with the toughest loss of their lives, that of their son and brother, James, Tony Dungy is taking the necessary steps to see that it doesn't happen again. Those steps don't have to be huge. In this case, they amount to a simple stroll into the other room.

"Sometimes I don't want to listen but I know what he's trying to do," says Eric Dungy, 14. "He wants to have a relationship, he wants me to know I can talk to him when I need to."

"I probably think about my kids more," Tony Dungy says. "I worry about them more, especially with the letters I've gotten about what teens and young men are going through, the pressures on them."

And with good reason. In the early-morning hours of Dec. 22, 2005, Tony and Lauren Dungy lived a parent's worst nightmare when they learned their eldest son and second of five children, 18-year-old James, had been found dead in his suburban Tampa, Fla., apartment. In February, James' death was ruled a suicide.

"As a parent you'll never have any greater pain in your life," Colts president Bill Polian says. "Anyone who's a parent dreads that call in the middle of the night. I have four grown children and I still dread it."

When Dungy told Polian the news, "[I thought], 'Oh my God. Oh my God, what a tragedy.' I think that's what I said. … The hardest punch you've ever taken to the gut doesn't compare. It's something you never want to relive."

And yet Dungy is able to live with what other parents who have lost children often describe as an unbearable pain because of his faith. Great coaches have the ability to see the game differently. Great men are able to view life's unfortunate circumstances from a unique perspective. Dungy's doing that.

| DUNGY ON 'SPORTSCENTER' |

| Tony Dungy recently sat down with ESPN for an exclusive, in-depth interview to discuss the aftermath of his son's death. The feature will air Sunday during SportsCenter (11 p.m. ET). |

Last season, when first-year Colts defensive tackle Corey Simon and his wife experienced a personal tragedy, Simon and Dungy had a talk in the head coach's office. Dungy has an open-door policy; his players feel like they're talking to their father rather than their coach. Dungy reminded Simon that God's will is perfect. When Colts middle linebacker Gary Brackett lost his father, mother and brother over a 16-month period ending in February 2005, Dungy told Brackett that he was in a position to inspire others by holding his head high in the face of his adversity. Dungy put his arm around running back Warrick Dunn when they were together in Tampa Bay and Dunn was trying to cope with the death of his mother while also balancing a career and raising five siblings. Lauren Dungy often would accompany Dunn on parent-teacher conferences -- that's how extended the Dungy family is. We could go on for days with stories like this.

Says Dunn of his former coach, "He never gives you room to question his faith."

Dungy tried to offer encouragement to former Bucs quarterback Trent Dilfer three years ago after his 5-year-old son, Trevin, died of heart disease. Still, Dungy, though he's one to practice what he preaches, admittedly had his doubts about whether he'd even be able to handle the loss of a child.

"I said, 'Trent, we've been through a lot, been through ups and downs, tough times, and I think I could go through just about everything you've gone through, but I couldn't go through that,'" Dungy said.

Dungy said the same thing when he and Dilfer talked before the Colts and Dilfer's Browns met in Week 3 last season. On both occasions, Dilfer assured Dungy that he could and would endure, for their God would provide Dungy the strength necessary.

Dilfer has never been more on target. Since James' death, Tony Dungy has displayed nothing but his usual class, dignity, grace, and poise -- be it in eulogizing James at his Dec. 27 funeral, addressing the public immediately afterward and at speaking engagements, or just in how he handles himself day to day in those moments when few are watching.

"The day it happened," Eric recalls, "he was sad, but he wasn't a wreck or anything. He just kept his faith in God."

"The only word I can think of to describe it is 'extraordinary,'" Polian says.

But because so many (maybe millions) are watching, Dungy believes -- just as he told Brackett -- that God has placed him in this position not for him and his family to suffer but so they can be an example to others, a testimony.

"Our God is bigger than our pain," Dilfer says.

Dungy could see God at work in the letter informing the family that two people can literally see now because they received James' donated corneas. In January, Dungy managed to pen an encouraging letter to Rhonda Brown, wife of former NFL defensive back Dave Brown, after her husband died at age 52 of a heart attack while playing basketball.

"I [wrote], 'I don't know exactly what you're feeling but I know that the Lord can get you through it.' That's the encouraging thing, that I can say to people now, that you'll make it," Dungy says.

Day by day, blessing by blessing, Dungy can make more sense of something that seemed so senseless just seven months ago. According to Lutz, Fla., police, James' girlfriend, Antoinette Anderson, said she'd discovered James' body and that the 6-foot-7 Dungy, who was attending Hillsborough Community College, had hanged himself from a ceiling fan using a leather belt. James would have turned 19 on Jan. 6.

Listening to Dungy put it into perspective, it's easy to understand how he's taken his many difficult professional losses in stride. The man is simply unwavering in his beliefs. He can be calm in even the worst storms. Nothing, it seems, can shake him from his foundation.

"The Lord has a plan," Dungy says. "We always think the plans are A, B, C and D, and everything is going to be perfect for us and it may not be that way, but it's still his plan. A lot of tremendous things are going to happen, it just may not be the way you see them.

"You may not win the Super Bowl. Your kids may not go on to be doctors and lawyers and everything may not go perfectly. That doesn't mean it was a bad plan or the wrong thing. It's just like a football season. Everything's not going to go perfect. You're going to have some losses that you're going to have to bounce back from and some things that are a little unforeseen that you're going to have to deal with. It's how you work your way through things."

Dungy's way of coping with James' death is to take something of a head coach approach and not spend too much time on the last play, if you will. He's focused on the larger picture and keeping his family together rather than trying to piece together the puzzling circumstances surrounding the death of his son, who Dungy says was the most "sensitive" of his children and who is described as a pleasant young man who seemed to love life. Among the many lessons Wilbur Dungy taught his son Tony was not to dwell on the past but to learn from the experience and focus on what he would do next. Wilbur Dungy taught Tony that life does indeed go on -- even after the death of a loved one. In fact, when Wilbur Dungy died June 9, 2004, from leukemia, Tony was at minicamp practice the next day because his father loved going to practice and that's what he'd have wanted Tony to do: to go on.

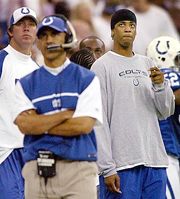

When James Dungy died, Polian told Tony to take all the time he needed, until March if necessary, to work from Tampa if he wanted. Polian insisted that the Colts would make it work whatever he decided. The week he took off -- and this is typical Tony -- Dungy was more concerned about how the team was handling everything than he was himself, assistant head coach Jim Caldwell says. Polian says when Dungy returned with Eric to the facility the Thursday before the final regular-season game, it brought a sense of normalcy to the organization. Dungy, who couldn't imagine how to deal with James' death without the grind of the season to serve as a distraction, says he never considered stepping down as head coach.

Amid speculation about his long-term future, Dungy told Polian he'd be back before Polian could even broach the subject. "The happiest moment that I've had with the Colts," Polian says, "because I couldn't imagine going forward without him."

Dungy says his wife is having a harder time than he is; James (everyone called him Jamie) and his mother were quite close. (Tony politely declined an interview request on Lauren Dungy's behalf.) It's emotional for Lauren, Tony says, whenever she drives past one of James' old schools or near a park. Or when she's alone with her thoughts when the couple's younger children, Jordan and Jade, are asleep and Tony isn't home. Or when they're in a store and a clerk who was a schoolmate of James' wants to share stories about him. Theirs is a pain to which only parents who have lost a child truly can relate.

Somehow, Tony Dungy can accept the possibility that he may never truly come to know why James is gone. It's hard sometimes, though, moving on without his oldest boy. When Tony and Eric attended the Big Ten men's basketball tournament, Tony's thoughts turned to James and he couldn't help but think that he should have been there with them. He thought the same thing at the league meeting in Orlando, Fla., and on a trip to Tampa's Busch Gardens the family took during the playoff bye week, a vacation that originally was to be a fishing trip with just James and Eric. James crossed Tony's mind when he emerged from the tunnel before the emotional finale against Arizona.

"People say you never really totally lose that," Dungy says.

Because the Dungys are such a close family, one that always travels together, and because Tony is such a committed father, it made James' death all the more heartbreaking. And shocking.

"I don't know that we will ever really have any answers," he says. "We've heard from a lot of people … who have been in the same situation and … you never really know for sure. And so we've just tried to look forward and move forward and not really look back too much and search for answers."

He adds, "You never really know why. … That's what most of the people I've talked to, the parents, they're still trying to figure out. Why? What happens that your son or daughter thinks is so difficult that they can't talk to you or they don't? That's what you can't figure out. That's always tough. And then you think about, 'Could I have done something different? What if, what if, what if?' You look behind you, but there's nothing really you can change."

"You go through that, 'How could you do this to us?' Then common sense prevails and you realize he's not trying to hurt you," Dungy says. "Something was really hurting … inside of him. That's one of the emotions you go through [anger]. You feel sorry for yourself and you're hurting more for yourself than you are for him. Then you realize that's not the right way to go."

Dungy acknowledges that he has had thoughts of, "Why me?"

"You start out like that, but then you realize it's not just you," he said. "It's much more common than we could imagine."

He's learned that it's all too common among young men who seem to "have it all." Dungy says he has had correspondence with at least a dozen families who are dealing with losing a child to suicide who was not considered "at risk."

"It's not the kids who are struggling or that had issues that we would think were issues," Dungy says.

Perhaps Dungy's only real regret as a father is that he hasn't been there for his children as much as his late parents were for theirs. As well as Tony can remember, Wilbur and Cleomae Dungy, both teachers, attended every event, every game when he was growing up in Jackson, Mich., and were always home on weekends. Tony's career has kept him from doing the same. Still, he's always prioritized his role as a husband and father ahead of his job and encourages -- much the same way mentors Chuck Noll and Dennis Green did with their teams -- his players and staff to do the same.

Dungy is as committed to his work with All-Pro Dad and Family First as he is to improving his 107-66 career record and capturing that elusive Super Bowl title, though the latter never at the expense of quality time with his family, which he vows will not be defined by this recent tragedy. Dungy takes his children to school and gets out of the office early whenever he can. No first in, last to leave stuff with him. His primary advice for parents -- fathers in particular -- is to just be around and available to their children.

"He sets a tone," Caldwell says. "I think you'll find that every one of us has become a better father being around him."

Of course, Tony Dungy will be spending Father's Day with his children. The Dungys probably won't do anything special. It'll be something simple, something outdoors. Wherever he is, naturally he'll think of his father and reflect upon the profound impact he had on his life. And he'll think of Jamie, and how his life ended much too soon.

But Father's Day won't be a sad day for Tony Dungy. Despite his family's pain, he is able to experience peace, the kind that, as Dilfer put it in paraphrasing a verse from Philippians, comes only from God and transcends understanding. Their faith teaches Dungy that Jamie is in a better place now, that others somehow have and will continue to be blessed by his death, and that someday they'll be together again.

"I've said all along that God is in control," Tony Dungy says.

"I have to believe that he's in control here, too."

Michael Smith is a senior writer for ESPN.com. Contact him here.

Comments

You must be signed in to post a comment