The Spirit Of A Legend

Sixty-three years after Jim Thorpe's death, his sons still believe their father isn't at rest.

IN A CLEARING on a grassy hillside near a two-lane highway in eastern Pennsylvania lie the bones of Jim Thorpe, the man considered by many to be the world's greatest athlete. Fashioned of polished stone the color of red riverbank mud, his tomb is oblong and almost 6 feet tall. A truck rumbles past, then another. The rustle of wind blows low across the glade and through a line of trees. Few people stop to pay respect to this legendary Native American.

The crypt is at the edge of a small town Thorpe was never known to visit, a place with which he had no known connection. The community, Jim Thorpe, Pennsylvania, took his name to claim his body, and its residents think their town has won a decades long battle to keep his remains as a tourist destination. Thorpe's sons, the last of his living children, think his spirit wanders the earth in sorrow because he has never had a proper ceremony for the dead. They say they will fight for his remains until they can return him to his original home in Oklahoma.

Jim Thorpe, Pa., is named after one of the greatest athletes ever, but also one who never set foot in the town. In a piece first reported by Jeremy Schaap in 2004, a family and a town dispute the remains of a beloved figure.Danny Wilcox Frazier/VII for ESPN

ONE THOUSAND four hundred eighty-two miles southwest of Thorpe's grave, his son Richard walks slowly through the living room of his small home, tucked off a narrow, gravel road near Waurika, in the stillness of southern Oklahoma. Richard Thorpe is 83, thin and halting. His grip is weak. His voice is low and rounded, as if his words are flowing over pebbles stuck in his throat. For 63 years, he says, the spirit of his father, Wa-tho-huck, "light after the lightning," has been wandering the earth without peace. Richard Thorpe and his brother, Bill, who is 87, want to bring him back to these dusty hills and give him a proper burial where he wanted to be: with his family, where he was born.

"He lives with me each day from the moment I wake," Richard says, motioning toward one wall of his cream-colored living room. He stares through thick eyeglasses at a photo of himself and his father, taken in black and white in the mid-1930s. Richard was a bashful boy at the time, standing on a front porch, wearing a Native American headdress. The wide hand of his father lies across one of his narrow shoulders. Richard Thorpe struggles to speak; not long ago, he suffered a stroke. "To everyone else, he was this famous man. He'd walk into a room, and everyone would turn and look," he says. "To us, he was Dad. Just plain Dad."

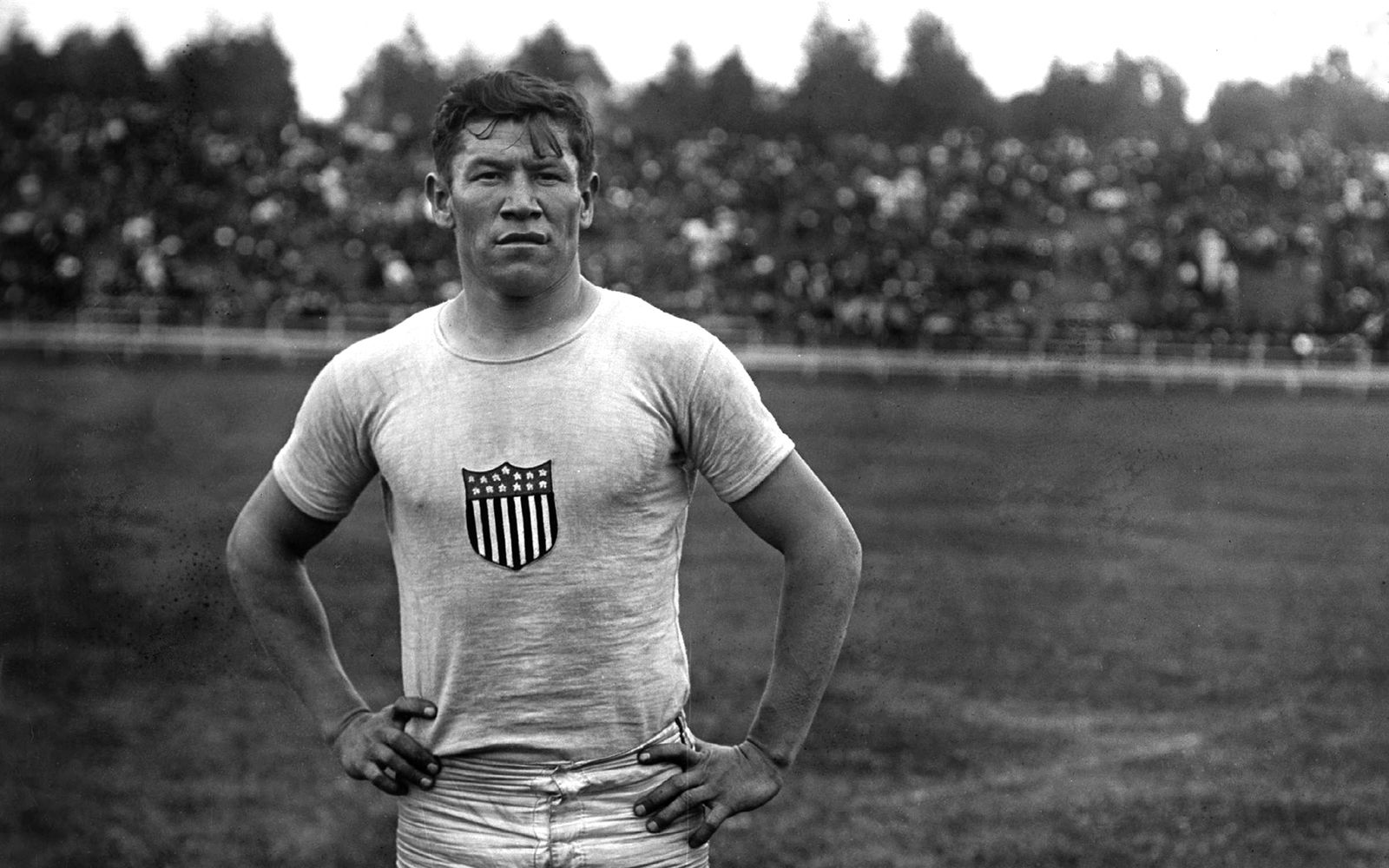

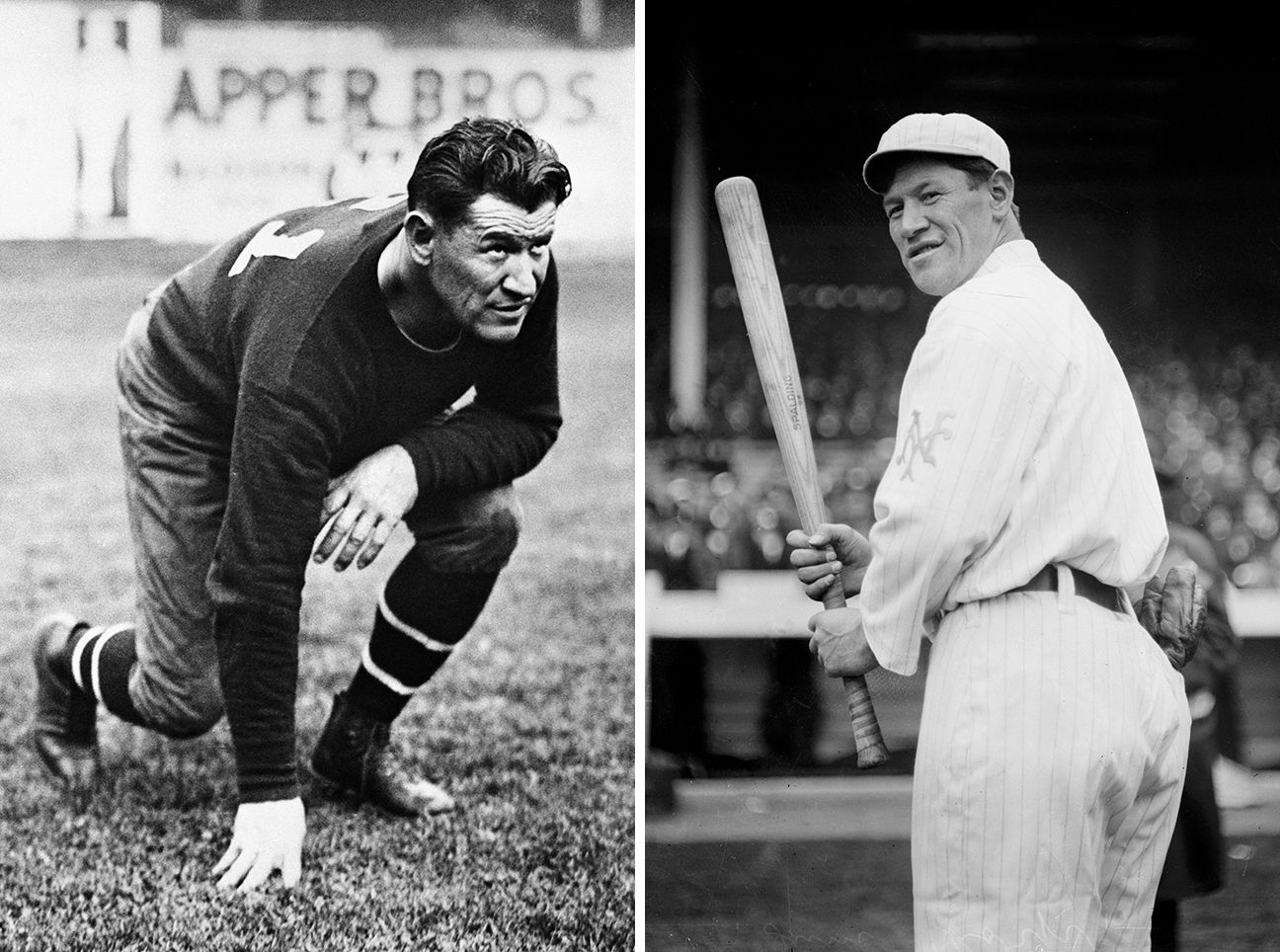

On other walls in the room are more images: paintings and lithographs of Jim Thorpe, with his rugged face, his wide neck and his quick, sinewy muscles. He is motionless, yet full of energy, as he plays college football in the thick woolen uniform worn at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania, as he races down a track at the 1912 Olympics and as he gets ready to bat for the New York Giants. On a bookshelf in Richard's living room are medals and statues, each inscribed with the name Jim Thorpe.

One hundred twenty-five miles farther south, Richard's brother Bill sits in his living room in Arlington, Texas, also surrounded by paintings and photographs of their celebrated father. Bill, a former parts-supply supervisor in the aeronautics industry, and Richard, a retired purchasing agent for the state of Oklahoma, share Jim Thorpe's flinty eyes, his determined jaw and his sturdy shoulders. The sons are not given to emotion, but when they speak of their father's soul, they are stricken, particularly when they recount a cold spring night in April of 1953, which still has the sharp sting of a fresh wound. That was the night their father's body was snatched away during his funeral.

"Time is getting short," Bill says, speaking about himself and his brother. They want to be alive to see their father come home. If they hope to win the battle for his bones, they must do it now. "His spirit isn't rested," Richard says. He forces the words to come. "The people of his tribe never finished the burial the way it must be done. He was taken from us. We never finished."

Jim's third wife, Patsy, showed little interest in, and sometimes even disdain for, tribal tradition. Bettmann Archive

IN THE LOW, rolling hills just outside Shawnee, Oklahoma, a bulky, dark casket lay on a blanket-covered bench in the middle of a ceremonial hut covered with canvas. Inside the coffin was Jim Thorpe, his head pointed to the west, where the spirits of the properly buried go to live.

Under his wire-rimmed glasses, blue paint swirled around his eyes. He was dressed in a buckskin jacket and leather moccasins. "He had beadwork draped around his shoulders," Bill Thorpe says. He clutched tobacco that had been blessed by the tribe. Next to his body lay an eagle's wing. Food would be placed inside his casket before it was closed, enough to keep his spirit nourished on its long westward passage to the other side.

The sons and others remember that it was dark. The hut was filled with family and members of the Sac and Fox tribe. Smoke floated in the air. Metal pots hung over a fire. The pots were brimming with beef, chicken, venison, corn and pumpkin.

Tom Brown, a tribal elder, started the prayers. Patsy was Jim Thorpe's third wife, and she had shown little interest in, and sometimes even disdain for, tribal tradition. She wouldn't have been permitted inside for long regardless; a spouse is not allowed to spend much time with a deceased loved one, as it can disturb the spirit. "All of this must be done properly, in the traditional way," says Sandra Massey, the tribe's historic preservation officer. It has been this way since before white men set foot on North America. It is important to feast on the stew bubbling in the pots, and then to sit with the body in the darkness past sunrise. Sometime before noon the next day, Jim Thorpe's coffin was to be carried out of the hut through a door facing west.

His body would be taken to a mausoleum while details were completed for a memorial on a family burial plot nearby. Meanwhile, Thorpe's spirit would travel on an extensive journey where it would be tested. His spirit would have to fend off distractions, and it would be asked to give an accounting of his life. According to Sac and Fox beliefs, failing to complete a burial observance has terrible consequences. "If you don't [finish], he is earth-bound," Massey says. "He is stuck here, stuck on this plane."

As Brown prayed, Patsy burst into the hut.

Richard and Bill and the rest of Jim Thorpe's living offspring looked up, startled. They were the children of his previous two wives. Patsy's relationship with the four sons of Thorpe's second wife, Freeda, was strained. "A royal piece of work is what she was," Richard says. "To me, that woman, she seemed just mean, all the time." Adds Bill: "The way she looked at it, people answered to her. She didn't answer to anyone."

Patsy had brought the police and a few men in suits.

"He's too cold!" she declared. She ordered the men to take the coffin.

"You can't do this!" Bill shouted. "No! Absolutely no."

Jim Thorpe's daughters, Grace, Gail and Charlotte, yelled: "No! No!"

So did other members of the tribe.

But the police, Bill says, stood nearby "while the hearse people took the body and the casket."

Neither Richard nor Bill remembers Patsy saying more.

The two sons recall a sense of sheer helplessness. Patsy was white. Whites held virtually unquestioned authority on native land, especially in places like rural Oklahoma. The tribe members in the ceremonial hut had been conditioned to acquiesce.

"The feeling was like this," Bill says. "'What can we do?'"

Jim Thorpe's children and members of the tribe never saw him or his coffin again.

"The way it happened that night -- hell yeah, I'm still angry," Bill says. "That kind of hurt doesn't go away."

With the exception of athletics, little came easy to Jim. Bettmann Archive

THE BATTLE OF Little Big Horn and the Nez Perce conflict were over, but the Massacre at Wounded Knee was still to come, when Jim Thorpe was born on May 28, 1887, in a wood cabin near Shawnee, on what was called an Indian allotment.

The United States was suppressing Native American religious practices, banning reservation residents from leaving without permission, putting agents in charge of the welfare of their children and sending them to Indian boarding schools hundreds of miles from home to forcibly assimilate them into white culture.

Hiram Thorpe, Jim's father, was part Sac and Fox and part white. Charlotte Vieux, Jim's mother, was part white and part Potawatomi. As sometimes happened to Native American children, Jim Thorpe was baptized a Catholic and given a Christian name, Jacobus Franciscus. But he came to identify as a Native American and followed Sac and Fox ways as much as he could.

"Dad was connected to the land," Richard says. "It gave him peace. Made him strong."

By age 8, he was an expert fisherman and hunted deer and turkey. By 10, he was breaking wild horses. He liked to spend days alone, studying the movements of animals.

Apart from athletics, little came easy for him. His twin brother, Charlie, died of smallpox as a child. By his midteens, Jim had lost both his parents. He was sent away to a series of Indian schools. "Relentless and brutal places," says Philip Deloria, a professor of history and American culture at the University of Michigan. "They were trying to beat the Indian out of these kids, and the kids were often paying with their lives."

Thorpe gained national attention at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania, where he played football for Glenn "Pop" Warner. In the first game of his breakout sophomore season, Thorpe, a pounding defender and slashing back, scored six touchdowns in two quarters. In 1912, Carlisle played Army at West Point, where George Custer is buried. "Your fathers and grandfathers fought their fathers," Warner told his team. "These men playing against you today are soldiers. They are Long Knives. Tonight we will know if you are warriors."

The game was a demolition. Carlisle won, 27-6.

"Standing out resplendent in a galaxy of Indian stars," reported The New York Times, "was Jim Thorpe, recently crowned the athletic marvel of the age. At times the game itself was almost forgotten while the spectators gazed on Thorpe, the individual, to wonder at his prowess."

Thorpe, 6-foot-1 and 185 pounds in his prime, went on to become the nation's biggest draw in the early days of professional football. He played baseball, as well, including six seasons in the major leagues. He batted .252 in his career with the New York Giants, Cincinnati Reds and Boston Braves, including a .327 season in 1919.

But it was during the 1912 Olympics that he gave people reason to regard him as the world's best athlete.

"He could really move," Richard Thorpe says. "He was too old to show it by the time I came around, but sometimes you could see it. He could still have that ease." From left: Bettmann Archive; Bain News Service/Interim Archives/Getty Images

He hardly trained. When he traveled to Stockholm aboard the S.S. Finland, he was relegated to sleeping in steerage while others on the U.S. team enjoyed upper-level staterooms. But he won a gold medal in what was then the pentathlon, which combined a long jump, javelin throw, discus throw, 200-meter race and 1,500-meter race. Except for finishing third in the javelin, he placed first in each event.

He took a second gold in the decathlon, to this day considered the ultimate test of overall athletic ability. He beat his closest challenger by nearly 700 points, setting a world record of 8,412 points -- a record that would stand for 20 years.

Few knew it at the time, but just before the decathlon's 1,500, Thorpe had reached into his bag and found his shoes were missing. He went to the locker room and found a replacement shoe for his left foot. Then he dug in a trash can and found one for his right. In this mismatched, ill-fitting pair, he won the race.

"He could really move," Richard Thorpe says, looking up at a painting of his father in Stockholm. "He was too old to show it by the time I came around, but sometimes you could see it. He could still have that ease."

Jim Thorpe's dominance at the Olympics, together with his feats in football and baseball, turned him into an icon. Deloria calls him "the first pop star" in American sports. In 1951, The Associated Press asked sports reporters and broadcasters to pick the greatest athlete of the half-century. Babe Ruth was second. The winner, by a large margin, was Jim Thorpe.

When he won his gold medals, Thorpe was not yet an American citizen (most Native Americans didn't receive full citizenship until the 1920s) and he struggled to balance white expectations with his identity as an Indian. He was "part of the outside world, but he always felt a distance from it," Bill Thorpe says. "When you grow up the way he did, that's just the way it was."

Thorpe drank too much. He worked to control it, but Bill says the combination of alcohol, bars and a nettlesome public sometimes led to fights. His first child, Jim Jr., contracted polio at age 3 and died in his arms. He and his first wife, Iva, had three more children -- daughters Gail, Charlotte and Grace -- before she divorced him, citing desertion. He had four sons with Freeda: Carl, Bill, Richard and Jack.

Richard and Bill remember good times with their father. Roughhousing, fishing off the piers of Southern California, trips to San Diego. But he "wasn't easy," Bill says. "I think I still have a few scars on my butt from when he took a belt to us." After 15 years, Jim and Freeda were divorced in 1941.

For much of his adult life, a shadow hung over Thorpe. In 1913, the Amateur Athletic Union (AAU) retroactively deemed him a professional (he had left Carlisle for a short time to play semi-pro baseball) at the time of his Olympic competition and famously stripped him of his medals. He was an easy target: Native American, and not well educated.

Thorpe's playing days extended into the late 1920s. Afterward, he bounced around. He lived in California, Nevada, Michigan, Illinois and Florida. He coached, sold cars, joined the Merchant Marine and became a security guard at a Ford plant. He owned bars, judged dance competitions and dug ditches. He drove a Model T across the country, hunting dogs at his side, and delivered speeches extolling physical exercise. He dressed in Native garb and lectured schoolkids and community groups on the history and potential of his people. In Hollywood during the 1930s and '40s, he found his steadiest foothold, playing bit parts alongside Errol Flynn, Mae West and Buster Keaton.

In 1945, Thorpe married Patsy, a dark-haired nightclub singer. She boasted of playing piano in one of Al Capone's Chicago bars. Kate Buford, author of "Native American Son: The Life and Sporting Legend of Jim Thorpe," says Patsy was intelligent and witty but "also an alcoholic who was manipulative, mercurial, predatory and sometimes cruel and unbalanced."

Jim and Patsy Thorpe had a stormy relationship, full of hard drinking and sometimes fights. She managed his business affairs aggressively: booked his speaking engagements, negotiated with movie studios and badgered reporters to write about him.

But they had trouble holding on to money.

By the early 1950s, they were living in a trailer on the flats of suburban Los Angeles. He underwent surgery for lip cancer. "We're broke," Patsy told reporters at a news conference afterward. She thanked doctors for operating free of charge.

"Jim has nothing but his name and his memories," she said. "He spent money on his own people and has given it away. He has often been exploited."

Thorpe suffered a series of heart attacks. His children prepared for the worst. One afternoon, Jim Thorpe began speaking about what the family should do with his body if he died. Bill says his father "wanted to make sure he was buried in Oklahoma. On Sac and Fox land." Bill and Richard Thorpe say he repeated the request to others.

Jim Thorpe died on March 28, 1953, of another heart attack.

The family -- including Patsy, Bill says -- agreed to take his body home to the plot near Prague, close to the Indian allotment where he was born. There would be a traditional Sac and Fox rite, then a Catholic Mass. Afterward, his body would be kept in a mausoleum until Oklahoma built a Jim Thorpe memorial, which was being proposed by a state commission for construction on or near the burial site.

Danny Wilcox Frazier/VII for ESPN

Danny Wilcox Frazier/VII for ESPN

Danny Wilcox Frazier/VII for ESPN (3)

WHEN PATSY THORPE left the hills of Shawnee with her husband's body, she went ahead with the Catholic Mass, then took him to a local mortuary. Plans for a Jim Thorpe memorial were falling through. It was budgeted to cost at least $25,000 in public money, but Gov. Johnston Murray said the state couldn't afford that much and refused to fund it.

Without consulting her husband's children, Patsy began to look elsewhere.

"Moving my father's body around like some sort of commodity," Bill says.

Biographer Bob Wheeler, author of "Jim Thorpe: World's Greatest Athlete," interviewed Patsy during the late 1960s, a few years before her death. Wheeler says Patsy told him she began shopping the body when Oklahoma refused to pay for his memorial. "She was so incensed that she just lost it," Wheeler says. "It would take a master psychologist to ascertain her motivations. Her personality was extremely complex."

Patsy looked east. There might be money in Pennsylvania, where Thorpe had gained his initial fame playing football for the Carlisle Indian school. Town fathers picked out a location for a memorial but their plans fell through. The head of a local committee has since said Patsy's dollar demands were too steep.

Next, Patsy went to Philadelphia, where she hoped to persuade NFL commissioner Bert Bell to help. Watching television in a hotel room, she saw a report about two towns some 80 miles to the northwest: Mauch (pronounced Mok) Chunk and East Mauch Chunk, from Native American words meaning "bear mountain." The towns, split by the Lehigh River, were locked in an intense rivalry. One was mostly German, the other Irish. "When they weren't getting along, one side would cut electricity to the other side because they had the transformer," says Danny McGinley, a local bartender and historian. "The other side had the water, so they would cut the water off over there." If a blaze broke out in one town, firefighters say, trucks from the other refused to help without special orders. Both towns depended upon railroads hauling coal, and both had boomed in the 1800s, attracting East Coast tycoons who built mansions and even an opera house. By the 1950s, coal was declining and the towns were economically depressed.

The TV report said Joe Boyle, editor of the Mauch Chunk Times News, was urging the towns to save money by combining. Boyle had established a fund to build infrastructure, lure employers and revive fortunes. He was asking all Chunkers to contribute a nickel each week. The Nickel a Week Fund caught Patsy's eye. She went to Mauch Chunk and sat down with Boyle. They cut a deal. Patsy would hand over Jim Thorpe's body if her dead husband was honored with a tomb and a public memorial. The towns would combine and rename themselves Jim Thorpe, Pa. The name, she said, would draw tourists and restore the economy.

Boyle died in 1992 and never revealed the terms of the arrangement. Neither have any other leaders among the Chunkers, many of whom are no longer living. Wheeler says Boyle told him that Patsy was paid, but only to reimburse the cost of her travel and lodging.

Not everyone in Jim Thorpe, Pa., was happy with the agreement. Joe Boyle's daughter, Rita, now living in Texas, says, "Daddy took a lot of heat for it because of the name change. My daddy's life was threatened."

Some residents started calling the town "Jim Chunk."

“It bothered him, the look of it, as if no one even really cared. The whole thing really hit him, how far away his father was from home.”

- Anita, on her father Richard's reaction to Jim's grave

Still, when the pact was put to a vote in May 1954, the Chunkers approved consolidation and the tomb by a landslide. The body of Jim Thorpe was sure to create a renaissance. Maybe the NFL would build its Hall of Fame in Jim Thorpe, Pa. Maybe developers would invest in accommodations for a huge influx of tourists, perhaps even a hospital. Maybe there would be an athletic field and a manufacturing plant for sporting goods -- all with good paying jobs. Patsy talked of constructing a hotel with a Native American theme: Jim Thorpe's Teepees.

While a memorial was constructed, Thorpe's body sat in a mausoleum in a local mortuary. At one point, a rumor surfaced that his body hadn't actually been inside the casket that Patsy delivered. Joe Boyle and a group of other residents opened the crypt. Onlookers saw that Thorpe was indeed inside, his head wrapped in a plastic bag.

In 1957, Thorpe's body was placed in the new tomb. Etched on the sides of the red stone monument were pictures of Jim Thorpe playing football and baseball and running track, along with the words spoken by King Gustav V of Sweden at the end of the Stockholm Games: "You, sir, are the greatest athlete in the world." Thorpe's children did not attend the dedication.

There would never be a hall of fame or a hospital, no Jim Thorpe's Teepees. To this day, people on the streets of Jim Thorpe, Pa., recite a remark by a city leader, in a Sports Illustrated story from 1982: "All we got here is a dead Indian."

The tomb and its surroundings fell into disrepair. In the 1990s, Richard Thorpe, along with his daughter, Anita, and her two children, visited the Pro Football Hall of Fame in Canton, Ohio. They drove farther on, to Jim Thorpe, Pa., where Anita recalls Richard's shock at seeing his father's memorial. Alongside the road, she said it looked like a place where people might stop to "relieve themselves." "Dad was talkative and cheerful the whole way. Then he saw it, and the moment he did, and from then on all the way back, he hardly said a word," she says. "It bothered him, the look of it, as if no one even really cared. The whole thing really hit him, how far away his father was from home."

Bill visited the roadside crypt in the 1960s. "I was saddened to my core," he says. "At that particular time, they didn't even have a sidewalk in front of his plaque. I was there by myself, and I just wanted to spend some time. I stayed for, I don't know, 30, 40, 50 minutes. I was upset. The place looked like -- you know, it looked like hell. The lawn wasn't mowed. Weeds were there, and everything else, you know.

"But I stayed around, and I visited [with Dad]. We talked."

His voice quivers, and tears appear behind his wire-rimmed glasses. "It was just, you know -- [I was] sorry to see him go. I can't remember what I said or anything like that, but it was -- it was emotional. Actually, we talked."

Bill says he got a feeling that his father "wasn't in the right place."

Jim wasn't an "easy" father. "I think I still have a few scars on my butt from when he took a belt to us," says Bill, on the right with his father in 1931. Sports Studio Photos/Getty Images

JIM THORPE'S OTHER children shared the feeling. At first they were united. All of them wanted their father's body returned. In time, however, his daughters came to accept Jim Thorpe, Pa. In 1998, Grace presided over a rededication of her father's tomb. "I want to thank the community for all that you've done," she said. "I know my dad is happy to rest here."

At one point, son Jack seemed to agree. He wrote a letter to the town saying, "I now feel that the remains of Jim Thorpe are in a good place, and he is at peace." But then he changed his mind and rejoined his brothers in demanding that their father be brought back to Oklahoma. The presence or absence of Jim Thorpe's bones, the sons said, would not make or break the town of Jim Thorpe, Pa.

On June 24, 2010, Jack Thorpe, who by now had served for several years as chief of the Sac and Fox tribe, mounted a legal attack. Patsy had died in 1975, so Jack sued the town.

His lawsuit, filed in Pennsylvania federal court, cited the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, passed by Congress in 1990, requiring the return of Native American remains and sacred objects. The law, known as NAGPRA, gives tribes and families a way to repatriate Indian remains from museums, which it defines as any agency or institution that receives federal funds.

Over the years, hundreds of thousands of native people have been dug from their graves for storage or display at museums, universities and an array of gallery exhibitions across the country. At a 1987 congressional hearing, Robert McCormick Adams, secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, testified that 42.5 percent of the 34,000 human remains in its collection were from Native Americans.

The federal government itself has exhumed Native Americans. In 1867, the Army surgeon general ordered military medical officers to send him Indian skeletons to study. The goal was to build research collections that aimed to prove white superiority by demonstrating that Indians had smaller craniums. The directive encouraged widespread looting. Medical officers, soldiers and sometimes civilians collected skulls from battlefields and waited for funerals to finish, then raided burial sites for skulls and bodies to send to Washington.

Using NAGPRA, the 4,000 members of the Sac and Fox tribe already had won the return of nearly 100 bodies. Suzan Shown Harjo, a Cheyenne and Muscogee who helped develop the act and get it passed, says bringing Jim Thorpe home would be important not just for the Sac and Fox but for all Native Americans. "It would send a message that our people are not being stepped on," she says. "It would show we are not going to be kept as collections or roadside attractions anymore. We are going to stand up to that."

THE SUIT ENRAGED the Thorpians, as residents had come to call themselves.

"The state of Oklahoma wanted nothing to do with Jim Thorpe, and a community took him in -- our community," says Michael Sofranko, the longtime mayor. "This is the place that took Jim Thorpe in. [We] changed the name of the community, and we have held up our end of the contract. We have done everything we were asked to do."

Six decades after the arrival of Thorpe's body, the fortunes of Jim Thorpe, Pa., have, indeed, picked up. Divisions have melted. The economy is strong for a town of only 5,000 in a region still being buffeted by the recent recession. Now, when Mayor Sofranko sits on the second-floor deck at the well-appointed Inn at Jim Thorpe, he sees Broadway bustling with people. Many are tourists. Some pedal red and yellow mountain bikes. Others amble along in stylish hiking boots, passing art studios and coffee shops.

The mayor concedes that few of the visitors have come to see Thorpe's tomb. They are there to play in the surrounding hills and on nearby rivers, which have become a hot spot for hikers, bikers and whitewater rafters. But Jim Thorpe's tomb and monument has played a part in this, Sofranko says. "To get things going." And residents are proud to possess Jim Thorpe's body. To suggest this might be worth reconsidering, if only on moral grounds, makes the Thorpians dig in. Oklahoma had its chance, says Ray Brader, sitting in the back of his gift shop on Broadway. Mention the spiritual claims of the Sac and Fox, and Brader grows indignant. "Jim Thorpe the Olympian was brought here, not Jim Thorpe the Native American." Thorpe smiles from posters and photos on streetlights and restaurant walls. His image is on T-shirts and coffee mugs. Students go to Jim Thorpe Area High School, home of the Olympians. "The movie about him with Burt Lancaster ['Jim Thorpe: All-American,' released in 1951], is required viewing when you grow up here," says Brandon Fogal, manager of a whitewater rafting business. "You see that film again and again. You can't escape hearing about him. It's hard to find people of any age who don't feel an attachment."

Each spring, Jim Thorpe, Pa., celebrates the birthday of its namesake. At his tomb, a local troupe of Native Americans dance, pray, chant and beat drums. Improvements are noticeable. The tomb is well kept and has additions: a bronze statue of Thorpe throwing a discus, another of him holding a football. Plaques describe his feats. A metal sculpture of a lightning bolt reminds visitors of his Native American name.

At a firehouse in a neighborhood called The Heights, volunteer firefighter Jay Miller and his colleagues are suspicious. Miller says Oklahoma didn't care about Jim Thorpe until his Olympic medals were restored in 1983. Other townspeople have heard a rumor that the tribe wants to put Thorpe's bones in a casino to boost business. They seem to see little irony in the fact that they have used his bones to build their own economy. Ninety-five percent of the residents of Jim Thorpe, Pa., are white. By count of the latest census, the percentage of Native Americans in town is nearly zero. But its residents do not accept the view that Jim Thorpe is a stranger. They say he belongs with them.

Bill (left) and Richard (right) hope they live long enough to see their father returned home. Danny Wilcox Frazier/VII for ESPN

IN COURT, the Thorpians fought back.

Their attorneys argued that the town was not a museum, even under the most expansive definition of the law. Moreover, they said NAGPRA was not meant to apply to "modern remains such as those of Jim Thorpe." His wife and the town had signed a contract. "He was merely laid to rest," one court document read, "in accordance with his faith."

The town's case was helped by the fact that Jim Thorpe had never made a will. In the oral tradition of Native Americans, there are few written wills. The town's response also was strengthened by a legal brief from John Thorpe, the 59-year-old son of Jim's daughter Charlotte. In 2005, John, a Lake Tahoe disc jockey, had abandoned his father's surname, Adler, so he could take his grandfather's name instead. "I am extremely proud of my heritage," he says. Nonetheless, he favored leaving his grandfather's body in Jim Thorpe, Pa. He filed his brief after attending a Native American sun dance in Bastrop, Texas, where he went to a sweat lodge. In the steam and the smoke from burning cedar, John says, a spiritual healer "told me that he had made contact with my grandfather, and these were his words: 'I am at peace, and I want no more pain created in my name.'"

As the court battle waged, Jack Thorpe died of cancer at age 73. Bill and Richard Thorpe and the Sac and Fox tribe joined the lawsuit in his place.

On April 19, 2013, Judge Richard Caputo of the U.S. District Court of the Middle District of Pennsylvania ruled in favor of Jim Thorpe's sons and the tribe. NAGPRA, Caputo said, superseded contract law. Congress, he said, had "recognized larger and different concerns in such circumstances, namely, the sanctity of the Native American culture's treatment of the remains of those of Native American ancestry."

Bill Thorpe remembers thinking: "This is all going to be done with soon. Justice."

NEARLY 300 ANGRY Thorpians packed a town hall. "We had an open discussion on what to do," Ray Brader says. "It was very emotional." Speakers included members of the Jim Thorpe High School history club. "It was beautiful," adds his co-worker, Anne Marie Fitzpatrick. "The last thing they said was: 'Please leave our namesake alone.'"

The town decided to appeal.

On Oct. 23, 2014, a three-judge panel of the U.S. Third Circuit Court of Appeals overturned Caputo and ruled in favor of the Thorpians. The reversal was based on what is known as the "absurdity doctrine," which judges can use when they think the results of a case have gone against congressional intent.

Chief Judge Theodore McKee said Thorpe's burial accommodated the wishes of his wife and was therefore lawful. In addition, McKee said, Jim Thorpe, Pa., did not meet NAGPRA's definition of a museum, even as broad as the definition was.

"We find that applying NAGPRA to Thorpe's burial in the borough is ... a clearly absurd result ... contrary to Congress's intent to protect Native American burial sites," McKee wrote. Therefore, Jim Thorpe, Pa., "is not subject to the statute's requirement that his remains be 'returned' to Thorpe's descendants."

In Pennsylvania, there was joy, mixed with relief.

In Oklahoma, misery. "It felt like this was the same old story, the same old raw deal that Indian people have always gotten," says attorney Stephen Ward, who represented Thorpe's sons and the tribe. "It felt like the courts just don't work well for Indian people."

Bill and Richard Thorpe appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court.

On Oct. 5, 2015, the court declined to hear the case without comment.

Bill Thorpe heard the news over the phone. He could barely speak. "It hurt bad," he says. "The worst part of it is that we felt like we were not being heard. Not even given a listen, a chance to tell our story. It's as if you don't count or exist. But then again, we've gotten used to this sort of thing. It's the Indian way, maybe. We've had to get used to it. Disappointment. Bitter disappointment."

THE BONES OF Jim Thorpe do not rest easy.

Bill and Richard Thorpe and the Sac and Fox tribe believe that Jim Thorpe, Pa., wouldn't be harmed by giving up their father's remains. "What difference could it possibly make?" Richard says. "The town can keep its name and everything else. Just give Dad back."

There has been talk, however vague, of suing in state courts, of a boycott, of getting help from a wealthy Oklahoma oilman, "someone like T. Boone Pickens," says Massey, the Sac and Fox historic preservation officer.

More concretely, Bill Thorpe has engaged Tom Rodgers, a Washington lobbyist who was a key whistleblower in the 2006 case against Jack Abramoff, the D.C. power broker sent to prison for defrauding Native American tribes. Rodgers, a member of the Blackfeet tribe in Montana, is working pro bono.

He plans to meet with the civic leaders of Jim Thorpe, Pa. "I am going to appeal to their sense of ethics and morality," he says. "You are displaying a man's remains and making money off of it. Jim Thorpe may be buried there, but that is not his home. I will remind them of history: how the white man took our land, our children, and then they came and took our spirits and our bones. Failing that, we will go another route."

Rodgers won't say on the record what that route might be.

Meanwhile, the burial land waits. Thorpe's daughters are interred near Cushing, Oklahoma, surrounded by gentle hills in every direction. His first wife is laid to rest there, too. Behind her is a gray, leaning stone topped by a rounded sculpture of a baby lamb. Buffeted by a century of hard weather, its inscription is so worn that only part of it can be read: "James, Son of Jim/May 1915" -- the toddler who died in his arms. Near Stroud, there is a plot in a circular memorial park for military veterans, across the highway from a small casino and a few dozen paces from the tribal headquarters, a police station and grounds used for sacred tribal gatherings. And there is a flat, rectangular cemetery near the North Canadian River and a school that Jim Thorpe attended before he went to Carlisle. It is easy to imagine him as a boy there, chasing horses in the distance, hunting rabbits and squirrels. In one corner, by a low fence, near a leafy tree, lies his father, Hiram.

Bill reflects on the possible sites and thinks of his own father, Jim Thorpe.

He curls his right hand into a fist.

"We are not giving up."