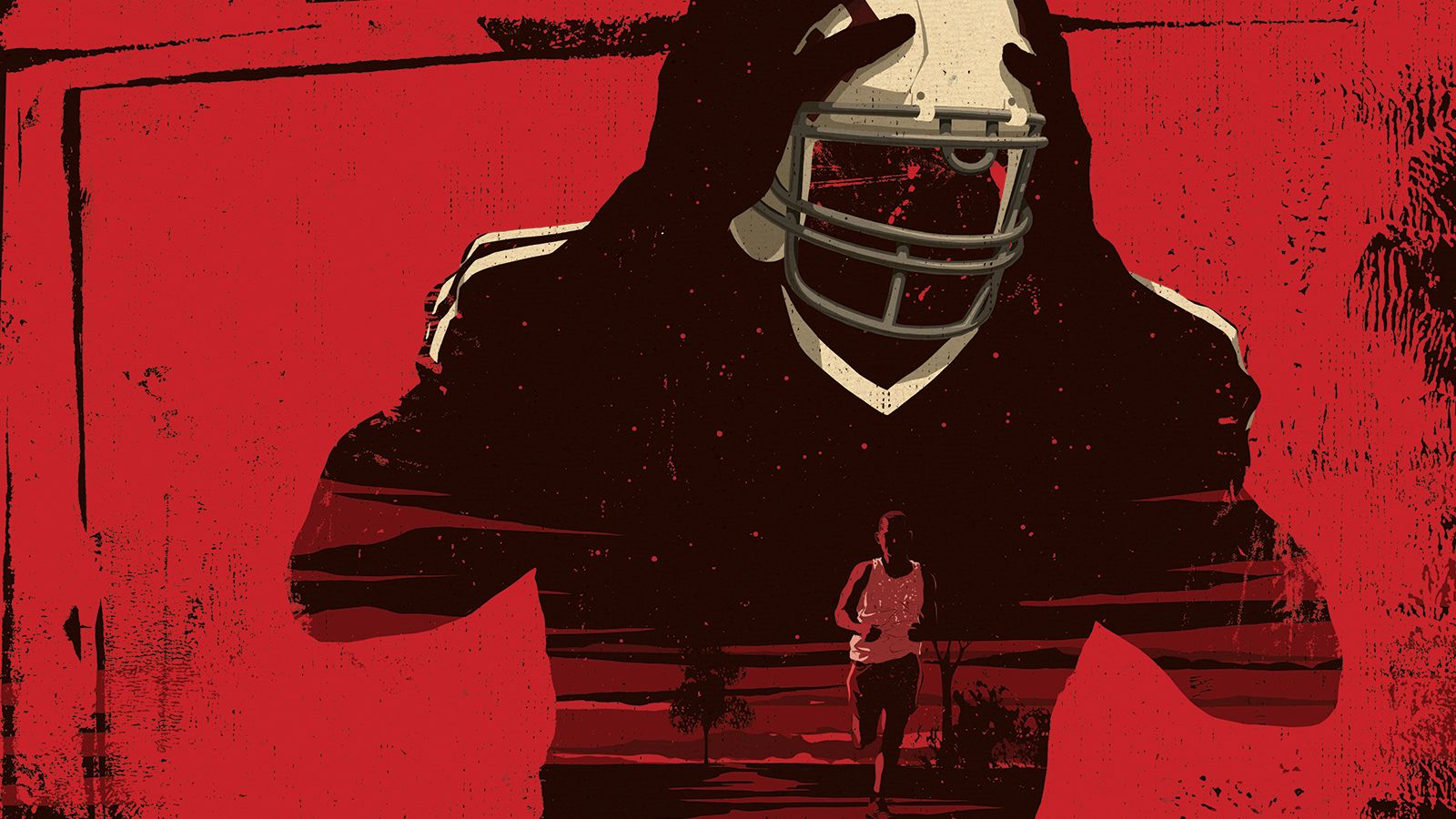

Broken Route

A former Texas A&M standout committed an unthinkable crime. How did so many people miss the warning signs?

Last Oct. 12, Dave Stevens slipped his sneakers on for a 90-minute run through the Dallas morning, a chance to clear his mind before heading to his job as an engineer. Every day he wrestled with small, knotty problems to solve larger ones, and most of his General Electric co-workers agreed that his designs were elegant in their simplicity, which was also a good way to describe Dave. He was quiet insofar as he chose his words carefully and had a spare, dry wit. But he also had a free-spirited streak and had recently begun looking at farmland in Oregon so he could raise livestock with his wife, Patti. It was his vision, at age 53, of an early retirement.

Dave also ran to train for the Dallas Marathon, just eight weeks away, aiming to beat his 3:27:03 time from a year earlier. Every so often he would take Patti, speeding ahead before turning back because he didn't like her running alone. But he was solo this morning, looking forward to gauging his pace.

Just before 7 a.m., Dave parked at the trail entrance in Valley View Park, threw his wallet into the glove compartment of his SUV and set off on his run. The sun was still half an hour from rising, but early birds getting in their Fitbit steps were already crowding the path. His favorite stretch of the course followed White Rock Creek through a collection of parks before emptying into a lake bordered by well-heeled homes. Once he passed Anderson Bonner Park, it would be a straight shot through Harry Moss Park until he got to West Lawther Drive and the mouth of the lake loop. There, he'd make his way around the wooden boardwalks with their picturesque views before starting on the return trip.

The temperature was perfect, still in the 70s, and as he started the course, he gulped in the fall air. About an hour later, he was two-thirds through his run and about to pass under the stone bridge that runs above Walnut Hill Lane when something caught his eye.

In 2012, Thomas Johnson was a standout freshman WR for Texas A&M. But he mysteriously left campus midseason, on his way to a fateful encounter three years later with a runner named Dave Stevens. Shaun Assael reports.John F. Rhodes / Special Contributor

THOMAS JOHNSON RAN to clear his mind too. As long as he could remember, his legs had taken him places. They carried him around the Dallas borough of Oak Cliff, past trouble on the corners and to sports and church programs. As his athletic talent became evident, he stepped up to bigger stages, like the Junior Olympics in Eugene, Oregon, where at age 9 he set a world record for his age group in the long jump. There was a lot about Thomas that made people want to be around him: the ease he had with himself, how he helped other kids and was unfailingly polite. The Friday night lights of suburban Dallas also revealed a young man whose mother had instilled in him a desire to see a broad world -- the kind a good education would bring. By 2012, he'd become the fourth-ranked football recruit in the state, and when he arrived at Texas A&M that fall, he emerged as one of Johnny Manziel's favorite targets. In just his 10th game, on the road at No. 1 Alabama, the true freshman made a trio of receptions that helped the Aggies past the defending national champion. When he got off the team bus in College Station that night to a raucous celebration, he looked every bit the future NFL star.

But Thomas Johnson never stepped onto a football field again. Instead, three years later, he was hurtling toward Dave Stevens by the stone bridge of Walnut Hill Lane.

AMERICA'S MENTALLY ILL are often overlooked or misunderstood. Interviews with Thomas Johnson's family members, court and police records, and doctors' diagnoses show that those closest to the college star were right beside him when he exhibited strange behaviors and acknowledged hearing voices, yet they all had difficulty interpreting the signs. Some were too ill-informed to understand what he needed, while others saw him through the lens of their own social conscience. Law enforcement officials mainly saw him as a typical drug abuser and figured there was nothing about him that a little rehab couldn't cure. His parents were too busy arguing with each other to agree on a diagnosis.

Three years after he heard his last stadium cheers, Thomas was unemployed, sleeping on friends' couches and, in the rare moments when he opened up, revealing a disturbing side that had already led to two arrests and several months in jail.

"You do know you're talking to yourself," his mother's sister said to him one day as she watched him carry on a one-way conversation. "I'm sorry," he replied, shaking his head with embarrassment.

Those close to Thomas weren't willing to confront the obvious: He was no longer only their problem.

From left: Thomas with his mom, Linda; with the Ehrhardts; and with Robert, three days before he crossed paths with Dave Stevens. Courtesy Linda Cradler; Courtesy Ehrhardt Family; Courtesy Robert Johnson

LINDA HANKS IS not quite 5 feet tall, with a soft, sometimes faint voice that understates the long-running battle she's waged with the world. Her mother died giving birth to her, and she grew up in Dallas with three sisters who helped her care for her twin brother, who died at 12 from fluid on the brain. She studied design at a two-year college, and after a brief marriage in the late 1980s, she had a fling with a truck driver named Robert Johnson, who lived in her apartment complex.

Linda, her faith in the Lord strong, proclaimed the two of them blessed when Thomas, their child, was born in April 1994. But the two never married. And as the years passed, Robert and Linda started hurting each other in the name of fighting over what was best for their son.

Linda raised Thomas with a single mother's single-mindedness. Her social services job at a hospital paid for a home in Oak Cliff with a large backyard that she filled with things like tire swings and trampolines, and her happiest memories came from watching Thomas practice the 100-yard dash in their backyard. She taught him to be respectful and not play into anyone's prejudices, and she kept a Bible at arm's reach to answer any questions he had. She made fashion bags at night to sell at work so she could afford the extra cost of track meets and travel games, and she used what she managed to save to take Thomas on trips -- Disney World one year, Washington, D.C., the next.

But to her irritation, Thomas' father, who'd had multiple convictions for theft, remained in the picture. In fact, Thomas lit up with joy whenever he arrived on their doorstep. But by 2005, the price of taking care of Thomas started to overwhelm Linda. She sought bankruptcy protection, citing just $1,753 a month in take-home pay and a lack of child support.

Thomas, a reserved 11-year-old, had already joined a travel football team in Arlington, half an hour away, and was being shuttled back and forth to practice by the team's owner, a wealthy businessman named Ted Ehrhardt. When Ted's son Mitchell learned about Thomas' financial troubles, he volunteered an idea: "Why doesn't Thomas just live with us?"

"It didn't happen overnight," Ehrhardt says. "He'd been visiting and hanging out with my son and spending every weekend with us for three years, doing the things that we do as family."

Ehrhardt, whose company installs and services fire alarm systems, paid for Thomas to attend Oakridge, a prestigious private school in Arlington, and took him on vacations to an island he owns in the Caribbean. A photo from the summer of 2008 shows Ted, a sometime sports agent, his wife, Stacey, and their three sons posing with Thomas on their private beach, all dressed in matching white shirts and khakis.

But as much as Linda wanted Thomas to see the world outside Oak Cliff, she winced when she opened a local magazine in April 2009, a year after he moved to Arlington, and read a profile about her son headlined "Most Grateful Player." The piece included a quote from Thomas, then a freshman, saying that before he met the Ehrhardts, "I was going to school in Dallas and getting into trouble."

Linda was stung by the suggestion that he was better off without her. And she became even more upset when Thomas' father married and moved to a home just 5 miles from the Ehrhardts. In December 2009, Linda drove to Arlington to tell the Ehrhardts she wanted her 15-year-old son back. "They're separating us," she said. "That's not the way it started out, you know?"

Thomas didn't show much emotion as his mother spoke. "It wasn't like he was bawling or crying," Ted recalls. "It was more like, 'My mom needs me. I need to go home with her.'"

Back in Oak Cliff, Linda rented her house so she could move Thomas closer to a magnet school, Skyline High, which has produced eight NFL players since 1994. But the arrangement didn't go as planned. Thomas announced that he wanted to start spending more time with his father and alternated between Robert's home in Arlington and the apartment of his father's sister near Skyline.

Skyline went 9-3 and 14-1 in his two seasons. But as Thomas became an Under Armour All-American wide receiver and Robert took an active role in managing his future, Linda felt more and more isolated from her son. "It was like the vultures were all over him," she says. "It just seemed like every person that came into Thomas' life was trying to control him and exclude me."

She also saw dark forces at work in the recruitment process.

"I know people say black magic don't exist," she says. "But [after Thomas committed] it's like he went to sleep and woke up a totally different kid."

After A&M's victory over Alabama, the Aggies' biggest win in more than a decade, Johnson abruptly left College Station. Mike Zarrilli/Getty Images

IN THE SUMMER of 2012, Thomas joined a hopeful Aggies team that was entering the SEC with a new coach, Kevin Sumlin, and weapons at almost every position. The only glaring vacancy was at quarterback, and Sumlin chose an obscure redshirt freshman, Manziel, to fill it.

A close friend of Linda's who'd died years earlier and had acted as a godfather to Thomas left him an inheritance for when he turned 18. He wasn't shy about spending it, buying a Chevy Malibu for himself and a Chrysler Sebring for his mother, gifts for friends and an engagement ring for a girl he was dating back home.

On the field, his quiet confidence meshed with Manziel's bravado. When the Aggies rolled into Tuscaloosa on Nov. 10, 2012, they were ranked 15th with a 7-2 record. Alabama was undefeated, but the Aggies scarcely needed three minutes to score their first touchdown. By the end of the first quarter, A&M was up 20-0 in a game it would hold on to win 29-24. Thomas caught only three passes, but each one helped keep a scoring drive alive.

Then, in the aftermath of the Aggies' biggest win in more than a decade, Thomas abruptly left College Station -- a departure that even now is blurred by questions. In the weeks before the game, Thomas had begun comparing himself to the character played by Denzel Washington in The Book of Eli, a post-apocalyptic film about a loner who hears a voice that tells him to deliver a sacred text to a secret location on the West Coast.

According to his roommate, linebacker Michael Richardson, "he was breaking it down to us, and we were like, 'What are you watching, bro?' It was like he [had watched] a completely different movie." By then, Richardson says, "something had spiritually messed him up. He'd sit in his room for hours, reading his Bible and smoking weed. He got distant from everybody. I told him he needed help."

In an interview, Robert Johnson says his son confessed that he'd started smoking synthetic marijuana, or K-2. "I said, 'You've got to be out of your mind,'" he recalls. Thomas' answer -- "Ah, Dad, it's all good" -- hardly encouraged him.

Two days after the Alabama game, the Aggies had a special-teams meeting scheduled at the Bright Football Complex. Because Thomas' Malibu had broken down, Richardson offered to give him a lift. "Nah, it's OK," he said. "I'll see you there." Instead, shortly after 1 p.m., Thomas walked out of their apartment with the television on and didn't come back. The engagement ring he'd bought for his girlfriend was in his pocket; he wanted to give it to her personally. His knapsack was full of Bibles.

There was a Greyhound station 30 miles away, in Hearne, and Thomas walked the entire way. His feet became so blistered that he took off his shoes to walk the final stretch barefoot. It wasn't until the next day, when he failed to show up to a second straight practice, that his coaches realized he was gone.

As Brian Polian, then the Aggies' special-teams coordinator, recalls: "We had law enforcement from different agencies trying to track him down, and no answers." Adds Richardson: "We had cops watching our house. They didn't know if someone had done something to Thomas, and honestly, neither did we."

According to a campus police report, Aggies wide receivers coach David Beaty told an officer that Thomas had "been very religious" in recent weeks. When the officer followed up with Linda, she confirmed that a change had come over her son. In fact, she said, she was concerned enough about the messages he was "getting from the Bible" that she'd brought him to a Dallas-area minister so that Thomas "could better understand" what he was reading.

Linda, however, never referred Thomas to a health professional. And there is no evidence that anyone in authority at A&M did either.

Sumlin and Beaty, now the head coach at Kansas, declined to speak with Outside the Lines. And A&M athletic department spokesman Alan Cannon cited federal student privacy restrictions when saying he "could not comment about a current or former student's medical care." Cannon did say, however, that football players, like all students, receive orientation materials that make them aware of resources on campus, including mental health counseling.

The statewide manhunt for Thomas came to an end three days after his departure, when Robert Johnson found him at the home of a high school friend, talking in a garage. The truck driver tried to coax his son out, but Thomas wouldn't budge. Seeing no other option, Robert called the police. When Thomas spotted a squad car pulling up, he bolted out a back door and started running. "Thomas is crazy," his friend told the officers. "He believes he's Jesus."

With a helicopter searching overhead, Thomas ran to a nearby park, where he frantically called his girlfriend. "I'm hungry, I'm cold. Will you just come see me?" he begged.

Frightened for Thomas' safety, his girlfriend informed detectives, who arranged to follow her as she drove to the park. When he got into her car shivering and disheveled, she drove straight into a prearranged traffic stop. Thomas was taken into custody without incident and transported to a psychiatric hospital, Green Oaks, for evaluation.

After three days of court-ordered supervision, Thomas left Green Oaks with his father. "I said, 'Son, I need you to tell me what's going on. If you don't tell me, I don't know how to help you,'" Robert recalls.

Thomas' reply, he says, was pleading: "Dad, I'm hearing these voices in my head. ... They're just telling me to do different things. Stuff I don't want to do."

A few days later, Robert brought his son to an outpatient facility where, he says, Thomas received a diagnosis of schizophrenia. But in a foreshadowing of his future, Thomas refused medication or long-term care. "He didn't want to go to a hospital because he was afraid he'd be treated like a nutcase," Robert says.

Unless someone petitioned the court to declare him incompetent -- a drastic step that no one was ready to take -- Thomas was free to chart his own course.

A white cross marks the spot of the attack on Stevens. Guy Reynolds/The Dallas Morning News

ELIJAH SMITH WANTED to be just like Thomas.

Six years younger than his second cousin, he had visions of becoming a football star and was thrilled that he got to drive with Thomas to College Station in the summer of 2012 to check out his new home.

But just six months later, soon after Thomas was released from Green Oaks, Elijah saw a different side of his cousin. "Please forgive me," Thomas said when he stopped by Elijah's house one evening. "I sold my soul to the devil."

Elijah told Thomas it was late and he needed to get some rest. But Thomas left, only to return past midnight to speak to Elijah's father, Roderick.

"We have to deliver Elijah," Roderick recalls him saying.

"Deliver him where?"

"To the crucifixion."

"No, you won't be delivering him tonight," Roderick said, stepping back. Thomas looked up to his second cousin's bedroom.

"Is Elijah up?"

"Elijah is not up," Roderick answered. "And I'm not gonna go wake him up."

"God don't sleep," Thomas replied.

The sound of the two men talking roused Elijah, who turned on the bathroom light.

"See," Thomas said. "I told you God don't sleep."

Later, Roderick told his son that he should stop hanging around Thomas. He also phoned his uncle Robert to say something was seriously wrong with Thomas.

What happened next is the subject of some debate. Robert says he arrived at the apartment that Thomas shared with his mother in the company of a doctor and social worker in the hopes he could coax Thomas to a hospital. But he says Linda blocked their way, insisting it was another attempt by him to separate her from her son.

Linda, for her part, denies that ever happened. Instead, she says, "they threw around schizophrenia. I don't know. I don't know much about it. ... I think it was something else going on that was mind-altering. In some form or fashion, his mind had been altered."

"If you don't tell me, I don't know how to help you," Robert said to his son. Lisa Krantz for ESPN

REMARKABLY, EVEN AFTER Thomas formally withdrew from A&M in December 2012, severing ties with the university and removing any potential for medical care on campus, his football career wasn't over. Terance Perine, a personal trainer and friend of the family, emailed coaches to see whether there was any interest in him and says he got a bite from TCU. But Thomas never called the school to follow up. "He never responded," Perine says.

Perine also tried junior colleges. But the results were the same. Finally, he gave up and arranged an interview for Thomas at McDonald's. That didn't go any better.

Robert also tried to find his son a job. He attempted to teach Thomas how to drive a truck, get him work in the oil fields. Each time, the answer came back, "No, Dad, that's not what I want to do." One day, Thomas expressed an interest in selling cars. "I went and bought him new clothes and got ready to take him to a friend of mine who sold cars," Robert says. "He said, 'No, that ain't what I said I want to do.'"

It was during this period that Thomas began to take walks that, family members say, lasted as long as a day. "I asked him why he walked so much and he said it was because he couldn't sleep," recalls Brenda Cradler, his mother's sister. "He said the voices in his head wouldn't stop."

On April 8, 2014 -- three days after the Aggies finished their spring practice and 16 months after he left A&M -- Thomas decided to return to College Station. But his car was broken down and couldn't make the trip, so he went to a place where he knew he could find a substitute: the day care center that his mother's other sister, Clarissa Pitts, ran in her home.

Thomas waited until he saw his aunt leave in the afternoon, then broke a window and grabbed the keys to her Chevy van. After about 90 minutes, he drove off to College Station.

When Clarissa returned that night to see her home burglarized, she called the police and handed over a security video. It showed her nephew pacing around with a kitchen knife, looking nervously out the windows every few minutes.

Clarissa wasn't the only one unnerved by Thomas' behavior that day. Richardson, his former roommate, recalls that Coach Beaty called him in a panic when Thomas showed up at the Bright Football Complex and was walking in circles and talking to himself. "He said [Thomas] came down with a backpack and looked bad and was trying to get on the team," Richardson says. Beaty offered to get Thomas help. "But TJ didn't want to hear that," Richardson says. "Coach Beaty had to get him escorted out because he was getting aggressive."

On the way back home the next afternoon, Thomas was arrested outside Waco by a cop who'd been alerted to the stolen van and who transported him to Dallas County Jail. Many of those closest to Thomas hoped he'd finally hit bottom, that he'd finally get the help he needed. But little changed. Instead, he spent three months in the jail before another Samaritan stepped into the picture -- Dave Stephenson, a sports marketing executive who was close to Thomas' old coaches at Skyline.

In July 2014, Stephenson bailed Thomas out of jail and brought him to a care pastor he knew in Dallas for a counseling session. After 90 minutes with Thomas, Stephenson recalls, the pastor "told us that he was very complex, that there were a lot of issues with his mother and father that he hadn't resolved."

The two developed something they called the Jeremiah 29:11 Plan, which involved a mix of Bible study, work on the farm where Stephenson lives, drug testing and sessions with a psychologist. They also persuaded Clarissa to drop the stolen-car charge if Thomas completed the program.

And so it was that Thomas found himself residing on a 4-acre expanse 50 miles outside Dallas, in yet another place that was supposed to offer him sanctuary. He woke up to Bible study each morning, ate a full breakfast, then drove to a nearby gym for a workout before returning for counseling with Stephenson and his wife, Lisa. The couple also hired a consultant to help make sure Thomas would be NCAA-eligible, hoping to pick up where Perine left off.

But early in August 2014, on the very day that Thomas was scheduled to have his first session with a psychologist, he announced he'd spoken with his mother and was leaving their farm without making the visit. Stephenson tried to talk Thomas into staying. Not only would leaving violate the terms of his diversion program, Stephenson said, but Thomas would be putting himself into the same environment that had seemed to stoke his erratic behavior. "We didn't know what to do," Stephenson says.

Eventually, the couple agreed to drive Thomas to an overnight visit with Linda. The next day, though, when he called Linda to arrange to pick him up, she told him Thomas had left and she didn't know where he'd gone. "We never heard from Linda again," says Stephenson, who immediately notified Thomas' probation officer. "She didn't take our calls."

“I know people say black magic don't exist. But [after Thomas committed to Texas A&M] it's like he went to sleep and woke up a totally different kid.”

- Linda Hanks

A WEEK AFTER he was reunited with Linda, Thomas walked to his aunt Clarissa's home in Duncanville, about 20 miles away, with the intent of apologizing for taking her van. But his hair was dirty and matted, his eyes were darting, and his disheveled look convinced his aunt that he was a danger to her kids. She huddled them inside her home, locked the doors and called the police.

Thomas was on his aunt's porch when two police cruisers pulled up. "Why are you here?" he asked one of the cops who got out. When the officer replied that he was responding to a report of suspicious activity, Thomas said, "I didn't call anyone," and he started walking off. The officer blocked his path, but Thomas ignored him and broke into a full sprint. He was captured a few blocks away and booked on a misdemeanor charge of evading arrest.

Over the next year, Thomas went into a complete free fall. He tested positive for marijuana, missed an appointment with his probation officer, failed to pay $640 in court costs and neglected to enroll in a safe-neighborhoods program. But when he appeared before a Dallas County magistrate on the evasion charge in January 2015, he was treated like just a drug addict with a low-level rap sheet. The judge suspended a 45-day jail sentence in favor of having Thomas complete a six-month stay in a drug rehabilitation center.

"Everyone just assumed he had a drug problem," Brenda Cradler says. "But it wasn't drugs. It was not that at all."

(A representative for the Dallas County district attorney declined to comment for this story.)

When Thomas was finally released in July 2015, the anger he had previously shown in flashes was residing much closer to the surface. He also began to tell a story about why he had left Texas A&M three years earlier.

In separate interviews with Outside the Lines, five people -- Thomas' mother and father, his aunt Brenda and two others who know him well -- recalled him using similar language to describe an episode that he said traumatized him at a team celebration after he'd returned from the Alabama game in November 2012.

"He told me he'd been raped," Linda says. "And he was really angry. Believe me, he was really angry."

The Texas A&M police report into Thomas' 2012 disappearance does not mention anything about a sex crime. Polian says he never heard talk of an investigation in any meeting. And Cannon, the football department spokesman, says no incident ever came to his attention. Richardson says Thomas was in fine spirits when he went out with the team that night. "He usually stayed in that house, so it was a big deal that he came out with us," the ex-roommate recalls. "We all tried to have a good time. And we did."

Whatever happened that night, "he couldn't handle it," his aunt Brenda says. "He could not handle it. He could not handle it."

LINDA HANKS SPENT the evening of Oct. 10, 2015, with Thomas watching War Room, a film celebrated for its message about prayer. She says she felt the way she used to feel -- like her son was still the center of her world.

Linda had spent every last bit of her praying power on Thomas. She prayed beside him, prayed at church, prayed alone and now she was praying as they watched the movie about prayer.

Thomas was in a good mood as he watched the movie and giggled through the funny parts, like he did when they used to watch The Three Stooges together. When the film ended at 9:30 p.m., he got up and announced he was going out. He didn't say where, and Linda didn't ask.

When she awoke on Sunday morning and saw that her son hadn't returned, Linda showered, dressed for church and was about to leave when she heard a key turn in her front door. Linda recalls that Thomas stormed inside "in the anger zone."

"He was looking for something -- I don't know what," she says. "When I asked him, he started calling me all outta my name," meaning he cursed at her.

"You can't stay with me calling me outta my name," Linda remembers saying. "I love you. And I've stood by you. But I can't take that." As she puts it, "It wasn't like I said, 'Get out.' I said, 'You can't be that way to me and live here with me.'"

But the effect on Thomas was the same. He stormed out of the house with a long-bladed knife, hurling insults at Linda as he left.

"I don't think she wanted to push him away," her sister Brenda says. "Sometimes we find these safe spots and say, 'Well, you know, it may not go away, but I can control it.' ... I believe she was trying to protect him. I believe her love was strong. But she smothered him. I mean, what do you do with that?"

Linda decided not to go to church that morning. Instead, she took her Bible into a small closet that she uses for prayer, closed the door and fell to her knees.

Stevens ran the Dallas Marathon in 2014 and was training for 2015 on a trail by White Rock Lake. SPORT PHOTO, AP Photo

AT 7:32 ON Monday, Oct. 12, the sun had just risen over the Walnut Hill Lane Bridge when a pedestrian called 911 to report "a huge crazed man in the park." The witness was scared enough to take out a can of pepper spray and later remarked: "The best way to describe it is his brain was clearly in another atmosphere. I knew this guy was trouble, a scary stare."

Twenty minutes after the police dispatcher was given a description of a man wearing a gray hoodie, Dave Stevens was in full stride on the final leg of his run. As he approached the bridge, he most likely had only a few seconds to process the man with the scary stare and the machete who was lunging at him.

A cyclist phoned 911 to report what he thought at first glance was a man chopping wood. But before police could respond to that call, Thomas was already walking down the path and asking a passerby to borrow a cellphone. After calmly dialing 911, he told the dispatcher, "There's a man laying down with a sword in his head and not moving."

Then he walked back to Dave Stevens and waited. When the police arrived, he told an officer, "I just committed capital murder."

PATTI STEVENS SPENT a day furiously calling police stations before she got word that her husband, who was without identification when he was found, was the victim in the White Rock murder. A week later, as neighbors criticized the Dallas PD's slow response to the initial 911 call, Patti was still trying to make sense of it all when she sat down with a reporter for The Dallas Morning News, Naomi Martin.

Martin opened with a question about what Patti liked most about Dave when they first met, but Patti, to her own surprise, seemed unprepared to dial her memory that far back. "Oh gosh, oh my gosh. He was just such a quiet, polite ..." She stammered. "Oh, I should have thought about that."

Dave's parents, who'd flown in from Michigan, jumped in to help. "He liked competition, especially from himself," said Harry Stevens, a retired college professor. "He really liked to see his [marathon] numbers get better. He had that inner competition."

Slowly finding her voice, Patti picked up the thread. "He was always a gentleman," she said. "Whenever I'd walk through a door, Dave would hold it open for me. ... A perfectionist at home too. Very thorough." Turning to the home that they'd built in the Dallas suburb of Sunnyvale, she added: "My sweet husband let me basically have everything I wanted."

With the interview drawing to a close, Martin asked Patti, "What do you see being next from here?" But the weight of looking forward seemed to be too much. Through tears, she replied: "I'll just say, Dave was the love of my life. And I'm lost without him."

Six days later, a Saturday, Patti gathered some photos of herself and Dave and arrayed them on her kitchen table. Next, she scribbled a few personal details on a note for Martin, in case The Dallas Morning News wanted to write about her again.

Finally, Patti walked into her garage, closed the door and turned on her SUV. Lying on the floor beside the vehicle, she waited for the carbon monoxide to take her away.

CURRENTLY, THOMAS JOHNSON is lodged at Dallas County Jail, where he's refusing to see visitors, including his parents and his attorney. A court-appointed psychiatrist has found him incompetent to stand trial on an indictment that charges him with "intentionally and knowingly caus[ing] the death of Dave Stevens by inflicting chop wounds to deceased with a machete." He is awaiting transfer to a state psychiatric facility, where he'll stay until a judge rules he's fit to stand trial.

One of the few times his father has been able to see him came hours after his arrest. Thomas was still in his street clothes in the jail, and the two faced each other through thick glass.

"Are you OK?" Robert asked through a telephone.

"I'm good," Thomas replied. "I killed a man, Dad."

Robert stared into his son's eyes.

"So you're not all right?" Robert said, a crack in his voice.

"No, Dad," Thomas replied. "I'm good."

Additional reporting by Caitlin Stanco and Mike Ehrlich of Outside the Lines.