Mad Money

When Tyler Johnson signed a $50 million deal, the world lost its mind. Here's the crazy thing: He might be worth it.

On July 2, not 48 hours into the financial chaos of free agency, the newest face of basketball opulence stood over a hotel toilet and barfed.

Tyler Johnson had been told for weeks that this would be the most lucrative offseason for a semi-anonymous backup combo guard in NBA history. His agents said so. His superstar teammate on the Heat, Chris Bosh, said so. But now, on Day 2 of free agency, the numbers Johnson had heard -- 8 million per year ... no, 9 million ... no, wait, 10 million -- somehow looked conservative.

Serious multiperson delegations from the Rockets, Kings and Nets had all come to downtown Chicago, where Johnson's agents are based, to meet the 24-year-old. The fact that he'd averaged only 7.4 points for Miami over 68 career games -- less than one full season -- deterred none of the general managers or coaches paying homage. "I kept feeling like someone was going to be like, 'Psych! Just kidding! None of this is real!' " Johnson says.

To pry him away from Miami, which had the right to match any contract, the Nets phoned Johnson's agents with a ballooning, back-loaded offer -- one that caused him to lie, facedown, on the carpet of their office.

And then flee, minutes later, for the safety of his hotel room across the street. And then call his mother, Jennifer, back home in Mountain View, California, to cryptically exhale, "We did it." And then vomit -- not once but twice -- as the sheer thought of a four-year, $50 million contract caused Tyler's body to revolt against his brain.

"S---," Bosh said after hearing the news. "Fifty?"

"We hadn't even come to a decision yet," Johnson recalls of the ongoing bidding war, "but I didn't know how to react."

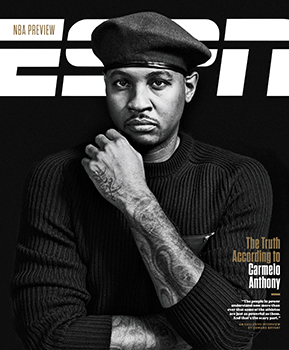

Michael Jordan made $94 million in salary over his 15-year career. Johnson made more than half that in a single contract. Steve Mitchell-USA TODAY Sports

ON THE OFF chance that you'd heard of Tyler Johnson before encountering this story, it was likely thanks to the following sentiment: These guys are ridiculously overpaid.

Which is understandable. As any self-respecting NBA nerd can tell you, the salary cap abruptly surged from $70 million last season to $94 million this season, the scheduled result of a nine-year, $24 billion broadcast rights deal the league signed with Turner and ESPN in 2014. And so it was, in July, that front offices earmarked roughly $3 billion guaranteed for players over the first 96 hours of free agency alone.

"Call me a hater," Steelers running back DeAngelo Williams said on Twitter, echoing his NFL colleagues, "but these NBA deals are insane." Now making it rain? The obscure, questionable likes of Timofey Mozgov (four years, $64 million from the Lakers), Evan Turner (four years, $70 million from the Trail Blazers), Solomon Hill (four years, $48 million from the Pelicans), Kent Bazemore (four years, $70 million from the Hawks) and on and on. Michael Jordan, it was pointed out, made a comparatively modest $94 million in salary over his 15-year career. An organism like Tyler Johnson making more than half of Jordan's earnings in a single contract seemed epically undeserved.

HoopsHype.com declared Johnson one of the three worst signings of free agency 2016. USA Today wrote, "I know he's shown flashes, but that seems like way too much money to invest in his potential." Johnson, who shoots a respectable 38 percent from 3, could not help but sarcastically hit "like" on this tweet: "You want 10mil just to miss wide open shots and lose teeth every time someone runs into you. Be gone white boy." Four days after that, he encountered a poll tweeted by a Miami fan account that asked, "Should the Heat match the Nets' offer for Tyler Johnson?"

Of the 995 respondents, 73 percent said no.

"People were like, 'Who is this guy? I have to look his name up on Google,' " Johnson says now. "They don't look at me and see $50 million, necessarily."

It's early August, and the 6-foot-4, 185-pound Johnson is wearing slides, shorts and a T-shirt in the lobby bar of the Fontainebleau Miami Beach. Unlike the conspicuously built Mozgov, or Turner, or Bazemore, or Hill, the pale, high-flying Johnson isn't obviously an NBA player. Not even to NBA players. After he swatted an Andre Miller finger roll during the 2014-15 season, Miller confessed, in genuine bewilderment, "I definitely didn't think you had that." And Johnson notes that when he grows out his closely cropped brown hair, his identity is even more masked -- as evidenced, in part, by the increase in strangers who call him white boy. (Tyler's father, Milton, is black.)

As for that tooth insult: Johnson is missing one of his lower incisors, the victim of a summer league collision last year. "I'm just letting it rock right now," he explains with a wide, gap-toothed grin. "I got my girl. I'm engaged. I'm in no rush."

Except when he is. Everybody who knows Johnson notes that he vibrates with a certain restlessness. "I'm sure he lost weight during the process of this thing," his mother says. "He wasn't able to eat well, not even when we were waiting the few days to see if the Heat were gonna keep him."

By that point, Tyler's teammates had already waved farewell on Twitter. Johnson had already started bookmarking Brooklyn real estate on Zillow.com. Ashley, his fiancée, had even gone online and shipped a box of Nets-branded shirts and pants for their 2-year-old son, Dameon, to their Miami condo.

Yet on July 10, the Heat vowed to back up the truck for a player they'd cut in the 2014 preseason and sent to the D-League's Sioux Falls Skyforce. Billionaire owner Micky Arison, who'd just let 34-year-old Dwyane Wade sign with Chicago, wanted to save Johnson. And while the Fresno State grad now cost a reasonable $5.6 million in Year 1 and $5.9 million in Year 2, those devious Nets had driven his price up to $18.9 million in Year 3 and $19.6 million in Year 4.

All of which is to say that Johnson and his obscure, questionable NBA cohorts -- Mozgov, Turner, Bazemore, Hill et al. -- are absolutely overpaid, yes.

But there's a lot more to why the NBA overpaid free agents in the summer. And there's more to Johnson's story than the fact that he fell into a crazy sum of money.

WHENEVER HER FIVE children were moved to tears, Master Sgt. Jennifer Johnson repeated a slogan: Get a straw and suck it up. "Meaning: Don't be a crybaby," the single mom and 31-year Air Force veteran recalls now. "Figure out what you gotta do."

"She'd say it for everything," Tyler says. "It's the most annoying saying ever."

“Call me a hater, but these NBA deals are insane.”

- DeAngelo Williams, Steelers RB

Whenever Jennifer, an airfield manager, suddenly had to deploy to Bosnia or Turkey or Djibouti or Qatar, often for months at a time? Tyler got a straw. (Each of the Johnson kids crashed with the family of a classmate.) Whenever money ran low, forcing everyone in the family to pinch pennies? Tyler got a straw. (One month, just before he entered third grade, the Johnsons even moved into a tent on a campground.) Whenever financial aid at Mountain View powerhouse St. Francis High required work during the semester? Tyler got a straw. (Sometimes literally: He served lunch to his classmates.)

Because of his mom's profession, Johnson had attended five different schools by the sixth grade. Milton, the man whose athleticism Tyler says he inherited, had left by the time his son got to high school. But Tyler's mission -- as declared in drawings, poems and unrelated homework assignments -- never changed. "He'd always tell me, 'I'm going to the NBA,' " Jennifer says. "And I'm going to take you with me."

It's impossible to miss how her straw slogan shaped Tyler's game. In seventh grade, he played with a right arm he didn't know was fractured. As a 5-8, 140-pound sophomore at St. Francis, he failed to make varsity, but he didn't relent. As a senior, when he received zero interest from major college programs, he played in a tournament on a torn meniscus. To this day, Johnson's coaches from Fresno State rave about the time he shattered two (other) teeth diving for a loose ball in a drill ... then picked up the scattered shards of enamel ... and kept practicing.

Such restlessness translated into a souped-up version of what scouts euphemistically call motor. "Sometimes Tyler will bristle when I tell him, 'Hey, you've got grit,'" Heat coach Erik Spoelstra says. "He may take that as, 'You don't have talent.' But his toughness is absolutely talent."

Last summer, for instance, he had two metal plates inserted into his jaw after he sprinted into Magic forward Branden Dawson during summer league. ("Good screen," Johnson recalls.) And this past February, at long last, the left-hander underwent surgery to address a soreness in his left shoulder that he'd first ignored as a college senior. Not until Johnson's rotator cuff gave out against Brooklyn in January -- he airballed a floater -- did he finally let up.

By March, weeks into recovery, Spoelstra had to summon Johnson into his quarters at AmericanAirlines Arena. When healthy, the guard had always insisted on doing an extra regimen of pre-practice workouts and post-practice drills. Spoelstra just wanted to ensure that Johnson, in rehab, was following doctor's orders and not rushing back for the playoffs that spring. "No, no, no, don't worry about me," Johnson assured.

"So who's this?" Spoelstra replied, before hitting play on an office monitor. Arena security footage, taken shortly before midnight, unmistakably showed Johnson sneaking in to do drills on the court. The punishment: $500 for an "unsupervised workout without clearance from a team physician" -- an infraction, Spoelstra admits, that he had to invent on the spot.

"Slow the f--- down," Bosh recently told Johnson. "Chill out. You only have one speed. You go from fast to fast."

Bosh signed a four-year, $114 million max contract in 2014. "I don't like to say, 'If this was an open market, I would've been making more,'" he says. "I'm happy for those guys." Photo by Joe Robbins/Getty Images

IN THE NBA, the question of who deserves what actually has an answer. An arcane 153,133-word answer. The league's collective bargaining agreement, last renegotiated in 2011, exists as part Magna Carta, establishing peace between owners and players, and part tax code, detailing the rules of finance. Its 551 pages constitute the most important document in basketball. And as the hysterics around free agency 2016 proved, an overwhelming majority of us couldn't care less.

If we did? It would be clear that, by rule, half of the record $24 billion in rights fees flooding the NBA marketplace has to be spent on players. It would be clear that every billionaire owner is required to pay his roster at least 90 percent of the salary cap every season, creating a salary floor that spiked from $63 million last year to $85 million this year. And it would be clear that righteous condemnation of Johnson and his cohorts might not make a ton of sense.

The timing of Johnson's expiring contract was essential to his windfall, admittedly. But in a market, timing is always everything. "Just look at the available shooting guards this summer," says Austin Brown, one of Johnson's agents. The top options under age 34 -- DeMar DeRozan, Bradley Beal, Jordan Clarkson, Nicolas Batum and Evan Fournier -- all immediately re-upped with their original teams on July 1. From there, it was no accident that Brook Lopez, the Nets' star center, flew out with team officials to woo Johnson. Or that Rockets coach Mike D'Antoni wined and dined him. Heck, Vlade Divac and Peja Stojakovic, two Kings stars-turned-executives, both showed up and topped Brooklyn's offer. Even then, famously cutthroat Heat president Pat Riley matched every single penny.

No one was fooled into giving away $50 million. Exactly the opposite: A rational market deemed Johnson worth exactly that.

But when it comes to player paychecks, many fans see these startling fortunes from the perspective of management: as costs to keep down. This is partly because of America's surging fetish for front office executives; thanks to some combination of fantasy sports and Moneyball, we are no longer a nation of aspiring athletes but vicarious bargain hunters.

But mostly, we empathize with ownership because it's sports. Fans have always been conditioned to root for teams -- proxies for our hometowns and our childhoods -- over the individuals who actually star in the games we cherish. A billionaire owner gets to embody the organization, gladly taking tax breaks and public money. A millionaire player, meanwhile, is more dangerous than any other type of entertainer. "An actor's not leaving your hometown to go somewhere else," Johnson says. An athlete threatens to betray you and those you love.

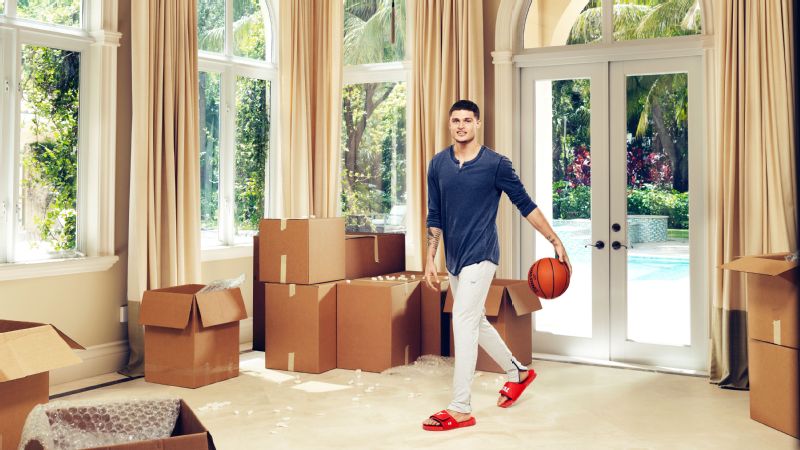

Cody Pickens for ESPN

FOR ALL THIS talk of capitalism and market value, however, even Tyler Johnson must concede that Tyler Johnson is overpaid. That's because the NBA's brand of capitalism, as detailed in the CBA, requires an asterisk. It is not quite capitalism. And the NBA's free market, as rational as it might be, is not quite free.

Understand: The salary cap has regulated payroll -- and, in ownership's view, enriched competitive balance -- since 1994. But just as critical, in tandem, are the cap's two cousins: the rookie wage scale, which has limited the earnings of the league's youngest players since 1995, and the maximum contract, which has done the same for the league's superstars since 1999.

Within those 551 pages of rules, it is decreed that no player can earn more than 35 percent of the salary cap -- and that he needs 10 years of experience to qualify for that maximum share. Six or fewer years limits a player to 25 percent of the cap, max; seven to nine years, 30 percent. "I don't know of any space other than the world of sports where there's this notion that we will artificially deflate what someone's able to make, just because," Michele Roberts, the executive director of the NBA players' association, told ESPN in 2014, months after she was hired. "It's incredibly un-American. My DNA is offended by it."

But Johnson -- like most of the NBA's 440-some-odd players -- is not offended. At all. He is refreshingly upfront about the reality that he benefits from the economic squeezing of rookies and stars. "I have no complaints," Johnson says. "It worked out in my favor." Players such as Johnson are overpaid because they, like owners, wish to profit from the rules too.

It's basic math. Without the max contract, league sources say, LeBron James would warrant significantly more than his $31 million annual salary, drying up the well for the lesser players on the roster. Instead, in the world of capped spending, James prompts us to consider an unsympathetic riddle: How can the NBA's highest-paid player still qualify as crazily underpaid?

No, not every superstar has agita over the boost given to the rank and file, and no one pretends to worry about a max player making ends meet. "I don't like to say, 'If this was an open market, I would've been making more,' " says Bosh, who signed a four-year, $114 million max contract in 2014. "I'm happy for those guys."

But with the CBA up for renegotiation in December, a curious political dynamic has a chance to shift. Roberts, for one, has basically condemned the max contract as unpatriotic. And the union, after being led by three consecutive role players (Michael Curry, Antonio Davis and Derek Fisher), is now under the direction of two max superstars -- placing them right across the table from commissioner Adam Silver.

Meet union president Chris Paul and his first vice president, LeBron James. Although they've remained publicly silent on this issue, both of them know what they could be worth. And for reasons of principle and self-interest, both of them could push for the abolition of the max contract.

"I kept feeling like someone was going to be like, 'Psych! Just kidding! None of this is real!'" Cody Pickens for ESPN

IT'S LATE AUGUST now, and Johnson is sitting with Ashley and Dameon in their rented two-bedroom on the 29th floor of a condo tower in Miami. In front of a modestly sized RCA flat-screen in the living room sits an infant's play mat. Packed plastic bins -- one hiding the Nets gear Ashley ordered -- line the blue-gray walls. At around 1,000 square feet, it's delightful for two young parents.

It is also one-twelfth the size of the roughly $5 million Mediterranean-style mansion Tyler just bought in Pinecrest, where they'll be moving in a few weeks. "I can't wait to get there," he says, scrolling through the Zillow listing on his iPhone. "It's got, like, crown moldings on all the ceilings. Which I guess is a big thing."

His biggest offseason concern remains rehab: slowing down, under medical advisement, in an attempt to fully heal his left shoulder. It first got sore at Fresno, he says, "because I was shooting an unnecessary amount." He'd walk into the gym and fire until, in his words, his technique "felt right." The routine was so familiar that a pregnant Ashley would come to the gym with her laptop and write papers on the sideline.

But now, Tyler knows, his obsession "was part of the problem." There are some issues that cannot be solved by getting a straw. "These days," he says, "I pay a little more attention to how I'm actually feeling."

It is not a courtesy he wishes to extend to his critics. Johnson wisely presumes that behind closed doors, there is envy around the league. But he has also resolved that he will not bend over backward to explain to anybody, anywhere, why Miami gave him a raise of more than 2,000 percent. "I won't bother explaining the salary cap, that the game is different now than it was before," Johnson says. "It's hard to break all that stuff down."

Besides: He didn't get into this business -- sacrificing shoulders, teeth, arms, legs and jaws -- for crown moldings. That is not why he remains so restless.

"My goal in the NBA wasn't to make a bunch of money," Johnson says. "When it's all said and done? I just want people to say, 'Man, that kid could play.' "