Lost And Found In Russia

Unlikely comrades Diana Taurasi and Brittney Griner play overseas for the money. As it turns out, they also simplify their lives.

This story appears in the WNBA20-themed issue of ESPN The Magazine, on sale May 13.

You absolutely must taste the pizza in the food court!" is not something you generally overhear in the U.S. But in Russia, good restaurants are in shopping malls.

The Ukrainian place on the second floor of this particular fluorescent box and the Italian place on the third floor are two of the best spots in Yekaterinburg, more than 1,000 miles east of Moscow. Shopping malls are heated, and numerous errands can be run in one place, which becomes irresistibly convenient when it's around 8 degrees with a windchill of minus 6, as it is tonight, was yesterday and will be tomorrow.

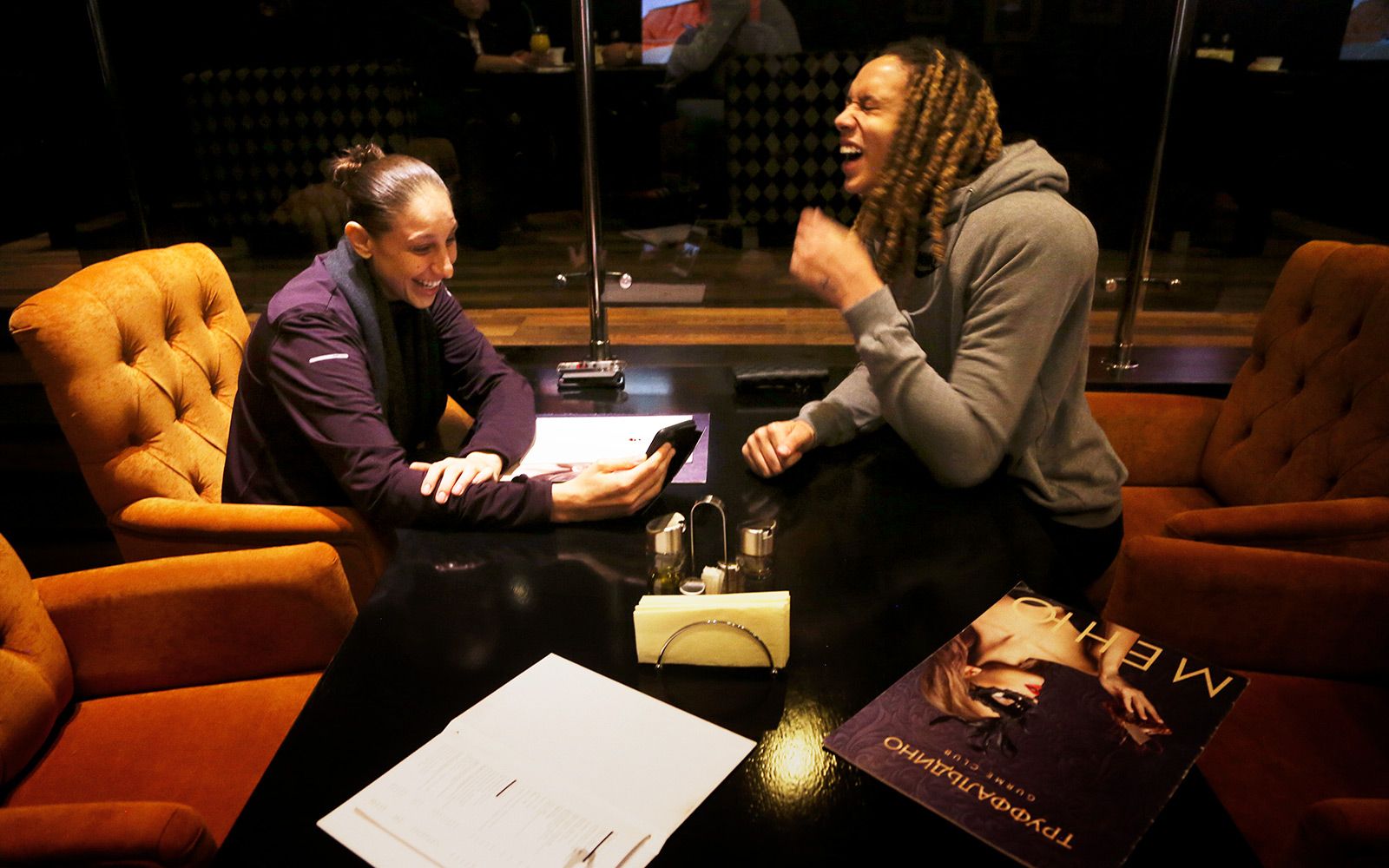

On this January day, Diana Taurasi and Brittney Griner walk to the mall from their apartment complex around the corner, then ride the escalator to the third floor. Taurasi is wearing a brimmed knit hat and gray wool Nike sweats, Griner a long-sleeved Nike camouflage shirt and matching beanie. As they stroll into the Italian restaurant, called Truffaldino, both check their coats, which in Russia is not optional, lest any public space become layered in fur and wool.

That both players actually walked to dinner is unusual. The club they play for, UMMC Yekaterinburg, provides each player with a personal driver, ensuring that they always arrive on time and also allowing them to say, without irony, "I'll have my driver pick you up."

So yes, Griner loves it in Russia. So does Taurasi.

And what's not to love? The restaurants are good, the team pays well and takes care of every detail -- chartering flights to away games, delivering bottled water to their apartments -- the arena is always filled with locals, and the coaching staff is essentially Phoenix Mercury (Far) East. Sandy Brondello, the Mercury's head coach, is an assistant for UMMC, and her husband and former WNBA associate head coach, Olaf Lange, is UMMC's head coach. Plus, a third of the team is American, playing on foreign passports, and those who are not speak English.

Still, that's just the exoskeleton of why Griner, in particular, is thriving here. The core reason is actually more complicated: She's checked herself out of the daily news cycle and checked herself into a crash course on maturity -- taught by Taurasi.

"I don't have to talk to anybody over here," Griner says. "I don't have to see anybody. I don't have to answer my phone. And everybody is asleep half the time when I'm up. I can be disconnected when I'm over here."

Griner, 25, left the States last October with her private life in public shambles, including a joint domestic violence arrest with then-fiancée Glory Johnson in April 2015, an ill-advised wedding two weeks later, an annulment filing plastered all over TMZ just a month after that, a seven-game suspension from the WNBA for her role in the mutual altercation, then media accounts of the former couple's disputes, as well as public court rulings over alimony and child support. (Johnson gave birth to twins in October.)

Few understand the feeling of public shame better than Taurasi, who was 27 when she was arrested and charged in Phoenix in 2009 with extreme drunken driving and speeding. That summer, the Mercury suspended her two games without pay, and a Google search still pulls up thousands of headlines from the incident.

Other than this, and the fact that they're both in Russia to supplement their WNBA salaries, the two seem to have little in common. They're different heights, different ages, different colors. They're from very different places and have different sensibilities about almost everything, from diet to use of social media. And yet, the glaring space between them is what seems to make this whole thing work. Griner is an athlete struggling to come of age, wanting advice and guidance from someone with plenty to offer, which Taurasi does in spades.

But a word of advice: Don't call Taurasi a mentor.

Every winter, half of the WNBA's players flock overseas in search of a paycheck that dwarfs the one they get from the WNBA, including stars like Diana Taurasi and Brittney Griner. And that fact only compounds the league's difficulty in marketing itself.Mike Stocker for ESPN

THE SERVER AT Truffaldino has just appeared at the side of the table, and Taurasi is doing her best to make the interaction smooth.

"Hey, mama," Taurasi says.

But the woman does not react to -- or perhaps has not understood -- the colloquial greeting and instead waits for the drink order.

"Can I have sparkling -- Perrier, sparkling water?" Taurasi says. "Bella gas? Da, spasibo, Pellegrino." (Spasibo means thank you.)

"And I'll have Earl Grey tea," says Griner, who is sitting next to Taurasi. "As you can see, Dee speaks all the Russian."

"No, I just go at it," she says.

"Dee speaks all the Russian," Griner repeats.

"I like to say 'Spasibo, mama' -- it's kind of, you know ..."

Griner interrupts: "It's putting some Dee flavor on it."

"I don't know nearly enough Russian as I should for having been here 10 years," Taurasi says. "It's f---ing hard."

“I don't have to talk to anybody over here. I don't have to see anybody. I don't have to answer my phone. And everybody is asleep half the time when I'm up. I can be disconnected when I'm over here.”

- Brittney Griner

The server reappears with the tea and sparkling water, placing both on the table.

"Spasibo, mama," Taurasi says.

The woman bristles.

"See, she didn't like that," Taurasi says. "She's like, 'You might get put in jail.'"

Griner is laughing; she covers her face with her extra-large palm, shaking her head. "Oh my god," she says.

Taurasi is joking, of course, though the joke is loaded. In the past three years, Russia has made international headlines for its strict anti-LGBT law, making the country a curious choice for Griner, who has long been open about her sexuality. But Russia's hostile climate, which elsewhere in the country has resulted in arrests, seems a world away from Griner, who is here to play ball, not make a human rights stand. As long as she doesn't run through Red Square waving a rainbow flag, nobody says a thing.

Griner will be in Russia for seven months before she needs to be back in Phoenix for the WNBA season in May. Between her apartment, the arena, the car and the mall, the former Baylor standout could be outdoors a total of only a few hours if she wants. (And she does.) The concept of walking is routinely rejected for numerous reasons: The driver knows the city best; it's deathly cold out; and walking is dangerous. Despite an average temperature of 3 degrees in January and yearly precipitation of 18 inches, Yekaterinburg has developed an interesting approach for removing snow. It often doesn't. And so by the middle of January, the snow has been pressed by the wheels of thousands of cars and millions of shoes, transforming the city's pavement into something else entirely: a skating rink.

The whole city of Yekaterinburg seems perpetually dark and gilded with ice -- appropriate, considering its history. Nicholas II of Russia, the country's final czar, was executed here in 1918, along with his wife and five children, by the Bolsheviks after the Russian Revolution. In 2003, the Russian Orthodox Church erected a beautiful chapel with golden domes, the Church on the Blood, in the exact location the family was shot. At this time of year, ice sculptures that look like brick line the entrance, and the inside of the cathedral still feels chilly, despite heat pouring from the vents. Neither Griner nor Taurasi has visited the Church on the Blood, a short walk from UMMC's arena, but friends and family often do when they want to get to know this eclectic city -- wooden buildings reminiscent of Siberia, classic structures in bright pastels, modern skyscrapers, hip coffee spots, kitschy shops.

For Griner, and for Taurasi when she was younger, playing in Russia is a "life experience" -- a lesson in how to handle change, challenge and cultural differences. And perhaps nothing defines the yearlong existence of WNBA players more than those hurdles. As soon as they leave college, they exist in a perpetual state of motion. For five months, they live in the U.S., playing during the summer (a season few associate with hoops), making an average salary of $76,500. (Low-level rookies make less than $40,000, the very best players about $109,500.) That's a decent, but not overwhelming, amount of money for a professional athlete, and because the rest of the year is wide open, about half the WNBA players go overseas for a second paycheck, from Italy to Turkey to Russia. They are like modern-day nomads: Have jumper, will travel.

Of course, the top women's basketball stars have been playing overseas for more than 30 years -- well before the start of the WNBA. But when the league, backed by the NBA, started 20 years ago, some believed female players had finally found a permanent home. It hasn't worked out that way, for complicated reasons.

Griner has a driver to take her from her apartment to practice, the mall, anywhere she wants to go, so she can spend as little time as possible in the freezing outdoors. Mike Stocker for ESPN

This is Griner's first season in Russia after playing the previous two winters in China. Taurasi has played all over Europe: four seasons with Spartak Moscow; one with Fenerbahce Istanbul; one with Galatasaray Medical Park (also in Turkey); and here since 2012. Her travels have exposed her to the complicated nature of the women's basketball business model overseas. Some teams, such as Galatasaray, are part of a larger club structure that includes a lucrative soccer team. This would be like if the Dallas Cowboys, in an effort to expand their brand, operated volleyball and basketball teams. Other teams, mostly just in Russia, are funded by one rich owner who happens to enjoy women's hoops. Dozens of teams are funded in part by local governments, while other clubs, such as the one Taurasi and Griner now play for, are backed by a huge corporation. (UMMC is the second-largest copper producer in Russia and operates mines across Europe.)

To be clear, UMMC has not developed some winning algorithm for women's hoops popularity; tickets on the floor and in the lower bowl are just a few bucks, and tickets in the upper bowl are free. Some who attend the games truly enjoy women's hoops, but most just appreciate the possibility of free entertainment in a heated arena in the dead of winter.

In essence, the team is a form of advertising -- one that UMMC pays big bucks for. Griner will make a little less than $1 million this season, while Taurasi will make around $1.5 million. The former UConn star made headlines last spring when she decided to accept UMMC's annual offer, rumored to be more than $200,000, to not play the 2015 WNBA season. Her decision was a black eye for the WNBA, demonstrating that the league isn't the top priority for its marquee players. "It's all about right here," says Todd Troxel, an assistant for both UMMC and the Phoenix Mercury. "This is the big paycheck -- for all of us. We all love Phoenix, but ultimately it's all about here."

And so Taurasi and Griner are in Yekaterinburg, more than 5,000 miles from the U.S. and equally far from the daily sports media cycle. Out of sight, out of mind. Essentially, the WNBA and its players must attempt to reintroduce themselves to casual fans -- every single season.

Mike Stocker for ESPN

Mike Stocker for ESPN (2)

TAURASI TAKES A sip of water.

"When I got my DUI, I didn't want to go anywhere," she says. "I didn't want to do anything. I spent all night at the gym. For a month I was like that. Eventually, I was like, 'I can't do this the whole time.' So one day I was like, 'I messed up, I made a huge mistake.'"

Taurasi pauses and glances at Griner. "I'm not saying you made a mistake."

She continues: "I told myself, 'You know what, I'm just going to own up to it; I'm going to do what I have to do and then get over it.' And after that, little by little, I started feeling better. And it was my biggest lesson for my life. I was so embarrassed. And also, we live for basketball and I was suspended for two games. That was, 'Oh, man, can I pay a fine? You can take my whole WNBA salary. Can I just play?' But that was the thing I learned: You can't put your life in someone else's hands."

The server reappears, notepad in hand. Griner orders the lasagna Bolognese, which she says she has eaten almost every day she's been here. Taurasi orders a green salad and grains. She has recently cut out meat and dairy from her already strict diet. She used to love lattes and flat whites but gradually changed to black coffee.

"I think my progression started with no-sugaring coffee, and then I went no milk in coffee and I was like, 'I like coffee, but I like the coffee part of coffee,'" she says.

Technically, Taurasi is simply talking about her morning beverage, but the insight speaks to her deliberate decision-making process. Meanwhile, Griner is looking back on the past few months and wondering about her decisions. Perhaps that's all maturity actually is: having reason behind choices, being able to explain a certain decision.

"I feel better without meat and dairy," Taurasi continues. "Plus, I'm getting old, so if it can prolong my career by eating a little better ..."

"Yeah, we gotta take care of Granny over here," Griner says.

"I'm getting older, I know it."

"She can't retire until I retire," Griner says. "She can't go anywhere. I gotta have Dee around; I can't let Dee go nowhere."

Taurasi laughs, then says, "Every day is a challenge. You're like, 'Am I going to feel good today?' There are some days when you physically just can't warm up your body."

Griner rolls her eyes. "People would kill to have her f---ing bad day."

"Part of the reason these women are able to go overseas is the reputation and experience they get because of the WNBA," says Lisa Borders, the league's new president. "We're very happy they have that opportunity." Mike Stocker for ESPN

Taurasi, grinning, says, "I mean, it's what we do, BG. This is what we do. Some people are like" -- she shifts her voice into a Valley Girl accent -- "'I don't want to just be a basketball player.'"

The food comes and she picks up her fork. "Well, guess what: I just want to be a basketball player."

"I have no problem with that," says Griner, taking a bite of her lasagna.

"I just want to be a basketball player," Taurasi repeats, shrugging. "After BG's rookie season, she knew: I have to put the time in. No matter what's happening around you, no matter what you want to do with your life, social life, whatever, you make sure you take care of this because it's the only reason you're getting this other stuff. And that's where I think Twitter and Instagram and all that have people going crazy."

"F--- Facebook," Taurasi adds. "I'm so glad I'm not on social; I feel so relieved. I mean, has it affected my contracts? I know for a fact that it has. I know a couple of renegotiations they were like, 'Well, we need you to get to 10,000 followers.' It's like, 'I've won f---ing three gold medals. Are we really talking about Twitter followers right now?'"

"Dee is the damn best," Griner says. "She should be on every damn poster."

"But BG should be on posters right now," Taurasi says, then looks at Griner. "I mean, you should want to be on posters now. That's part of your selfish, young grind. Now I don't even know half the players in the WNBA. I just don't care."

“I always hear Dee when she speaks. I learned my lesson to listen.”

- Brittney Griner

Of course, the bigger problem is not whether Taurasi cares who's playing in the WNBA but that too few people -- anywhere -- care at all. Most female players learn the hard way that their popularity will never be higher than during college, especially if they play on a championship team, as did both Griner and Taurasi. At first blush, this lack of mainstream, recognizable WNBA stars seems like a marketing problem, and to some extent it is.

The sports media machine runs on trade rumors, free agency, rivalries, internal disputes, locker room controversy, bad guys and good guys. And over the years, the WNBA has been conservative -- burying stories that could have moved the needle, simply because it didn't want to air its dirty laundry.

Yet adopting a more transparent view of players and the league's inner workings raises tricky questions for the future. Is controversy good or bad for the WNBA? How will people feel when female athletes become multidimensional and complicated instead of just the "role models" we've always been force-fed? Taurasi and Griner are two of the best players in the league, but that's not solely why they're more relevant than other players. You could also argue that certain headlines -- Griner's domestic violence arrest, Taurasi's candor on league issues -- have raised their visibility in a way their play never could.

Mike Stocker for ESPN

Mike Stocker for ESPN

Mike Stocker for ESPN (3)

TAURASI PUTS DOWN her fork and pauses before speaking. "It's funny, when you're younger, you start with your family and then little by little your circle gets bigger. And now that I'm in my 30s, the opposite is happening. That circle is getting smaller and smaller. I think I text like three people in my life, and my mom and sister are two of them. But I don't feel as cloudy, because I'm not trying to please numerous people."

Griner tilts her head toward Taurasi. "It's funny you said that about texting people because my phone, my inbox has so many different people that I'm just talking to, just texting. And a couple days back, I was kind of looking and I was like, 'I couldn't tell you why I'm talking to half these people.' So I started cleaning house. I was like, 'Nope, nope.' Now when I open up my app, I have six little people in there I communicate with. Because I want to -- I actually want to. I'm not just responding because they hit me up."

"I realize now that not everybody should know what I'm doing 24/7," Griner says. "That's different for me." Mike Stocker for ESPN

"You're so worried about some s--- that's happening a world away. How about you make what's around you good?" Taurasi says.

Griner is smiling. "I realize now that not everybody should know what I'm doing 24/7," Griner says. "That's different for me. Yeah, I still use social media and I probably always will -- I love it. But as far as what I want to put out, no, they're not going to know every little thing anymore.

"I always hear Dee when she speaks. I always listen. I learned my lesson to listen."

So yeah, Diana Taurasi, The Mentor.

"No, not at all." Taurasi drops her fork, then leans back in her chair.

"Wait, what?" Griner turns. "You don't think you are?"

"I feel like if you have to make a concerted effort to mentor, you really don't give a s--- about that person," Taurasi says. "It's about you and how mentoring makes you feel. BG is my good friend and I have casual conversations of things I've been through, or someone else has, and you take what you take from it."

"And that's what I love," Griner says. "We're just talking, it's not formal. Just two hoopers talking."

"Everyone is like, 'What have you taught her?'" Taurasi says. "Nothing. She's learned everything herself. The only way you learn things is by going through things yourself. I'm pretty sure, up until the moment I got behind the wheel drunk, I'd heard 'Don't drink and drive' a million times. At some point, you have to make up your own mind about who you want to be, about why you're making the decisions you make."

Taurasi takes out her wallet and places a credit card on the end of the table.

"When you make decisions and you know why you're making them, you take the power back," she says. "You're making decisions that you want to make. The influencers, the people around you, the enablers or whoever, they don't have the power anymore. And maybe at the time, you didn't think they did, but they did. Oh, they did."

A minute later, Taurasi signs the bill. The two players stand and walk to the coat check. The restaurant's dark, intimate vibe is shattered at the front as the bright, artificial light of the mall cascades into the space.

Taurasi excuses herself to the bathroom while Griner hands the attendant their numbers. A second later, the coats appear. Griner pulls on hers, and when Taurasi returns, Griner holds open the coat as her teammate slips her arms into the sleeves.

"Now that's full service," Taurasi says.