|

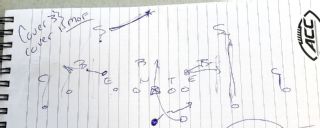

Traditional power run teams have decreased over the past decade, but rushing numbers have gone up. Sound counterintuitive? Maybe at first. But there is a simple explanation. "That's easy," Pitt head coach Pat Narduzzi said recently. "It's the spread offense." An offense that is more known for dual-threat quarterbacks and dynamic receivers is actually producing more prolific backs than ever. In each of the past three seasons, eight players have gone over 1,700 yards -- more than any stretch dating back to 2000, when the spread started gaining serious traction nationally. In the past two seasons, three running backs have crossed over 2,000 yards rushing -- including Tevin Coleman, out of a spread offense at Indiana. With 2015 being dubbed by some as the "Year of the Running Back," those numbers stand to grow higher. Five of the eight backs with more than 1,700 yards last year return, along with a slew of other outstanding players -- from Nick Chubb at Georgia to Paul Perkins at UCLA to Royce Freeman at Oregon. "We saw it. The more teams would spread and look to run -- not just to throw out of the spread -- there would be more explosive plays and more 1,000-yard rushers," Arizona coach Rich Rodriguez said. "We use it a lot in recruiting: 'Hey, you don't have to go to an I-formation team to get rushing yards. You can get as many or more playing in our style of offense than anything else.'" Rodriguez would know. Since he took his first head-coaching job at West Virginia in 2001, Rodriguez has coached five 1,700-yard players -- more than any other head coach. Over the same time frame, Oregon has produced four rushers with more than 1,700 yards. So the question to answer: Why has the spread opened up the run? When Rodriguez first started implementing the spread as an assistant 27 years ago, it was with throwing more in mind. But as the offense evolved, he found himself spreading more to run. The reason? A simple numbers game. "We felt you had to have less good blocks to have a successful run than if you put everybody in there tight," Rodriguez explained. "If we got two or three blocks at the point of attack, and the rest of the guys get run over slowly, we've got a chance -- as opposed to having to make five or six blocks. So that was our reasoning behind spreading to run. And having the quarterback with a threat to run makes defenses play all 11 guys instead of playing 11 on 10." Spreading the offense meant spreading the defense too, creating bigger seams and wide-open running lanes as defenses guessed whether the quarterback would run it, throw it or dish it to the backs.  Since 2004, 30 teams have had multiple 1,000-yard rushers. Eighteen have featured 1,000-yard quarterbacks; 16 teams with multiple 1,000-yard rushers played in a spread-type offense, including Oregon (2008), Auburn (2010, 2013) and Ohio State (2013). Defenses have been struggling to catch up. Over the past three seasons, running backs have averaged 5.1 yards per carry -- higher than any point since 2004. According to ESPN Stats & Information, teams faced an average of 6.8 defenders in the box last season, a number that has been slowly dropping since the average was 7.0 in 2011. Fewer men crowding the box means some teams are playing their linebackers outside. Others put one player in the middle of the field to try to combat all the different options the spread presents. Narduzzi, one of the top defensive minds in the game, remains old school in his approach -- no matter the offense. "That's a nice safety thing, but they've got 11 and you've got 10," Narduzzi said. "We run Cover 4 -- that guy never goes to the middle of the field. Now it's at least 11-on-11. We're trying to keep the middle of the field open, which maybe creates some other problems. But my philosophy has always been to stop the run. We're going to let Baylor throw the ball out there for 600 yards but they're going to rush for minus-20 yards. We're very risky in what we do, so it's high risk, high reward, but it's been very effective for us." Traditional power run teams might be dwindling, but some coaches believe they have benefited from the spread too. With more defensive schemes predicated on slowing down the spread, players are not accustomed to playing downhill, power run teams. Virginia assistant Chris Beatty worked at Wisconsin last year and watched Melvin Gordon run for 2,587 yards -- the second-highest total in NCAA history. Gordon is a rare talent in his own right, but defenses not only struggled to tackle him, they struggled to defend the right gaps. "It's harder and harder on defenses, and I think an advantage for us at Wisconsin was everybody's geared to stop the spread now," Beatty said. "We were one of a handful of teams that runs a pro-style offense, so it creates an issue personnel-wise for defenses -- how do they want to be? For us with Melvin Gordon, it was hard for people to match up." Boston College running back Andre Williams went over 2,000 yards in 2013 -- the first player to hit the mark in five years. He did it on a team that emphasized the power run game. His head coach, Steve Addazio, learned spread principles under Urban Meyer at Florida. But without a running quarterback, Addazio knew he had to rely on Williams to set the tone. But neither Addazio nor Williams believes defenses were caught off guard because BC ran a less common offensive scheme. "At the end of the day, you're trying to put the ball in the hands of the best player on your team," Addazio said. "Andre Williams was that for us that year. My experience with the spread was your quarterback ran. That was the way to get rid of the extra hat. With Andre, we had nine-man boxes so it had a lot to do with the quality of the front and the quality of the back." Added Williams: "I don't think we were fooling anybody. They knew what was coming when they were playing BC. Whether or not they were geared for it based on the prevailing offense of the day, I'm not sure. We knew we were good at what we were doing, and we told ourselves that we weren't going to let anybody stop us." The no-huddle philosophy that accompanies the spread offense also has helped push up rushing numbers, as more and more teams run more and more plays. So have the added games to the schedule. Also remember, the NCAA did not start counting bowl stats until 2002. Ezekiel Elliott ran for 1,878 yards last season in 15 games at Ohio State. In fact, of the eight players with more than 1,700 yards last season, only Coleman played in 12 games. For argument's sake, let's use the old standard -- a 1,000-yard season. Last year, 53 players went over that mark. Compare that to the year 2000, when 40 players hit 1,000, not counting bowl games. Only two backs went over 1,700 yards that year. LaDainian Tomlinson at TCU (2,158 yards) played in 11 games; Damien Anderson at Northwestern had 1,914 yards in the regular season, but went over 2,000 if bowl stats are included. Indiana coach Kevin Wilson was offensive coordinator at Northwestern that year. He decided to bring the spread to the Wildcats after learning it from Rodriguez, believing that would be the best way to make his team competitive in the 3-yards-and-a-cloud-of-dust Big Ten. As an offensive coordinator and head coach, Wilson has mentored four backs to go over 1,700 yards since 2000, plus two backs to go over 1,000 yards in the same season (DeMarco Murray and Chris Brown at Oklahoma in 2008). "Initially, I think people believed the spread was cute," Wilson said. "But sometimes football is like going to a museum and looking at a piece of art. Different people look at different pictures and see different things. As people started spreading, it's neat looking at some of the ideas guys come up with. A lot of them aren't new ideas. It's the old ideas with some cute little window dressings. The beauty of the last couple years is the way the ball's been spread. But there also have been some decent lines and some really good players as much as anything." Nobody will argue that point. There is as fine a collection of running backs returning to college football as there has been in quite some time. But it is worth noting that schemes have opened up many more possibilities. "It's going to become where 1,500 yards used to be the benchmark," Beatty said. "There's going to be a handful of guys that threaten 2,000 every year for the foreseeable future."

|